Uarsciek was an Adua-class coastal submarine (TN 600 series, Bernardis type) with a displacement of 698 tons on the surface, 866 tons submerged. Together with the twin boats Dagabur, Dessiè and Uebi Scebeli, it was powered by Tosi diesel engines, instead of FIAT or CRDA like the other submarines of the class. The electric motors were Marelli, as for most of the other “Adua” (except for the group built by CRDA).

Uarsciek a few moments before its launch, on September 19th, 1937; in the background you can see a Mameli-class submarine. Note the name still written on the hull in the original version of “Uarsheich”

(from “Sommergibili Italiani” by Alessandro Turrini and Ottorino Ottone Miozzi, USMM, Rome 1999)

During the conflict she carried out 28 war missions (19 patrols, 1 transport and 8 transfers), operating from the bases of Taranto, Leros, Augusta and Messina, covering a total of 19,685 miles on the surface and 3,926 submerged. Initially intended (1940-1941) for offensive patrols along the main British shipping lines in the central and eastern Mediterranean, in 1942 it was instead used in the western Mediterranean, to contrast British air and naval operations.

The launch of the submarine Uarsciek in Taranto on September 19th, 1937

Brief and partial chronology

December 2nd, 1936

Uarsciek was laid out in the Franco Tosi shipyards in Taranto.

September 19th, 1937

Uarsciek (construction number 68) was launched at the Franco Tosi shipyard in Taranto, and the Archbishop of Taranto (TN Monsignor Ferdinando Bernardi) blesses the new unit before the launch.

Uarsciek a few moments before its launch, on September 19, 1937; in the background you can see a Mameli-class submarine. Note the name still written on the hull in the original version of “Uarsheich” (from “Italian Submarines” by Alessandro Turrini and Ottorino Ottone Miozzi, USMM, Rome 1999, via www.betasom.it and via Marcello Risolo)

December 4th, 1937

The boat entered service as ‘Uarsheich’, the seventh unit of the Adua class to be completed. Initially assigned to Taranto as part of the IV Submarine Group.

March 15th, 1938

The name was changed to Uarsciek, a version considered more faithful to the original name of the Somali village after which the submarine was named (provision made official by royal decree no. 393 of March 31st, 1938).

June 1938

The boat made a cruise in the Aegean Sea and was stationed in Leros.

1939

Stationed in Tobruk, Uarsciek made a cruise along the coast of Libya.

June 9th, 1940

On the eve of Italy’s entry into the war, Uarsciek was sent to lie in wait off the Greek-Albanian coast, along with the submarines Anfitrite, Antonio Sciesa and Balilla, forming a barrage of submarines along the coasts of Greece, Albania and Yugoslavia. Uarsciek, in particular, was sent to lie in wait south of Kefalonia, in order to keep under surveillance the accesses to the roadstead of Argostoli and the Gulf of Patras. At the end of the mission, the boat reached Taranto without having made any noteworthy sightings.

June 10th, 1940

Upon Italy’s entry into the World War II, Uarsciek (Lieutenant Carlo Zanchi) was part of the XLVI Submarine Squadron (IV Grupsom of Taranto), along with the twin boats Dagabur, Dessiè and Uebi Scebeli.

September 6th, 1940

Uarsciek left Taranto under the command of Lieutenant Carlo Zanchi, to carry out a patrol off the coast of Egypt. Along with Uarsciek, a second submarine, the Ondina, also took to the sea. The two boats, which set sail within four minutes of each other, and were both bound for North African waters, travelled together.

September 7th, 1940

Uarsciek was accidentally attacked with depth charges by the destroyer Granatiere, who had mistaken it for an enemy submarine. The attack did not cause damages, but it caused the boat to lag slightly behind schedule.

September 12th, 1940

At three o’clock in the morning (according to another source 3.27) the British submarine H.M.S. Proteus (Lieutenant Commander Randall Thomas Gordon-Duff) sighted “suspicious lights” in position 32°21′ N and 24°39′ E, on a 150° bearing, and approached to see what it was. After a while he sighted an Italian submarine surfaced and began an attack maneuver, but the latter dived before H.M.S. Proteus could launch. The H.M.S. Proteus then dove in turn and descended to 30 meters, attempting to conduct a submerged attack with the help of the sonar, but the Italian submarine passes on its vertical, which thwarted this intention.

At 4:16 AM, the British boat sighted another Italian submarine (40 miles east-northeast of Tobruk), pulled over toward it and immediately launched a torpedo from 1,370 meters, submerging immediately after. The torpedo missed its target, probably passing aft (it was heard exploding at the end of its run ten minutes later). It is probable that the target of this attack was Uarsciek (more likely, since due to the delay it had probably remained further behind the Ondina), or another Italian submarine sailing from Taranto to North African waters. The Ondina (which had departed from Taranto with an interval of only four minutes with respect to Uarsciek, and with the order to conduct an ambush in North African waters). None of the boats appeared to have noticed the attacks.

Uarsciek then reaches the area assigned for the patrol and began its mission regularly.

September 19th, 1940

On this date, according to a source of uncertain reliability, Uarsciek unsuccessfully attacked two British destroyers off the coast of Tobruk, along with the submarines Ruggiero Settimo and Ondina, but no confirmation of this events has been found.

September 21st, 1940

Following mercury vapor poisoning of several crewmen, caused by an accident that occurred on board, Commander Zanchi aborted mission and the return to Taranto and decided instead to reach the nearest port Benghazi, where the entire crew disembarks and were hospitalized (including Zanchi himself, later decorated with the Silver Medal for Military Valor: “Commander of a submarine, during a war mission, due to an accident that occurred to the unit, he was struck by serious intoxication. For more than five days, he overcame the sufferings caused by the disease with great fortitude, and by his example he encouraged the crew, who were also seriously intoxicated, and succeeded in carrying out his mission. As soon as he arrived in port, he had to be hospitalized. An example of dedication to duty, a high spirit of sacrifice“).

One of the intoxicated, nineteen-year-old Ermanno Tironi from Bergamo, died on October 5th in the Benghazi hospital. A Bronze Medal for Military Valor would be awarded in his memory, with the motivation “Embarked on a submarine, during a war mission, due to an accident that occurred to the unit he was struck by serious intoxication. Despite the suffering caused by the disease, he continued to carry out his service serenely with a high sense of duty for over five days, succeeding in setting an example to the other soldiers who were also seriously intoxicated. As soon as he arrived in port, he had to be hospitalized, where he died of aggravated intoxication. (Central Mediterranean, 7-22 September 1940)“.

The news of Ermanno Tironi’s death on the “Rivista di Bergamo”

(From Rinaldo Monella)

Other members of the intoxicated crew would have serious health problems for the rest of their lives, such as the sailor Luigi Bolognesi, who will not even be able to obtain compensation for what happened to him.

Uarsciek was then summarily put back into service with the means available on site and transferred to Italy under the command of Lieutenant Commander Mario Resio, assisted by Lieutenant Marcello Bertini, Lieutenant Lorenzo Coniglione, chief electrician first class Angelo Pilon and chief mechanic first class Catello Primo Gargiulo. They were in turn intoxicated by mercury during this transfer, and decorated for their work with the War Cross of Military Valor (for Resio, the motivation was: “He organized and directed at a naval base the reclamation and re-efficiency works of a submarine polluted by mercury vapors, overcoming with serene firmness continuous and harsh difficulties of a technical nature worsened by frequent enemy aerial bombardments. Once this task was completed, he managed to transfer the unit to his Command in a national base, although he was struck during the mission by mercurial gas poisoning”; for the others, “He participated with enthusiasm and a keen sense of duty at the naval base of the A. .ai reclamation and rehabilitation of a submarine polluted by mercury vapour, despite technical difficulties and continuous enemy bombing; embarked on the unit, contributed to its transfer to a national base, during which he was struck by mercurial gas poisoning”).

November 11th through 12th, 1940

Uarsciek was in Taranto, moored at the submarine quay in Mar Piccolo (along with numerous other boats of the IV Submarine Group: Pietro Micca, Ambra, Anfitrite, Malachite, Naiade, Nereide, Ondina, Sirena, Atropo and Zoea, as well as at Dagabur, Serpente and Smeraldo of the X Grupsom, Giovanni Da Procida of III Grupsom and Ciro Menotti of VIII Grupsom), when the base was attacked by British torpedo bombers that sank the battleship Conte di Cavour and seriously damaged two others, Littorio and Duilio (the famous “night of Taranto”). The submarines are not affected by the attack.

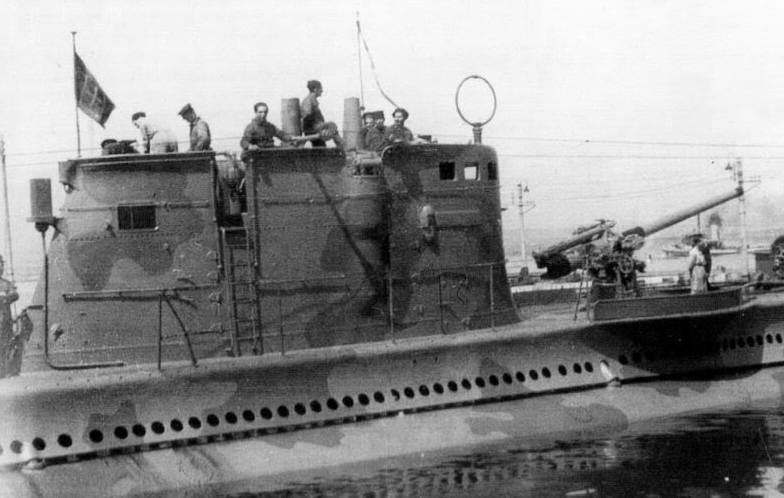

Uarsciek in1940

(Erminio Bagnasco)

January 1st, 1941

Lieutenant Alberto Campanella took command of Uarsciek and held it for the next six months.

January 31st through -February 12th, 1941

Uarsciek carried out a patrol in the Otranto Channel to protect the traffic between Italy and Albania, without sighting enemy ships.

March 6th through 18th, 1941

Another patrol south of the Otranto Channel, off the Ionian Islands, to protect convoys sailing between Italy and Albania.

April 21st thought 30th, 1941

Third and final protective patrol near the Otranto Channel to defend convoys between Italy and Albania.

May 19th through June 2nd, 1941

The boat was part of a group of submarines (the others were Fisalia, Topazio, Malachite, Adua, Tricheco, Squalo, Smeraldo, Dessiè and Sirena) deployed in the waters between Crete, Alexandria and Sollum, in support of the German invasion of Crete. Uarsciek, in particular, patroled the Cyrenaic-Egyptian waters (according to Aldo Cocchia’s memoirs, in this mission Uarsciek attacked a British cruiser south of Crete, believing it to have torpedoed it).

June 17th, 1941

Lieutenant Alberto Campanella leaves the command of Uarsciek, passing to the minelayer submarine Zoea. He was replaced by Lieutenant Raffaello Allegri, who would command Uarsciek for a year.

June 1941

Patrol between Tobruk and Alexandria.

July 19th through 31st, 1941

Uarsciek was sent on patrol off Alexandria, Egypt, along with the submarines Squalo and Axum.

July 29th, 1941

At 4:30 PM, Uarsciek (Lieutenant Raffaello Allegri), on a mission in the eastern Mediterranean off the Egyptian coast, was attacked north of Ras Haleima (in position 31°38′ N and 25°54′ E) by a Bristol Blenheim bomber of the 203rd Squadron of the Royal Air Force, aircraft “Y”/Z6445 piloted by Lieutenant Coates, which dropped four bombs which fell into the sea about 150 meters aft of the submarine. Uarsciek reacted with machine-gun fire. At 5:45 PM, the submarine suffered a second attack by another Blenheim IV of the 203rd Squadron, aircraft “N”/Z6431 piloted by Sergeant E. Langston, which dropped six bombs that fell into the sea about 200 meters forward of Uarsciek. Once again, the submarine responds with machine gun fire. Langston’s plane, on its return to its base near Marsa Matruh, would be irreparably damaged following the failure of the landing gear, although the crew emerged unscathed. According to British sources, however, the damage was not caused by Uarsciek’s gunfire, which did not hit the plane (except for the book “The Bristol Blenheim” by Graham Warner, which instead states that the plane was damaged by the submarine’s fire).

August 11th, 1941

At 18.25 Uarsciek, while returning from Bardia, was strafed by an unidentified aircraft in position 34°05′ N and 22°20′ E. The under-helmsman Salvatore Bortone, from Diso, was seriously wounded (he was later decorated with the War Cross for Military Valor, with the motivation: “Embarked on a submarine subjected to violent air attack, although wounded he continued to carry out his task as a machine gun supplier with serene firmness, demonstrating a high sense of duty”). At some point, however, the attacking aircraft makes the German Air Corps recognition signal and left. It was, therefore, a “friendly fire” incident: a Luftwaffe plane had mistaken Uarsciek for an enemy submarine.

October 15th, 1941

The boat was sent to lie in wait off the coast of Cyrenaica.

1941

Uarsciek underwent a period of maintenance work in the Pula shipyards, after which it was deployed to Messina and then to Cagliari, from where it operated against the British ships that tried to supply Malta from Gibraltar.

Uarsciek moored in Taranto in December 1941

(from “Sommergibili in guerra” by Achille Rastelli and Erminio Bagnasco)

March 1942

Sent east of Malta along with other submarines (Corallo, Admiral Millo, Onice and Veniero), to protect operation “V. 5” (March 7th thought 9th). The latter provides for the dispatch to Tripoli of three convoys from Brindisi, Messina and Naples, with a total of four modern motor ships (Nino Bixio, Gino Allegri, Reginaldo Giuliani and Monreale) escorted by the destroyers Bersagliere, Fuciliere, Ugolino Vivaldi, Antonio Pigafetta and Antonio Da Noli and by the torpedo boats Castore and Arethusa, as well as the indirect escort of the VII Cruiser Division (light cruisers Eugenio di Savoia, Raimondo Montecuccoli and Giuseppe Garibaldi) and the destroyers Alfredo Oriani, Ascari, Aviere, Geniere and Scirocco. Another convoy of modern motor ships (Unione, Lerici, Ravello and the tanker Giulio Giordani, escorted by the torpedo boats Cigno and Procione and the destroyer Strale which will then be joined by Pigafetta and Scirocco) returning from Libya to Italy, will also be at sea for the same operation, which also benefited from the indirect escort of the VII Division.

The intervention of submarines would not be necessary; the operation ended without losses, despite repeated air attacks (while a British light formation, which had gone out to sea to attack the convoy, suffered the loss of the light cruiser Naiad, sunk by the German submarine U 565).

April 1942

At the end of the the month, Uarsciek patrolled the waters off Cyrenaica.

May 1942

Patrol in the waters of the Strait of Sicily and Tunisia.

Mid-June 1942

Uarsciek (Lieutenant Commander Raffaello Allegri) was sent to lie in wait in the Gulf of Philippeville during the air-naval battle of Mid-June, to counter the British operation “Harpoon”, consisting of sending a heavily escorted convoy from Gibraltar to Malta.

After an earlier supply operation in Malta in March 1942 (which resulted in the inconclusive naval clash of the Second Battle of Sirte) ended with the loss of 24,000 of the 25,000 tons of supplies sent by air, Malta’s situation became very critical: food rationing had to be introduced in May and the calories supplied daily to the garrison were halved (from 4,000 to 2,000) while for the civilian population the reduction was even more marked (1,500 calories).

The British commands, therefore, planned for mid-June a double resupply operation, divided into two sub-operations: “Harpoon”, with a convoy departing from Gibraltar, and “Vigorous”, departing from Alexandria. The latter consists of sending a convoy of eleven merchant ships, escorted by seven light cruisers, an anti-aircraft cruiser, 26 destroyers, 4 corvettes, 2 minesweepers, 4 motor torpedo boats and 2 rescue ships, in addition to the old target ship Centurion, a former battleship disguised again, for the occasion, as a battleship in an attempt – failed – to make Italian reconnaissance believe that the escort also includes a battleship. The bulk of the Italian battle fleet, under the command of Admiral Angelo Iachino, took to the sea against “Vigorous”.

The convoy of Operation “Harpoon”, which departed from Gibraltar on June 12th, consisted of 6 merchant ships: the British steamers Burdwan, Orari and Troilus, the Dutch motor ship Tanimbar, the US motor ship Chant and the brand new US tanker Kentucky, which carry a total of 43,000 tons of supplies. The direct escort of the convoy, designated Force X, consists of the anti-aircraft cruiser H.M.S. Cairo (Captain Cecil Campbell Hardy, commander of Force X), the destroyers H.M.S. Bedouin, H.M.S. Marne, H.M.S. Matchless, H.M.S. Ithuriel and H.M.S. Partridge (belonging to the 11th Destroyer Flotilla), the escort destroyers (Hunt class) H.M.S. Blankney, H.M.S. Badsworth, H.M.S. Middleton and Kujawiak (belonging to the 19th Destroyer Flotilla), the minesweepers H.M.S. Hebe, H.M.S. Speedy, H.M.S. Hythe and H.M.S. Rye and 6 “motor launches” used for dredging (ML-121, ML-134, ML-135, ML-168, ML-459, ML-462). All the units of the escort were British with the exception of the Kujawiak, which was Polish.

In addition to the direct escort, in the first leg of the navigation (from Gibraltar to just before the entrance to the Strait of Sicily) the convoy was also accompanied by a powerful covering force, Force W of Vice Admiral Alban Curteis: it was composed of the battleship H.M.S. Malaya, the aircraft carriers H.M.S. Eagle and H.M.S. Argus, the light cruisers H.M.S. Kenya (Curteis’ flagship), H.M.S. Charybdis and H.M.S. Liverpool and the destroyers H.M.S. Onslow, H.M.S. Icarus, H.M.S. Escapade, H.M.S. Wishart, H.M.S. Antelope, H.M.S. Westcott, H.M.S. Wrestler and H.M.S. Vidette.

According to an article by Enrico Cernuschi, Supermarina was alerted by the Navy’s Information Department as early as the morning of June 11th, following decryptions of British communications and direction finding from which it emerges that a British convoy bound for Malta was preparing to enter the Mediterranean from the Strait of Gibraltar. These were followed by reports from Italian observers stationed in Algeciras (near Gibraltar) and from Italian spies operating on Spanish fishing boats sailing in those waters. Finally, at one o’clock in the afternoon of June 12th, aerial reconnaissance dispelled all doubts.

According to the official history of the U.S.M.M., however, Supermarina received the first news of “Harpoon” at 7.55 AM on June 12th, when informants based in the Gibraltar area reported the departure from Gibraltar of a powerful naval squadron composed of H.M.S. Malaya, H.M.S. Eagle, H.M.S. Argus, at least three cruisers and several destroyers (Force W), heading east, as well as the passage through the strait, with the lights off, of numerous ships coming from the Atlantic.

The Italian Navy Command has correctly assumed that a large convoy from the Atlantic was therefore sailing from Gibraltar to Malta, an impression confirmed by the subsequent sightings of aerial reconnaissance (although the possibility that it was instead an operation directed against North Africa, Corsica, Sardinia or the Gulf of Genoa was not completely excluded, eventualities, however, considered unlikely). To counter this convoy, Supermarina developed a plan that included sending a large deployment of submarines to the western Mediterranean, the deployment of torpedo boats and MAS lurking in the Strait of Sicily, cooperation with the Regia Aeronautica so that the convoy would be heavily attacked by aircraft south of Sardinia, weakening its escort, and the dispatch of a light naval formation (the VII Division of Admiral Alberto Da Zara, with the cruisers Eugenio di Savoia and Raimondo Montecuccoli and two squadrons of destroyers), particularly suitable for combat in circumscribed and treacherous waters, to attack the convoy by surprise at dawn on the 15th.

A total of 16 boats were deployed in the central and central-western Mediterranean to counter “Harpoon”. The doctrine of the use of submarines has changed compared to the past. Now it was planned to use them en masse against ships or groups of ships sighted and reported by aircraft. Uarsciek, along with the submarines Giada, Acciaio and Otaria, formed a barrier north of the Algerian coast, in the waters between Cape Bougaroni and Cape Ferrat. Uarsciek and Giada were located at the western end of the weir. While in mid-August, two months later, this tactic was very successful, in mid-June the submarines did not reap any results.

June 13th, 1942

In the late evening, 90 miles north of Bougie and east of Algiers (in position 38°02′ N and 05°06′ E), Uarsciek sighted a British naval formation composed of numerous units proceeding eastwards in several columns: these are the forces engaged in Operation “Harpoon” (according to a source it would have been, more precisely, Force X, but this seems unlikely, since Force X did not include any aircraft carriers; Francesco Mattesini, on the other hand, speaks more generically of Force T, i.e. the complex of Forces W and X – not yet separated, at the time of the attack – which also included the aircraft carriers Eagle and Argus). Remaining on the surface, the Italian submarine approached to attack, and at 23:52 launched three torpedoes against the two largest silhouettes it could see. Not distinguishing superstructures, Commander Allegri believes that these are aircraft carriers.

Immediately after the launch, some escort units pull in the direction of Uarsciek, which is thus forced to disengage from diving without being able to verify the outcome of the launches. After 135 seconds from the launch, a loud explosion is heard on Uarsciek (according to other sources two or three would have been heard), which leads to believe that a torpedo was certainly landed, but in reality the torpedoes exploded prematurely; On the British side, in fact, the aircraft carrier Eagle felt two loud underwater explosions at 2.55 AM (for another source, the official British report states only that “at 1.42 AM the naval force was probably sighted and reported by a submarine”, and the explosions heard on board Uarsciek could be due to depth charges). After about twenty minutes, Uarsciek noticed that two British destroyers were stationed in its vicinity, one stationary and one moving slowly.

Italian informants in Gibraltar will later report that in this action Uarsciek probably damaged the fast minelayer Welshman (and Commander Allegri will be decorated with the Silver Medal for Military Valor, with the motivation “Commander of a submarine, on a war mission, he sighted an enemy naval formation at night, attacked it with a decisive aggressive spirit and high skill and, having passed the protection escort, It hit her with two torpedoes, inflicting severe damage. Subjected to violent hunting, with prompt maneuvering he managed to elude it, demonstrating during the mission serene daring and conspicuous military skills”), but this is incorrect information: neither the Welshman, nor any other British ship was hit by torpedoes.

June 14th, 1942

At 1:40 AM, when the attack was over, Uarsciek sent the enemy formation discover signal the. (Giorgio Giorgerini, in his book “Uomini sul fondo”, gives different times for this attack: the sighting of the British forces by Uarsciek took place at 1.40 AM on June 14th, and the launch of the torpedoes at 1.52 AM In addition, Giorgerini claims that the launch took place against two units of the escort. Francesco Mattesini, in one of his essays on the “Pedestal” operation, indicates 1.20 AM as the time of the torpedo launch).

The unsuccessful attack by Uarsciek is the first ever launched against the “Harpoon” convoy during the Battle of Mid-June. All attacks by Italian submarines in the course of the battle were equally unsuccessful. The convoy, on the other hand, suffered serious losses due to the joint action of the Italian-German planes and the VII Naval Division of Admiral Alberto Da Zara, to which were later added those caused by minefields. A total of four merchant ships and two destroyers sank, while several other units suffered serious damage. Of the 43,000 tons of supplies carried by the ships of “Harpoon”, only 15,000 reached Malta (while the convoy “Vigorous”, with its 50,000 tons of supply, would be forced to give up its mission and return to Alexandria).

June 15th, 1942

Around nine o’clock in the morning, northwest of Cape Bougaroni, Uarsciek sighted the British W Force (aircraft carriers H.M.S. Eagle and H.M.S. Argus, battleship H.M.S. Malaya, cruisers H.M.S. Kenya and H.M.S. Charybdis – a third cruiser, H.M.S. Liverpool, left the formation after being hit by Italian torpedo bombers –, destroyers H.M.S. Antelope, H.M.S. Icarus, H.M.S. Escapade, H.M.S. Onslow, H.M.S. Westcott, H.M.S. Wishart, H.M.S. Wrestler, and H.M.S. Vidette) sailing towards Gibraltar. This formation, in charge of covering the convoy in the first phase of the navigation, reversed course at the entrance to the Strait of Sicily, at 8.30 PM the previous evening, allowing the convoy to continue towards Malta with the direct escort of Force X (anti-aircraft cruiser H.M.S. Cairo, 9 destroyers, 4 destroyers and some smaller units), and was then returning to Gibraltar at 16 knots. Force W arrived without suffering further losses, despite unsuccessful attacks by the submarine Alagi and the Italian-German air force.

June 17th, 1942

At 2.45 PM, during the return navigation to Cagliari, Uarsciek was sighted in position 38°27′ N and 08°21′ E by the British submarine P 211 (later Safari, Commander Benjamin Bryant). The latter tried to approach and attack, but Uarsciek, continuing its course without realizing it, continued moving away and was soon too far away to hope for a hit it.

June 21st, 1942

Lieutenant Gaetano Arezzo della Targia took command of Uarsciek, alternating with Commander Allegri; he would be his last commander. Under his command, Uarsciek carried out seven missions in the central Mediterranean between June and December 1942.

Picture of Lieutenant Gaetano Arezzo della Targia

(TN Barons Arezzo della Targia where a noble family from Catania, Sicily)

End of June 1942

Uarsciek carries out a new mission in the Western Mediterranean.

August 4th, 1942

Uarsciek (under the command of Lieutenant Gaetano Arezzo della Targia, and with the captain of the Naval Engineers Arturo Cristini as chief engineer), was part of the VII Grupsom of Cagliari. It sailed from La Maddalena bound for a patrol sector located halfway between Menorca – Formentera and the coast of Algeria.

August 7th, 1942

Uarsciek reaches its field of operations.

August 10th, 1942

The boat received a telegram from the Submarine Squadron Command (Maricosom) alerting to the passage of the “Pedestal” convoy, which had already been announced by faint and indistinct noises picked up by Uarsciek hydrophones.

The Battle of Mid-August was about to begin: the largest air-naval clash ever fought in the Mediterranean would see the air and naval forces of the Axis – bombers, torpedo bombers, submarines, motor torpedo boats, with even an ephemeral offensive bet by two cruiser divisions – fiercely oppose the transfer of a large British convoy sailing from Gibraltar to Malta, with a supply shipment vital to prolonging the resistance of the besieged island.

The Italian and German submarines would play a leading role in this: their task was twofold: to attack the convoy directly and – since experience has shown that too often reconnaissance aircraft are intercepted and shot down by fighters embarked on aircraft carriers before they can carry out their task – to allow the commanders to have reliable information about the composition enemy formation, course and speed, which were essential for coordinating the action of the air and naval forces destined to attack the convoy, especially the air forces.

In fact, on August 10th, Supermarina ordered Uarsciek and the other submarines lurking in its area (Brin, Giada, Dagabur, Volframio, U 73 and U 331) to consider the reconnaissance and signalling of the enemy forces sighted as their primary task, and only an attack secondary.

The Battle of Mid-August was the consequence of the Royal Navy’s new attempt to supply Malta, besieged by Axis air and naval forces and exhausted after months of bombing and the partial or total failure of the refueling operations attempted in March (convoy “M.W. 10”, culminating in the second battle of Sirte) and June (operations “Harpoon” and “Vigorous”, culminating in the Battle of Mid-June). The new operation, called “Pedestal”, involves a single large convoy which, assembled in the United Kingdom (from where it departed on August 3rd, 1942), crossed the Strait of Gibraltar between August 9th and 10th, and then headed for Malta.

The convoy consisted of the cargo ships Almeria Lykes, Melbourne Star, Brisbane Star, Clan Ferguson, Dorset, Deucalion, Wairangi, Waimarama, Glenorchy, Port Chalmers, Empire Hope, Rochester Castle and Santa Elisa and a large tanker, the American Ohio; the direct escort (Force X, Rear Admiral Harold Burrough) counted on four light cruisers (H.M.S. Nigeria, H.M.S. Kenya, H.M.S. Cairo and H.M.S. Manchester) and twelve destroyers (H.M.S. Ashanti, H.M.S. Intrepid, H.M.S. Icarus, H.M.S. Foresight, H.M.S. Derwent, H.M.S. Fury, H.M.S. Bramham, H.M.S. Bicester, H.M.S. Wilton, H.M.S. Ledbury, H.M.S. Penn and H.M.S. Pathfinder, of the 6th Destroyer Flotilla), and also in the first half of the voyage, up to the entrance of the Strait of Sicily, the convoy was accompanied by a powerful heavy force (Force Z, Vice-Admiral Neville Syfret) consisting of four aircraft carriers (H.M.S. Eagle, H.M.S. Furious, H.M.S. Indomitable and H.M.S. Victorious), two battleships (H.M.S. Rodney and H.M.S. Nelson), three light cruisers (H.M.S. Sirius, H.M.S. Phoebe and H.M.S. Charybdis) and twelve destroyers (H.M.S. Laforey, H.M.S. Lightning, H.M.S. Lookout, H.M.S. Tartar, H.M.S. Quentin, H.M.S. Somali, H.M.S. Eskimo, H.M.S. Wishart, H.M.S. Zetland, H.M.S. Ithuriel, H.M.S. Antelope and H.M.S. Vantsittart, of the 19th Destroyer Flotilla).

For their part, the Italian commanders received the first news about a major operation being prepared by the British, which was to take place in the Western Mediterranean, in the early days of August. At 5 AM on August 9th, Supermarina was informed that a group of at least eight ships had passed north of Ceuta, heading east (it was British Force B). In the early hours of the morning of the following day, news came that between 00:30 and 2:00 AM on the 10th, a total of 39 ships crossed the Strait of Gibraltar bound for the Mediterranean, and that a few hours later a dozen British ships set sail from Gibraltar, including the anti-aircraft cruiser H.M.S. Cairo. On the morning of August 10th, therefore, on the basis of the information received thus far, Supermarina estimated that at least 57 British ships from Gibraltar were heading east. As these ships include a number of large steamers in convoy, it was rightly assumed that the object of the operation was to supply Malta. The convoy would be protected by a powerful heavy naval force, and the convoy will probably try to cross the Pantelleria area under cover of darkness. The convoy was expected to arrive at Cape Bon (Tunisia) in the afternoon of August 12th. There did not appear to be any signs of a second convoy sailing in the Eastern Mediterranean, unlike what happened in June. On the morning of the 12th, a German U-boat reported in those waters a formation of four light cruisers and 10 destroyers apparently heading towards Malta at 20 knots, but it was rightly judged that this was a diversionary action (and in fact it was so: the “M.G.3” operation, a secondary operation of “Pedestal”, in fact provided for the dispatch from Haifa and Port Said of a small convoy that had to pretend to be headed towards Malta in the attempt to divert Italian forces from the actual convoy).

The Italian and German commands therefore organized the fight against the British operation: aerial reconnaissance throughout the western Mediterranean basin; warning of submarines already lurking south of the Balearic Islands, dispatch of a second group of submarines south of Sardinia (where they had to arrive no later than dawn on the 12th), laying of new offensive minefields in the Strait of Sicily, dispatch of MAS and motor torpedo boats lurking south of Marettimo, off Cape Bon and if necessary also below Pantelleria.

While sailing in the western and central-western Mediterranean, the British convoy would be subjected to a series of submarine attacks. Once in the Strait of Sicily, it would be the turn of MAS and Italian and German motor torpedo boats (fifteen units in all, which will attack under cover of darkness). Throughout the crossing, moreover, the enemy ships will be continuously targeted by incessant attacks by bombers and torpedo bombers (in all, as many as 784 aircraft), both of the Regia Aeronautica and of the Luftwaffe. It is also planned the intervention (later aborted) of two cruiser divisions (the III and the VII) to finish what should remain of the convoy decimated by the previous air, underwater and insidious attacks.

Altogether, as many as 16 Italian submarines and 2 German U-boats contribute to the formation of a powerful submarine barrage in the western Mediterranean: seven of them, including Uarsciek (which was the westernmost of all; the others are the Italian Brin, Giada, Dagabur and Volframio and the German U 73 and U 205), were located in the waters between Algeria and the Balearic Islands. forming a sixty-mile-long barrier between the meridians 01°40′ E and 02°40′ E (i.e., north of Algiers and south of the channel between Mallorca and Ibiza), while the other eleven form a second group much further east, north of Tunisia.

At 11:20 PM, Uarsciek headed towards the center of the assigned ambush area, assuming a 160° course, which coincidentally happened to be perpendicular to the hydrophone survey carried out at 9:56 PM

August 11th, 1942

At 3.40 AM, Uarsciek, having entered the indicated area, dove to make a new hydrophonic listening; as predicted by Commander Arezzo, the hydrophones detect noises of turbines approaching in a large sector on 267° detection, force 4. At four o’clock the submarine emerged and after a few minutes began to move westwards, but without advancing at full strength: the captain intends to avoid generating a wake that would be too visible. Visibility was rather mediocre, which suggested that the sighting of enemy ships would take place at close range.

At 4.38 AM the aspiring midshipman Francesco Florio, on the lookout forward portside, announced the sighting of a dark silhouette for 340°-350°, at 3,200 meters. Upon observing it, the commander Arezzo della Targia immediately recognized it as an aircraft carrier, later identified as a U.S. unit of the Saratoga type.

It was the British H.M.S. Furious, headed south of the Balearic Islands to launch 39 Supermarine Spitfire fighters that would reinforce the decimated squadrons of Malta during “Pedestal”. This sub-operation was named ‘Bellows’. The inclusion of the old Furious in the operation was decided in the final stages of planning for “Pedestal”, after the commands of the Maltese Air Force asked to replenish their fighter squadrons, which have suffered serious losses in recent times (quantified at an average of 17 aircraft per week). The Chief of Staff of the Royal Air Force, Air Marshal Charles F. A. Portal therefore asked his Royal Navy colleague to provide another aircraft carrier to send 71 Spitfire fighters to Malta. In response to this need, Operations “Bellows” and “Baritone” were decided: it was planned that the Furious would first embark a first group of 39 Spitfires before leaving Great Britain and will be attached to convoy W.S.21S (i.e. that of “Pedestal”) to Algiers, where it would launch the Spitfires at 1 PM on August 11th (and this is “Bellows”). Then, it would return to Gibraltar, load another 32 Spitfires (sent from England on the steamship Empire Clive) and go out to sea again to launch them as well (Operation “Baritone”). The Spitfires would fly to Malta, where they would land at three different air bases. Eight destroyers based in Gibraltar, part of the reserve escort group, were made available to escort the Furious during her return voyage to Gibraltar: H.M.S. Keppel (Commander John Egerton Broome), H.M.S. Malcolm, H.M.S. Amazon, H.M.S. Venomous, H.M.S. Wolverine, H.M.S. Wrestler, H.M.S. Westcott, and H.M.S. Vidette. The latter, having set sail from Gibraltar, would join the H.M.S. Furious after escorting Force R to a predetermined point south of Mallorca, consisting of two tankers (Brown Ranger and Dingledale, which departed Gibraltar on August 9th) in charge of refueling the cruisers and destroyers escorting the convoy at sea.

H.M.S. Furious loaded the 39 Spitfires onto the Clyde, UK, from where she departed on August 4th along with the light cruiser H.M.S. Manchester and the destroyers H.M.S. Sardonyx (which left the group on the night of August 5th-6th) and Blyskawica (the latter Polish). On August 7th, H.M.S. Furious and H.M.S. Manchester joined convoy WS.21S, with which they crossed the Strait of Gibraltar on August 10th (H.M.S. Furious was to accompany the convoy only for the distance necessary to reach “flight” range from Malta). The following day, H.M.S. Furious, escorted by the destroyers H.M.S. Lookout and H.M.S. Lightning, separated from the main group and moved to a predetermined point south of the Balearic Islands, about 584 (or 550, or 635) miles west of Malta, where she launched her spitfires in the early afternoon of August 11th. It was precisely as the Furious was heading towards this point south of the Balearic Islands that it was spotted by Uarsciek.

Estimating the beta (which was 30°, portside, with alpha of 330°), Arezzo estimated the course of the British ship as 90°, opposite to that of Uarsciek, which was 270°. Considering the relative approach speed of 25-27 knots (the speed of Uarsciek was 9 knots, that of the aircraft carrier was estimated at 18), it made the decision to enter the launch circle with an attack course, remaining on the surface, to launch its torpedoes immediately.

In the meantime, other ships were sighted: a battleship, on alpha about 0° and beta 0°, and a smaller unit a little further to starboard. The sighting of the battleship allowed the crew to better appreciate the route of the enemy formation, which appeared to be sailing in the detection line. Deciding to attack the aircraft carrier, commander Arezzo della Targia had to find himself across the battleship. Preparing to attack, he ordered the helmsman to come 190°, and provided the launch chamber with torpedo angle data.

At 4:42 AM, in position 37°52′ N and 01°48′ E (approximately in the northwestern corner of the patrol sector south of Ibiza and Mallorca), from a distance of about 1,000 meters, Uarsciek launched two torpedoes at the Furious (another version mistakenly speaks of three torpedoes), from tubes 3 and 4, with alpha 5°, beta 80° to the left, 20° range to the left, angle of impact calculated as 105°, aiming angle of 25° and correction for parallax of 50 meters. There was a light east-southeast wind with force 2, the sea was calm (force 1-2), visibility poor.

The wake of the torpedoes was immediately very visible: from aboard Uarsciek a light signal was seen on the aircraft carrier, which it was believed to have sounded the alarm after having sighted the torpedoes. Another torpedo, 450 mm, was ready on board Uarsciek, but the commander decided to dive without launching it since the enemy battleship was at almost 800-900 meters away and considering it more important – as ordered by Supermarina – to launch the detection signal to allow the other submarines to attack. He orders the crash dive and as soon as he descended into the control room, he heard two muffled explosions, at very short intervals from each other, about 50 seconds after the launches.

At 4:47 AM the first discharge of depth charges was heard, extremely violent (probably a very large cluster). Uarsciek remained at a depth of 80 meters, following the action of the destroyers on the hydrophones. The bulk of the British line-up, meanwhile, appeared to have come to a standstill. At 4:55 AM, a second discharge of depth charges was heard, also extremely violent; two minutes later another one followed, very close, which causes some minor damage and causes Uarsciek to descend to a depth of 96 meters. At 5:04 AM, more violent explosions were heard; At 5:10 AM a new, violent discharge of depth charges, which, however, seems to be farther away than those that preceded it.

From the hydrophone measurements, the aircraft carrier seems to be stationary, while the destroyers feel moving. At 5:33 AM the aircraft carrier was heard starting again, and at 5:58 AM it was detected moving away for 53° (its bearing gradually widened, passing from 53° to 58°, 62°, 67°, 76° and 81°). At 6:56 AM, the hydrophones no longer perceived any sound of the aircraft carrier, which had now moved away, while the destroyers were clearly perceived from within hull. They continued to cross on the vertical of Uarsciek, passing over it, stopping and then starting again. But the launch of depth charges appeared to have stopped. During the whole hunt, the characteristic noises of the asdic was not heard.

Commander Arezzo got the impression that the research was being conducted with hydrophones. Finally, the destroyers also left and at 9:37 AM all sound sources were moving away in different directions, and at 9:39 AM Uarsciek was finally able to surface, about sixty miles south of Ibiza, and launch the discovery and torpedoing signal, communicating the composition, course and speed of the enemy formation.

At 10:55 AM, Admiral Syfret, on board the battleship H.M.S. Nelson, would be informed by the British intelligence service, via Malta, of the interception of an enemy detection signal relating to Force F (i.e. the set of naval forces at sea for “Pedestal”), sent a few hours earlier (6:20 AM according to a source, but the time zone is not very clear): it was the one sent by Uarsciek.

Uarsciek, the westernmost boat of the entire Italian-German submarine line-up, was the first Axis submarine to come into contact with British forces during the Battle of Mid-August. Its attack was unsuccessful, but its action was of great importance on a strategic level, because thanks to its signal of discovery, received by Rome at 10.25 AM, Supermarina had for the first time reliable information on the position and speed of the British naval forces after their entry into the Mediterranean, which had taken place almost twenty-four hours earlier.

On the Italian side, based on the explosions heard by Uarsciek after the launches, it would be mistakenly believed that the torpedoes launched by the submarine had hit H.M.S. Furious, damaging it and forcing it to return to Gibraltar. This claim was in fact announced in bulletin no. 806 of the Supreme Command, issued on August 12 (“In the western Mediterranean one of our submarines attacked, at dawn yesterday, a large warship of an unspecified type heavily escorted, hitting it with two torpedoes“) and then further clarified in bulletin no. 809 of 14 August (“The aircraft carrier ship hit on the 11th by the submarine Uarsciek and returned damaged to Gibraltar, it’s the Furious“).

According to British sources, Uarsciek attack was not noticed by British ships. The first submarine activity detected by them was noticed only at 8.15 AM that day, when the corvette H.M.S. Coltsfoot (Lieutenant K. W. Rous), part of the escort of Force R, sighted and reported two “dolphining” torpedoes, i.e. surfacing on the water, which passed quite far away, in position 37°56′ N and 01°40′ E. This is indeed rather strange, considering that Uarsciek report shows that the submarine was hunted with depth charges after the torpedoes were launched, which would assume that the enemy ships were at least aware of the attack. On the other hand, the essay “Operation Pedestal” by the historian Francesco Mattesini shows that at about five o’clock in the morning the British corvette H.M.S. Jonquil (Lieutenant Commander Robert Edward Heap Partington), also part of the escort of Force R but at that moment intent on maneuvering independently, heard the explosions of what were believed to be four depth charges.

However, the alarm was not raised. As for the sighting of two torpedoes by H.M.S. Coltsfoot, in a position very close to that of Uarsciek attack but four hours apart (at a place and time when there is no record of any attack by Italian or German submarines), the official history of the U.S.M.M. comments: “They could have been two of those launched by the submarine [Uarsciek] and that, due to the irregular operation of the self-sinking device, had remained afloat: this consideration is ours and can only have the value of a more or less reliable hypothesis”.

A little less than an hour after surfacing, Uarsciek sighted in position 38°01′ N and 01°38′ E an aircraft flying at medium altitude with a course of 45°, which led Uarsciek to return to the depths at 10.32 AM. Commander Arezzo believed that he has not been sighted, but in application of the circular A1/SRP of Maricosom (containing the general rules for submarines on war missions) he nevertheless decides to temporarily leave the area and go to Formentera, where he hoped to be able to intercept some returning enemy ships en route to Cape Palos.

At 12:18 PM, Uarsciek emerged and continued in the direction of Formentera, sailing on the surface, and at 2:05 PM sighted portside, in position 38°08′ N and 01°32′ E, a Fairey Swordfish biplane (in the report it is referred to as “a biplane of the Swordfish or Farei type for aircraft carriers“) approaching with an attack course. Although he did not consider him a very dangerous adversary, commander Arezzo della Targia decided to dive anyway because at 10.25 PM he received a signal of discovery relating to an aircraft carrier off the Balearic Islands. Immediately after diving, the crew of Uarsciek heard the explosion of two small-caliber bombs. Submerged navigation continued until 8.59 PM, when the submarine resurfaced and began to cross off the coast of Formentera.

August 12th, 1942

At 1.50 AM Uarsciek dove briefly to perform hydrophonic listening. The hydrophones detected a rather uncertain source for 312°, and considering the direction of the sound, Commander Arezzo deduces that they must be neutral merchant ships. Back on the surface, the submarine dove again at 6:05 AM to begin approaching the assigned area. Depth charges and explosions of aircraft bombs were heard several times, at varying distances; on board they were interpreted as a sign of the attacks in progress against the British convoy by Italian-German submarines and aircraft.

At 1:32 PM, Uarsciek’s hydrophones detected a turbine noise of 188°. The bearing then changes to 198°, 218° and 240°, after which it gradually decreases, while the intensity (1-2) remains constant. The submarine followed the source of this noise for a long time, at the same time exploring the horizon with its periscope. Then, at 3:20 PM, it emerged approaching the noise on the surface. Twenty minutes later a column of water four- or five-meters high was sighted, approximately two-quarters aft of the starboard beam, but no sound of an explosion was heard. Commander Arezzo also got the impression that it was a bomb dropped from a plane very high on the horizon, or the explosion of an electric torpedo, so he decides to dive to continue the hunt underwater. The hydrophones continued to signal a source with constant force (2-3) and variable direction between 180° and 240°. Believing that it was a destroyer or a submarine destroyer that sweeping on patrol ahead of some larger ship, Arezzo ordered to assume a course of 210°, equal to the average bearing. Uarsciek continued on this course throughout the afternoon, continuing to hear the source on the hydrophones, but without being able to spot anything.

At 8.13 Pm the boat was ordered by Maricosom to move to a new sector, so Arezzo decided to interrupt once and for all the fruitless chase of the ship that was producing the noise. At 7 PM, in fact, the Command of the Submarine Squadron issued orders for Uarsciek, Dagabur, Brin and Volframio to move westwards, at the same time informing them that a part of the British ships (the heavy support force, which was to accompany the convoy only to the entrance of the Strait of Sicily, and then return to Gibraltar) had reversed course.

At 10:00 PM Uarsciek emerged, and the crew noticed a strong smell of naphtha, which was attributed by the captain to some significant loss of fuel, but in the darkness, nothing can be seen. The submarine therefore continues to sail on the surface towards the newly assigned sector.

August 13th, 1942

At 2:50 AM, a new order arrived, moving the area assigned to Uarsciek even further west. At four o’clock in the morning, the odor of naphtha was again smelled, but the leak could not be detected. Commander Arezzo summons Chief Engineer Cristini and questions him about it, but after an inspection he claimed to rule out any leaks.

At 6.05 AM, Uarsciek dove and began occult navigation. Throughout the rest of the day, and especially around the hours of listening to the SITI (TN messages from base), very frequent discharges of aircraft bombs were heard, sometimes very close, and planes passing near the boat were heard continuously, sometimes clearly perceptible through the hull. At 5:19 PM a telegram was received from Maricosom reporting the presence of a battleship and three destroyers, with a course of 270° and a speed of 24 knots, sighted at 1:30 PM in square 0462. Commander Arezzo, having made some calculations, judges that if the reported formation, once it reaches the south of Formentera, would movein the direction of Alboran (as he considers probable), Uarsciek could succeed in intercepting it at the northern end of the new area assigned to it, around midnight. The submarine then continued to cruise towards the assigned area.

At 9:25 PM, Uarsciek emerged, and this time the loss of naphtha was unmistakable and abundant: it was a damaged naphtha tank. On the water there are very visible patches of oil, and it became evident that the insistent hunting by the planes suffered during the day was caused precisely by this tangible, conspicuous sign of the presence of the submerged submarine. Captain Arezzo listened to the opinions offered by Chief Engineer Cristini, who stated that he considered it impossible to eliminate the leak with the means available on board> Therefore the captain decided to abandon the ambush, informing Maricosom of it by radio – as provided for by circular A1/SRP – even though he believes that by doing so (breaking the radio silence) Uarsciek was exposing itself to the risk of being radio localized.

At 11.45 PM, in position 37°02′ N and 00°09′ W, a white light was sighted for 350° over the water; Uarsciek immediately heads towards it, but after a few minutes the light begins to expire rapidly at the stern, until it went out. Commander Arezzo, believing that it was a Short Sunderland anti-submarine seaplane that has landed on the surface of the sea to listen, orders a crash dive. Once submerged, the submarine detects aircraft noise on the hydrophones that covers the entire area, and which was indeed clearly perceptible through the hull. At midnight the hunt began with frequent discharges of bombs presumably from several planes (given the number of bombs dropped) whose noise could be heard in the hull. Some of the discharges explode quite close. The systematic nature of the hunt leads Arezzo della Targia to believe that Uarsciek must certainly have been sighted and he speculates that the Sunderland located him by direction finding – as he feared – and that they had been lurking for some time, waiting for his arrival.

August 14th, 1942

At 1:37 AM, the hydrophones detected noises of approaching force 2 turbines, on 80° detection. Commander Arezzo believes that this was the formation reported by Maricosom a few hours earlier, which arrived on the scene at the time estimated by the calculations previously made. However, the approach of the noise of the turbines was accompanied by an intensification in the dropping of bombs by the planes. Evidently, they were trying to preclude Uarsciek from any attempt of attacking the approaching ships. At 2.50 AM the sound source detected by the hydrophones reached maximum intensity, on detection bearing 183°. The turbines could be felt through the hull of the boat. Uarsciek seemed to be clearly tending to steer to starboard against the will of the captain, who had to order a strong rudder angle to bring it back on course. At first Arezzo thought that the rudder indicator may be out of calibration, but then it turned out to be perfectly working, which lead the commander to believe that Uarsciek was in a vortex of current, perhaps generated by the explosions of the bombs.

Uarsciek crew members pose for a photo after the Battle of Mid-August, August 14, 1942.

Bottom right, Commander Arezzo della Targia; clinging to the pole waving the “Jolly Roger”, sailor helmsman Franco Calia

(Coll. Davide Calia)

On the other hand, he believed it is unlikely that the magnetic compass could have gone out of order by the presence of the magnetic masses of British ships, since the hydrophone bearing widens very regularly. At 3:04 AM, the sound source reached its maximum intensity, then began to move away. At 4:14 AM it was detected with force 1 for bearing 249°. At 4.30 AM Uarsciek emerged in position 37°08′ N and 00°15′ W, but spotted seaplanes resting on the sea again, and thus it dove again. As soon as they spotted the submarine emerging, the planes took off. Their noise was heard again both on the hydrophones and through the hull, and again the bomb drops began, several times, with some explosions quite violent and close, but not enough to cause damage.

At 6.10 AM the crew heard a sound on the hydrophones again for bearing 120°, intensity 1; very far away, since the hydrophones picked it up at a minimum. At 6.30 AM the source was intensity 2 on bearing 110°-120°; Half an hour later, another turbine was detected for bearing 98°, force 1, but this ship also passed a great distance. The maximum intensity was 2. At 7:50 AM, nothing could be heard. For the rest of the day, the explosions continued, becoming more and more sporadic.

At 6.40 PM, after a tour of exploration at the periscope to be sure of being under the Spanish coast, Uarsciek emerged and began the return navigation.

August 15th, 1942

At 6.30 AM, Uarsciek, having reached the traverse of Cape de la Nao, in an area of hidden navigation, dove. It resurfaced at 2 PM and continued on the surface, passing during the day outside the Balearic occult navigation zone.

August 17th, 1942

At 2.40 AM, Uarsciek landed on the conventional point “B” of Asinara, and at 8.20 AM it moored at La Maddalena.

For the action of Mid-August, which on the Italian side mistakenly believed to have led to the torpedoing of enemy ships, commander Arezzo della Targia was decorated with the Silver Medal for Military Valor, with the motivation “Commander of a submarine of high professional ability, he participated with serene courage and indomitable aggressive spirit in the Mediterranean battle of mid-August, decisively attacking a large enemy convoy powerfully escorted by naval forces and Aerial. With the timely and effective launch of torpedoes, it inflicted certain losses on the enemy formation, causing the sinking and torpedoing of warships and merchant vessels. He demonstrated in his arduous brilliant action chosen military virtues and a tenacious will to victory.”

Also decorated with the Bronze Medal for Military Valor will be the commander in second lieutenant Remigio Dapiran, who was injured during the depth charges bombardment (motivation: “Officer in 2nd submarine, he participated in the Mediterranean battle of mid-August against a large enemy convoy strongly escorted by naval and air forces, assisting the commander with boldness and skill in the daring actions against the adversary. Although wounded during the hunting action, to which the unit was subjected, he continued to bravely hold his combat post, demonstrating high military qualities”).

The chief engineer, Lieutenant of the Naval Engineers Armano Cristini, the aspiring midshipman Francesco Florio, the chief electrician third class Ilario Mazzotti, and the second chief engine engineer Pietro Battilana were also decorated. For Arezzo della Targia, Dapiran, Mazzotti and Battilana, however, the decoration came posthumously: the royal decree sanctioning the awarding of their medals, in fact, was dated December 18th, 1942, three days after the sinking of Uarsciek and their death.

September-December 1942

Uarsciek makes several training runs.

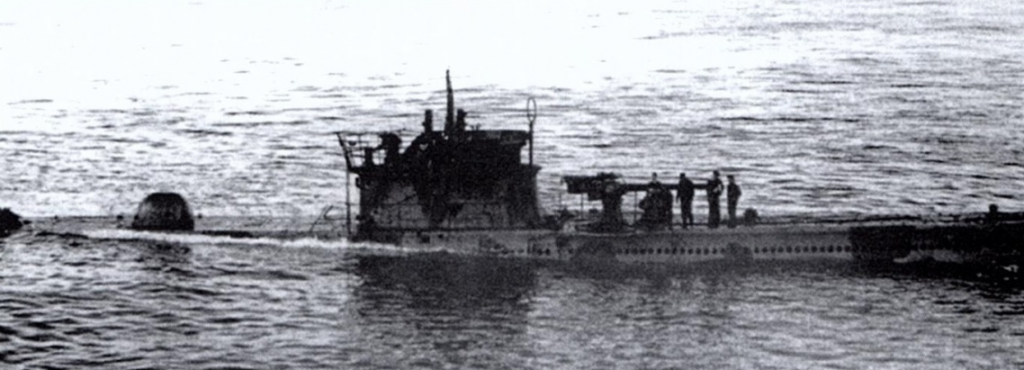

Uarsciek navigating toward La Maddalena

(From the magazine “Storia Militare”)

October 31st, 1942

In the middle of the battle of El Alamein, Uarsciek sailed from Messina to Tobruk at 6.45 PM, on a transport mission: it had 19-20 tons of ammunition on board.

November 4th, 1942

The boat arrived in Tobruk at 1:15 PM, disembarked the ammunition and left again at 6:15 PM, with orders to carry out a patrol off the Egyptian coast. On the same day, the British attacks on El Alamein succeeded, and the long retreat of the Axis troops began.

November 7th, 1942

In the morning, Maricosom, in anticipation of the possible passage of an enemy convoy in the Strait of Sicily, orders Uarsciek and other submarines (Ascianghi, Granito and Dessiè) to reach patrol areas in the Strait of Sicily.

The convoy sighted is part of the Anglo-American invasion fleet at sea for the operation “Torch”. The ships that were part of it did not cross the Strait of Sicily, but instead participate in the landing on the coasts of Morocco and Algeria, which was considered a more likely target even by Supermarina which in fact had deployed twenty-one submarines in the western Mediterranean: the dispatch of Uarsciek, Ascianghi, Granito and Dessiè to the Strait of Sicily was merely a precautionary measure for the hypothesis, which cannot be excluded a priori although considered unlikely, of sending a convoy heading east.

November 9th, 1942

Due to damage suffered during the patrol, Uarsciek had to set course for Tripoli, where it arrived at 1.30 AM, stopping there for five days to receive some temporary repairs.

November 14th, 1942

The boat left Tripoli at 1:00 PM to return to Italy.

November 16th, 1942

Uarsciek arrived in Messina at 2.25 PM and underwent other work to get it back into working order.

Another picture of the ’Uarsciek

(ANMI Montebelluna)

The Sinking

At 5:25 PM on December 11th, 1942, Uarsciek, under the command of Lieutenant Gaetano Arezzo della Targia, sailed south of Augusta for a patrol south of Malta.

This was to be one of her last missions before a period of major maintenance work scheduled for February 1943, although the Special Commission of Inquiry set up in early 1947 to review her sinking described the vessel as “in good working order” at the time of the loss. Not long before, Uarsciek had already undergone work to solve problems with the diesel engines, which had come to light during the Battle of Mid-August. Work had also been carried out to resize the conning tower to reduce diving times, as well as work on the machinery to make it quieter.

Sailor Domenico Di Serio, embarked on Uarsciek in Naples, met on board an old acquaintance of his, the chief electrician Ilario Mazzotti (in the past embarked with him on another submarine, the Malachite), who had announced that the submarine would soon have to go to Pula for a period of major works. Leaving Naples, in fact, Uarsciek had moved to Messina, where the crew had waited for the order to continue to Pula, instead, it was time to reach Augusta, and then to put to sea for a mission off Malta.

Of the 47 crewmen on board that outing, only 30 % had already served on Uarsciek in previous missions; 15 % were conscripts on their first embarkation, 55 % submariners had transferred to Uarsciek from other vessels. Commander Arezzo della Targia was feverish, in poor health. Chief engineer, Lieutenant of the Naval Engineers Lorenzo Coniglione, embarked a couple of months earlier, had previously been disembarked from Uarsciek due to a serious nervous breakdown.

On the other hand, the sub-chief electrician Brunetto Montagnani, who had already “played” death for before (TN was reported as a casualty), had arrived just before this mission. Assigned to the crew of the submarine Medusa, he was at home on leave when it was sunk with the death of 58 of the 60 men on board, in January 1942. After the loss of the Medusa he was transferred to Uarsciek, where he had the surprise of meeting as commander lieutenant Arezzo della Targia, who was embarked on the Medusa (he had been one of the only two survivors): “At embarkation time, when he reads Montagnani, he looks up and recognizes me. He greets me joyfully, happy to be together again after the tragic events.” However, Montagnani had been ordered to transfer to Taormina for a period of “oxygenation”, which the submariners had to undergo after accumulating a certain number of hours underwater. Montagnani remained on the ground while Uarsciek left for its last mission. He would escape by chance on a third occasion, remaining on land – because he had not been warned, returning from a leave – while the steamer that was taking his unit to Corsica was sunk.

The orders received by commander Arezzo from the X Grupsom of Augusta indicated that Uarsciek, along with the submarine Topazio, would reach a patrol sector south of Malta to operate with total offensive-exploratory tasks, and to provide for indirect protection of the motor ship Foscolo, navigating from Naples to Tripoli, which had left on December 12th with a load of fuel and ammunition. Uarsciek and Topazio were to position themselves in sectors close to each other, about fifty miles south of Malta, and prevent attacks by enemy ships, and especially by Force K, which was expected to exit to attack the convoy. Force K would have fallen into the ambush set by the two submarines.

The situation in North Africa looked dark: a month earlier the Italian-German forces had suffered the decisive defeat at El Alamein, and on the same days in which Uarsciek mission took place they were fighting at El Agheila, on the western edge of Cyrenaica, to try to stop or at least slow down the British advance. Casualties on the route to Libya had soared in the face of intensified Allied air and naval warfare.

Foscolo’s voyage would also end at the bottom of the sea, on December 13th, off Cape Lilybaeum. Uarsciek would follow her two days later. (According to an article by Aldo De Florio in the February 2014 issue of UNUCI magazine, indeed, Uarsciek was supposed to meet with the Foscolo in the south-east of Sicily, after the crossing of the Strait of Messina by the motor ship; the meeting, however, could not take place due to a variation of the order of operations following which the Foscolo changed its course, coasting along western Sicily and being sunk by torpedo bombers. Uarsciek ran into enemy destroyers while waiting in vain for the Foscolo). Within a month and a half, all of Libya would be lost.

Uarsciek reached the sector assigned for the ambush at five o’clock in the morning of December 13th, 1942, Sunday. For nearly 24 hours nothing happened, then, in the early hours of December 14th, two light units were sighted at a great distance, too far away to attempt an attack (they were perhaps part of a formation – estimated to be composed of three cruisers and two destroyers – already sighted and attacked, a few hours earlier, by the Topazio, which at 1.40 AM had launched three torpedoes without success).

Uarsciek continued its patrol. The sub-chief torpedoman Michele Caggiano, from Taranto, would later recount that on the evening of December 14th, around ten o’clock, commander Arezzo della Targia had called him to the bridge, since he was the food delivery person, to have a pizza prepared for midnight for the whole crew, to celebrate Saint Lucia, patron saint of his Syracuse, whose celebration occurred that day.

Even the Istrian sailor Domenico Di Serio, a veteran submariner but on his first patrol on Uarsciek (he had disembarked from the Malachite the previous December 5th, in Naples, and had immediately received orders to pass on Uarsciek, which had immediately left for Messina), later recalled the special lunch for the whole crew organized in honor of Santa Lucia, to whom the commander was particularly devoted: “We had a wonderful two hours. Then we were ordered: the party is over, everyone back at their post.”

Nothing else happened until about 3:00 AM on December 15th, when Uarsciek, while on the surface, sighted at close range, about 45-50 miles south/southeast of Malta, a group of units that were identified as a cruiser and three destroyers. There were only two destroyers, the British H.M.S. Petard (Lieutenant Commander Mark Thornton) and the Greek Vasilissa Olga (Lieutenant Commander Georgios Blessas), sailing from Benghazi – from where they had departed on December 14th for Malta.

According to the narration of the torpedoman Michele Caggiano, it was the stern lookout, just as they were preparing for the changing of the guard, that sighted at a short distance a ship that seemed to be following the submarine emitting three green light signals, evidently signals of recognition. Domenico Di Serio was in the control room at the time. When the dismounting lookouts came down from the bridge for the changing of the guard, Di Serio asked one of them what the weather was like, and he replied: “It’s cold, it’s foggy and you can’t see it an inch from your nose”. Before the lookout had even finished speaking, the alarm was sounded. From the conning tower they were asked for the signs of recognition, which Di Serio himself prepared daily with lamps of various colors. Uarshiek broadcast the prescribed signals but received no response.

When it became clear that the ship sighted was an enemy ship, heading towards Malta, and finding Uarsciek in a favorable position for an attack, commander Arezzo della Targia immediately ordered two torpedoes to be launched against the enemy ships from the stern tubes (tubes 5 and 6), after which he ordered a crash dive to disengage, assuming a course of exit. As the submarine descended into the depths, two loud explosions were heard on board, which led the crew to mistakenly believe that they had hit one of the enemy ships. No explosions of depth charges were heard (but since the torpedoes had not hit, it is possible that the two loud explosions heard on board were depth charged), while the sound of the sonar of the enemy ships intent on the search could be heard through the hull.

According to the British version, Uarsciek was surprised on the surface at 3.05 AM (Italian time; 4.05 AM according to the time followed by the British units) on December 15th, in position 35°08′ N and 14°28′ E (or 35°08′ N and 14°22′ E), by the H.M.S. Petard’s lookouts, who sighted it on portside forward, in conditions of calm sea. At first, British lookouts thought it was a surface ship. When they realized that it was instead a submarine that had surfaced, Commander Thornton initially believed that it could be the British submarine H.M.S. Umbra (other sources mistakenly speak of the H.M.S. Ultimatum, but the latter was at that time under construction in the United Kingdom), returning to Malta after a mission in the Gulf of Hammamet. H.M.S. Petard then made the reconnaissance signal, and it was at that point that the Italian submarine dove and launched its torpedoes. Considering the two versions, the sighting was probably reciprocal and simultaneously.

H.M.S. Petard alerted Vasilissa Olga with two loud siren whistles and avoided the torpedoes – spotted despite the darkness thanks to their phosphorescent wakes – with the maneuver, veering in their direction and passing between their wakes (Greek sources claim that the two torpedoes would have passed forward of the Vasilissa Olga, at a short distance), after which both exploded. At 3:10 AM, they unleashed a heavy hunt with depth charges. H.M.S. Petard, which had almost immediately obtained ASDIC contact, made a first attack at that time with the launch of a single depth charge and ordered the Vasilissa Olga to circle around that position, describing circles with a width of two miles. At a certain point, Uarsciek came to the surface unexpectedly, and then immediately returned to the depths, and the Petard attacked it with ten depth charges, and then ordered the Vasilissa Olga to attack in turn. The Greek destroyer launched six depth charges, set to explode at a depth between 45 and 90 meters; this third and final attack caused serious damage to the essential equipment of Uarsciek, especially in the aft compartment, to the point of forcing it to maneuver the boat for a rapid surfacing about 180 meters from H.M.S. Petard.

On the Italian side (both according to the official version and according to the memory of the survivor Michele Caggiano) it appeared that, during the rapid dive maneuver following the launch of the torpedoes, the submarine sank excessively, falling rapidly to a depth of 160 meters (twice the test depth) heavily down by the bow. This problem, due to the failure to empty the rapid tank, made the commander give air to the double bottoms, to stop the dangerous descent and climb back to a more adequate depth. This maneuver, however, had an excessive result. Perhaps because too much air had entered the double tanks, Uarsciek climbed too quickly and ended up surfacing involuntarily with the entire conning tower, making it easier for destroyers to spot it. Immediately afterwards, the submarine returned to the depths, this time with a control maneuver, but by now the enemy ships knew where it was and immediately subjected it to heavy bombardment with depth charges, seriously damaging it and forcing it to surface once and for all.

Domenico Di Serio later recalled that Uarsciek, once it had descended to a depth of 80 meters, had remained motionless trying not to make noise, but in vain: it had been located and hit by the explosion of a cluster of depth charges – eight, according to his memory – which turned off the lights and even detached the paint from the bulkheads of the submarine, causing the fragments to fall on the floor “like a snowfall”.

Maneuvering with a single engine, Uarsciek descended again – to 100 meters, according to Di Serio – again trying to minimize the noise, but shortly afterwards four more depth charges exploded very close together, all around the hull. Uarsciek skidded under the violence of the detonations, the light went out again, many lamps broke, water began to seep into the bilges from the propeller shaft cases. Lighting was restored, but this time the damage was very serious; Commander Arezzo della Targia gathered all the officers in the control room, and Chief Engineer Coniglione explained that the hull was badly damaged, there were dangerous waterways: “Commander, we can remain in these conditions only for a short time. Either we emerge, or it’s the end for everyone, because the water keeps coming in and weighs down the boat even more.” Arezzo remained thoughtful for some time, then called all the personnel to the control room and announced his decision: “Let’s face the enemy.” His intention was to try to escape to the surface using the diesel engines, but it was a hopeless attempt. The personnel assigned to the weapons took their places in the conning tower, then the order was given to emerge.

Sub-chief Michele Caggiano would later recall that when they emerged, Commander Arezzo gave the order to arm the cannon to face the enemy units in a fight on the surface: “Let’s take them out like this!“, he urged his men. Caggiano himself, being part of the armament of the cannon, reached the hatch of the forward hatch, which it was his task to open; Grabbing the hatch handwheel to release it, he realized with some astonishment that it appeared to open much more easily than usual, without requiring much effort. This was due to the pressure inside the submarine, which had increased a lot during the bombardment: to the point of making the hatch open abruptly and Caggiano himself being thrown out; he landed on the left side of the deck, between the hatch and the conning tower, with his feet in the air. The deck was still half-submerged, and Caggiano realized that he was falling towards the stern. With his left hand he grabbed a cockerel from the lid of the left ready-use stowage, thus avoiding being dragged into the sea. Before the main deck had even fully surfaced, a beam of light from four o’clock lit up the conning tower in full, immediately followed by a storm of machine-gun fire, tracers that left behind green light trails.

Domenico Di Serio, staying below deck, could hear the bursts of machine-gun fire hitting the hull of the Uarsciek. The machine guns were outside their quarters, one pointed towards the sky and the other towards the enemy, but they could not be reached, like the cannon: anyone who tried to approach was immediately hit. Shrapnel even fell into the control room. Commander Arezzo, on the bridge, gave the order for everyone to go on deck.

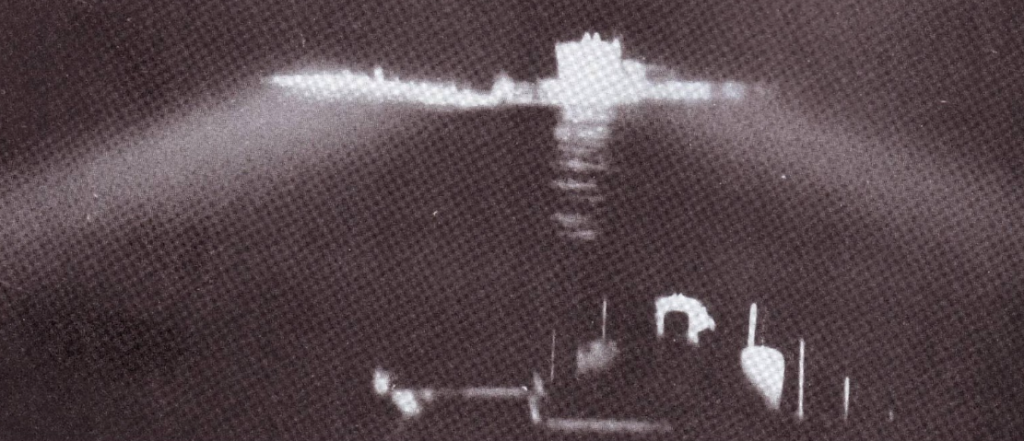

Uarsciek illuminated by the floodlights of H.M.S. Petard and Vasilissa Olga

(“Ultra versus U-Boats” by Roy Convers Nesbit)

Commander Thorton of H.M.S. Petard had previously missed an opportunity to capture an enemy submarine (the German U 559, sunk on the previous October 30th: surfaced after being seriously damaged by depth charges, and immediately abandoned by the crew, the U-boat had been boarded by a squad of H.M.S. Petard who had seized ciphers that later proved to be fundamental for the decryption of the “Enigma code“, but the submarine had sunk shortly afterwards taking with it a British officer and a sailor trapped on board), and he was determined, this time, to capture his opponent intact, to take possession of the ciphers and secret documents on board.

As soon as the Italian boat emerged, therefore, he had it illuminated with searchlights – according to a source, the Vasilissa Olga also pointed its searchlights at Uarsciek – and ordered the servants of all his 20 and 40 mm machine guns to open fire on it, with the intention of preventing any attempt at reaction or self-sinking by the Italians, without causing too much damage to the submarine (historian and submariner Clay Blair writes that the British Admiralty’s policy was to force the crews of submarines to stay below deck with machine gun fire to prevent them from attempting to scuttle, and that Thornton complied with these provisions).

The firing of the 20 mm Oerlikon machine guns and the deadly 40 mm quad “pom-poms” had a devastating effect on the crew of Uarsciek, mowing down almost everyone who tried to climb the deck or conning tower. Twice the gunners of H.M.S. Petard, deeming it excessive to continue strafing, stopped firing, and twice Thornton ordered them to open fire again; according to the book “The Enigma Code” by Hugh Sebag-Montefiore, H.M.S. Petard’s commander himself personally took up a machine gun and opened fire on the men visible on the bridge of Uarsciek. The circumstances and nature of this last action remain rather controversial: while some British sources justify it as a normal act of war aimed at crushing any attempt at reaction or self-sinking by the Italian crew (“the submarine, badly damaged, showed no sign of being abandoned by the crew and, as was logical, H.M.S. Petard continued to fire, not to kill the shipwrecked, but to kill the shipwrecked, but to force them to hasten the abandonment of their ship“), other authors believe that Thornton committed a grave excess, killing men who were attempting to surrender.

Thornton’s orders to his gunners, repeated twice, to reopen fire should also be placed in this perspective: the latter would have hesitated to carry it out because, unlike their commander, they believed that the survivors were now surrendering and that it was not necessary to kill them. The opinion that Thornton’s behavior would have represented an “excess” seems to be shared by several members of the crew of H.M.S. Petard, starting with the ship’s doctor William Prendergast and the radio operator Reg Crang, as well as by various survivors of Uarsciek.

On the other hand, another sailor of the H.M.S. Petard, Trevor Tipping, appears to be of a different opinion. In an interview given after the war, he stated instead that he considered the fire action of H.M.S. Petard completely justified, given that the men who came out on deck on Uarsciek were running towards the gun: “The question was, either us or them. Better them than us.” Answering a specific question, Tipping also added that Prendergast had been impressed by what he had seen because he was a doctor who had recently joined the Navy, and that “A doctor’s opinion of war is different from that of a combatant“. According to Tipping, the rest of the crew had not been particularly impressed by the carnage, it had been a legitimate act of defense on the part of H.M.S. Petard and in any case those sailors were now accustomed to similar scenes (although Tipping himself mentioned in the interview that “some people” did not “like” the order to fire on the men running on the deck of the submarine, but that Commander Thornton had said they were trying to arm the gun, so “it’s either us or them.“)