Gondar was a coastal submarine of the Adwa-class (698 tons displacement on the surface and 866 tons submerged). During World War II, the boat completed a total of 4 patrols, covering 3,440 miles on the surface and 534 submerged for a total of 33 days spent at sea.

Brief and partial chronology

January 15th, 1937

Setting up in the Odero Terni Orlando del Muggiano shipyards.

October 3rd, 1937

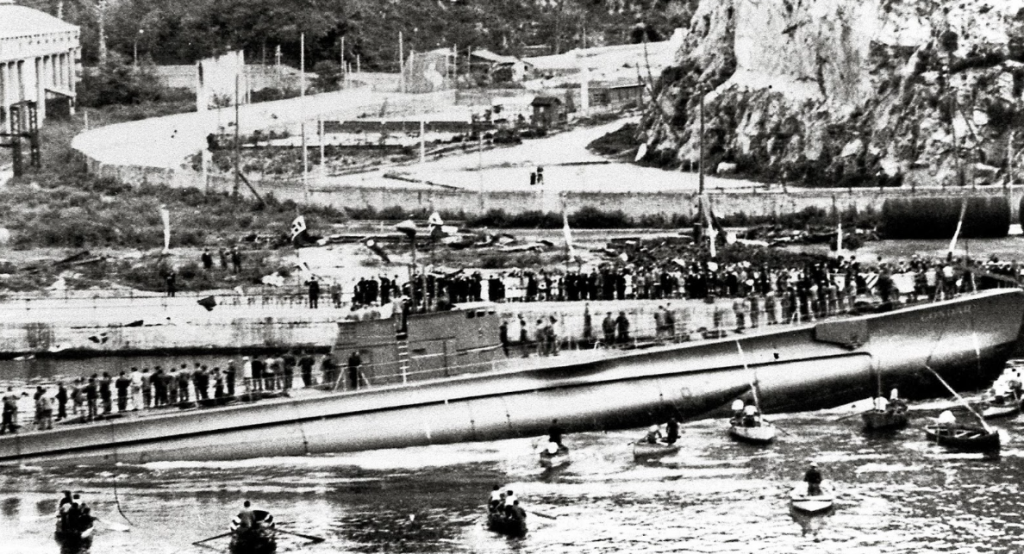

Launch in the Odero Terni Orlando del Muggiano shipyards.

The launch of the Gondar in Muggiano, La Spezia

February 28th, 1938

Entry into service.

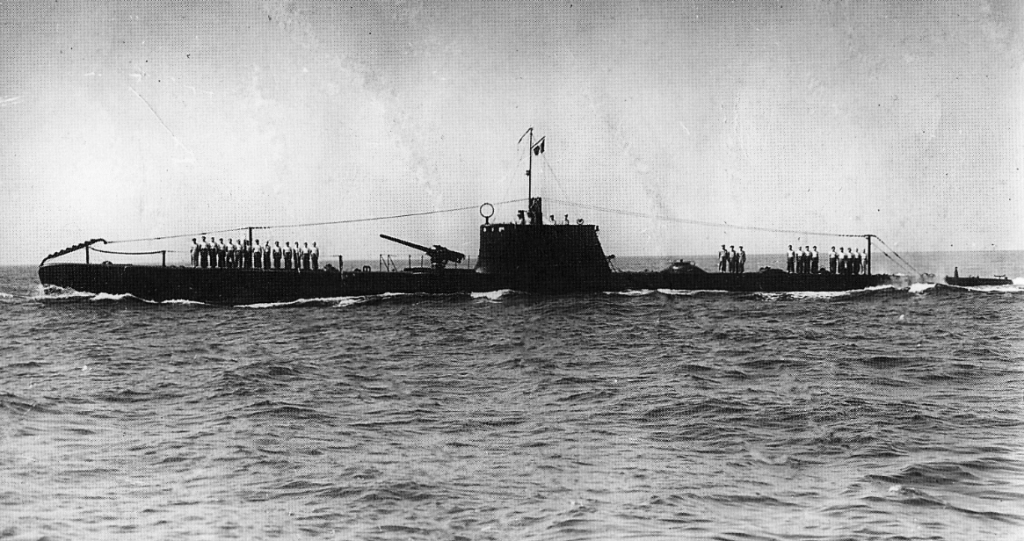

The Gondar near La Spezia in 1938

June 10th, 1940

On the date of Italy’s entry into the World War II, Gondar was part of the XV Submarine Squadron (based in La Spezia, under the command of the I Grupsom), which it formed together with the twin boats Neghelli, Ascianghi and Scirè. Gondar was immediately sent into on patrol west of the Gulf of Genoa, off the French Riviera.

June 14th, 1940

Gondar was unsuccessfully attacked by a Vought SB2U Vindicator dive bomber (V-156) of the AB3 squadron of the French naval aviation, operating in support of the French naval squadron (cruisers Foch, Algerie, Dupleix and Colbert and eleven destroyers) which was carrying out a bombardment of Genoa and Savona. On the same day, the submarine returned to base without encountering any enemy ships.

The submarine Gondar at sea

June 18th, 1940

The boat set off for the second war patrol (TN under the command of Lieutenant Piero Riccomini).

June 25th, 1940

The boat returned to base.

August 5th, 1940

Gondar was sent on patrol east of Gibraltar, along with the submarines Ascianghi and Marcello.

August 16th, 1940

Gondar returned to base.

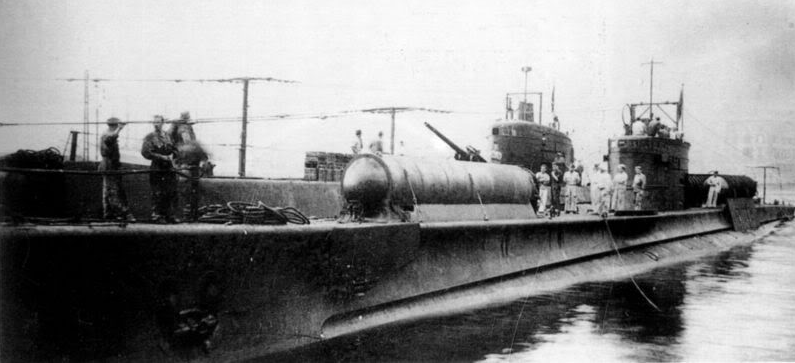

The Gondar in La Spezia being fitted with the SLC carriers

Slow-moving Torpedoes

When Italy entered the World War II, on 10 June 1940, the I Flotilla MAS, the special unit of the Regia Marina in charge of preparing and carrying out raids with insidious means against enemy ports (only on March 15th, 1941, this unit would take the name of X Flotilla MAS, with which it would become famous), was far from being ready for action. Formed just over a year earlier, on April 23rd, 1939, the Flotilla was still in the training phase, as well as short of resources.

At the end of July 1940, Admiral Raffaele De Courten, superintendent of assault craft at Supermarina, verbally invited the commander of the I Flotilla MAS, frigate captain Mario Giorgini, to prepare an attack on Alexandria – the Royal Navy’s main base in the Mediterranean – with the use of Slow Running Torpedoes (SLC), better known as “pigs”.

This first mission, called “G.A. 1”, ended in tragedy before it even began: the submarine in charge of taking the SLCs to Alexandria, Iride, was in fact sighted by British air reconnaissance and sunk by torpedo bombers in the Gulf of Bomba, in Cyrenaica, together with the support ship Monte Gargano.

This was on August 22nd, 1940, but at the same time two other submarines were already undergoing the modification works necessary to transform them into carriers for slow-moving torpedoes, they were Gondar and the twin boat Scirè

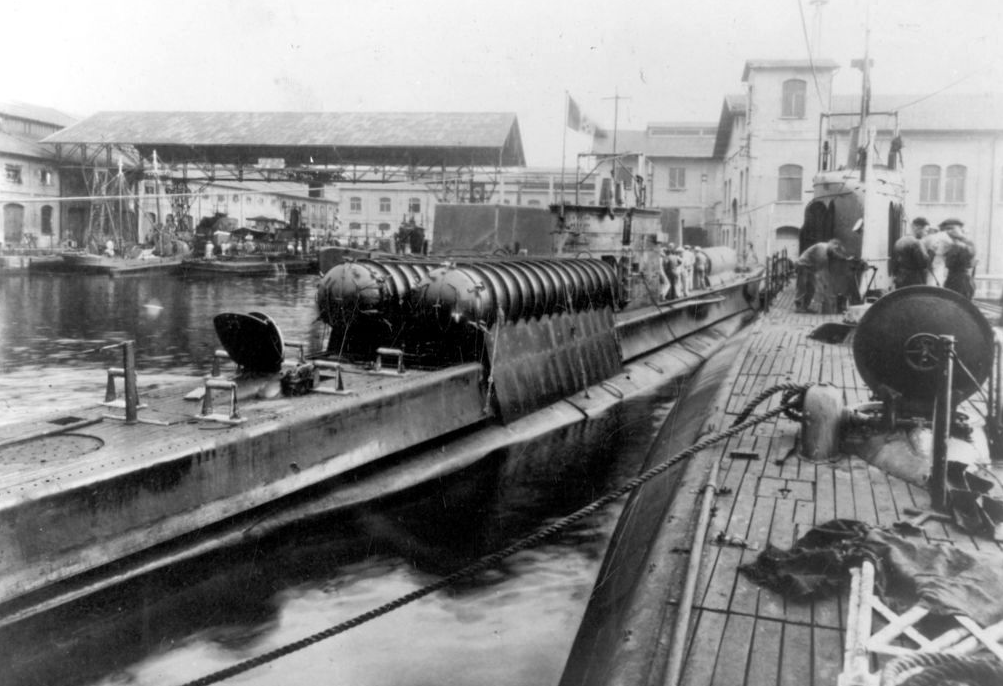

Gondar with the SLC carriers fitted docked next to the Argo

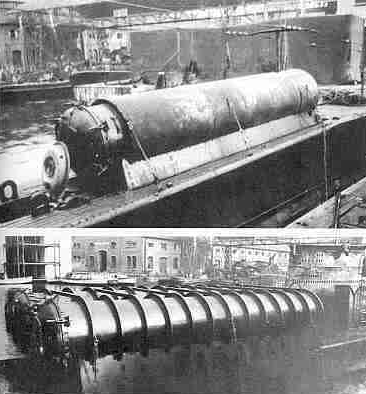

While the system for the transport and release of the SLCs adopted on the Iride was very rudimentary (the assault craft were simply placed and harnessed on two pairs of saddles on the deck of the submarine), Gondar and Scirè (in August-September 1940) underwent more specific adaptation works. Both submarines were equipped with watertight container cylinders, positioned on deck, in which to place the SLCs (the Gondar, on which work began at the end of August 1940, was the first submarine of the Regia Marina to be equipped with such cylinders).

This device, designed by the Odero Terni Orlando shipyard in La Spezia, made it possible, among other things, to dive and activate the SLCs up to a depth of 90 meters, against the maximum of only 30 meters allowed by the method used on the Iride. In addition, the support of any other unit was not necessary, and it was possible to transport the SLCs from the start, eliminating the intermediate stopovers that had been fatal to the Iris.

There were three cylinders, one located forward of the conning tower and the other two (side by side) aft of the same. Each of them weighed 2.8 tons and could withstand, as mentioned, a pressure equal to that of 90 meters deep, i.e. the maximum test depth of the Adwa-class submarines. The cylinders were connected to the submarine (by means of a system of valves and pipes that could be operated from inside the submarine) to be flooded (each cylinder could hold 21.75 tons of water) and drained, as well as for the ventilation necessary for the SLC batteries (there were also electrical systems to keep the latter charged). Each cylinder was closed by a hemispherical watertight hatch, with side opening. The forward cylinder of Gondar had no reinforcing rings, the only difference compared to those of the submarine Scirè. On the other hand, to lighten the overall weight, the 100/47 mm deck gun, its ammunition, two torpedoes and other weights deemed superfluous were eliminated.

Top, the forward container without the reinforcing rings. Below the aft contains

There were two possible methods for the release of SLCs. One was for the submarine to surface (with only the top of the conning tower above the surface), stationary, and for the SLC operators to exit from inside the unit through the upper hatch, walk along the deck to the cylinders, which in the meantime was flooded, open the hatches, extract the SLCs, close the hatches and set the SLCs in motion, heading towards the target.

In the second case, however, the submarine had to lie on the seabed at a depth of a dozen meters; the raiders, equipped with breathing apparatus, would escape from the floodable escape compartment, opened the cylinder doors (meanwhile flooded), extracted the SLCs and headed towards their targets.

Already a few days after the sinking of the Iride, the Chief of Staff of the Regia Marina, Admiral Domenico Cavagnari, sent a new mission order to Commander Giorgini. This time the I Flotilla MAS was to conduct an almost simultaneous attack against both Alexandria (headquarters of the Mediterranean Fleet) and Gibraltar (headquarters of Force H), again using SLCs.

Gondar and Scirè, on which the work of adapting to SLC carriers (carried out in the shipyard of La Spezia) was being completed, were therefore immediately chosen for this mission: Gondar was to attack Alexandria, Scirè Gibraltar.

Lieutenant Francesco Brunetti, former commander – and shipwrecked – of the lost Iride in the ill-fated operation “G.A. 1” was appointed to command the Gondar (TN replacing Lieutenant Piero Riccomini). He had asked to be able to complete the mission begun with the Iride, to avenge his men who perished in the sinking. They wanted to avenge the defeat and the deaths in the Gulf of Bomba. Hitting Alexandria would now become a matter of principle for the 1st Flotilla MAS, but it would be more than a year before the enterprise would be crowned with success.

On September 19th, 1940, Supermarina sent Commander Giorgini order number 4973, which sanctioned the start of Operation “G.A. 2” against Alexandria in Egypt. The raid was scheduled to take place on the night of September 28th-29th (to take advantage of the moon at the last quarter), or, in case of delays (due to interference by British ships or aircraft, or due to slow navigation), the following night. The release of the SLCs was to be accomplished in half an hour.

S.L.C.

The very detailed order of operation provided for the SLC raiders to choose battleships as their priority target, with aircraft carriers as their second choice, followed in order of precedence by the floating dock and cruisers. The SLC warheads, weighing 225 kg each, had to be adjusted to explode after two hours. Each raider would be provided with £10. Once their mission was accomplished, the crews of the SLCs were to destroy their vessels, if possible, near one of the French warships interned in Alexandria since the surrender of France, then board these ships and declare themselves officers of the Regia Marina in permanent effective service (for this purpose they would have to be provided with the identification card), refraining from saying anything else about their mission. To maintain contact with Supermarina, Gondar would have used the special code ‘G’.

On Gondar were then embarked the three SLCs destined to force the port of Alessandria and their crews, each composed of two men: the first was formed by the lieutenant Alberto Branzini and the ensign Alberto Cacioppo, the second by the captain of the Naval Engineers Elios Toschi (who, with his colleague and friend Teseo Tesei, had been the inventor of the slow-moving torpedo) and by the diver sergeant Umberto Ragnati, the third by Naval Weapons Captain Gustavo Stefanini and Diver Sergeant Alessandro Scappino. The three SLCs were loaded in La Spezia (where they were immediately placed in the container cylinders), while the crews would board in Messina, where Gondar arrived at 09:00 PM on September 23rd, after leaving La Spezia on the night of the 21st.

In addition to the six men who formed the crews of the SLCs, Commander Giorgini himself went up to Gondar in Messina, as head of the mission, and three reserve operators, in charge of replacing the men of the SLCs in case of need. They were Ensign Aristide Calcagno, Sergeant Diver Giovanni Lazzaroni and Chief Electrician Second Class Cipriano Cipriani.

Toschi and Lazzaroni were veterans of the failed operation of the “G.A. 1”, in which, shipwrecked after the sinking of the Iride, they had helped to save some sailors trapped in the wreck of the submarine.

After disembarking part of the secret archive and replenishing its supplies of fuel and water at night, Gondar set sail from Messina at 07.30 AM on September 24th, 1940, bound for Alessandria. It was planned for the submarine to reach a predetermined point, called “D”, to check that everything was quiet on the surface. If that verification was successful, it would then have continued to a second conventional point, ‘A’, where the SLCs would be released, which would then enter the port of Alexandria. The navigation approaching the target, which took place at night on the surface and during the day submerged to avoid being spotted, was not characterized by any significant events. Several ships were sighted, none of which, however, sighted the Italian boat.

Gondar arrived off the coast of Egypt on the night of September28th-29th, as planned, but the situation was far from calm: a British corvette was sighted, which forced the submarine to dive. After a couple of hours, Gondar resurfaced, with no more ships in sight.

On the night between the 28th and the 29th, the boat had to dive again. Hydrophones reported the noise of at least three turbine-driven ships sailing nearby, and later also the sounds of the engines of other ships moving away. Numerous ships were sighted, at distances between 500 and 2,000 meters: on board it was not known, but it was the Mediterranean Fleet, which went out to sea for operation “MB. 5».

Around 07:00 PM on the 29th, with some delay (but not enough to prevent the SLCs from being released for the attack on the port), Gondar emerged only six miles (for another source, 22 miles) from Alexandria, also to change air and recharge the batteries, but after a few minutes he was reached by a message from Supermarina, ordering Gondar to reach Tobruk and then await further orders.

This was because Supermarina had been informed, while Gondar was sailing towards Alexandria, that the entire Mediterranean Fleet (battleships H.M.S. Valiant and H.M.S. Warspite, aircraft carriers H.M.S. Illustrious, cruisers H.M.S. York, H.M.S. Sydney and H.M.S. Orion and destroyers H.M.S. Hyperion, H.M.S. Hero, H.M.S. Hereward, H.M.S. Imperial, H.M.S. Ilex, H.M.S. Jervis, H.M.S. Juno, H.M.S. Janus, H.M.S. Mohawk, H.M.S. Nubian and H.M.S. Stuart) had left Alexandria on the 28th to provide support for an attempt to reinforce the garrison of Malta by sending 2,000 men embarked on the cruisers H.M.S. Liverpool and H.M.S. Gloucester; the aforementioned operation “MB. 5». Alexandria had no battleships, aircraft carriers or cruisers left: no valuable targets, and Gondar’s mission had become useless. At 01.55 PM Supermarina had therefore sent the message PAPA ( (Absolute Precedence over Absolute Precedence) no. 28644 to the Naval Command of Tobruk, in which the latter was informed that Gondar had been ordered to reach this base. Marina Tobruk was to inform Commander Giorgini that Operation “G.A. 2” was postponed due to the sudden departure of the main forces, and that Gondar should be ready to leave as soon as the Mediterranean Fleet returned to port.

But the submarine, sailing submerged, had not been able to receive the message until the last moment, when it had surfaced, on the evening of the 29th.

Having received the message, Gondar changed course to reach Tobruk, continuing to recharge its batteries, but at about 20.30 it sighted an enemy ship (according to another source, two) starboard in the bow, at a distance of one and a half kilometers, sailing alongside: it was the Australian destroyer H.M.A.S. Stuart, under the command of the Lieutenant Commander Norman Joseph MacDonald Teacher (who was normally the navigation officer and had just assumed command of the ship – which was supposed to reach Malta for work – replacing the actual commander, Lieutenant Captain Robinson, who fell ill). H.M.A.S. Stuart, which went out to sea for operation “MB. 5” with the rest of the Mediterranean Fleet, was now returning to Alexandria at 10 knots due to boiler failures (a steam pipe had burst), taking advantage of this to conduct anti-submarine rakes with sonar. The Italian boat immediately dove to a depth of 80 meters, 110 miles by 300° from the lighthouse of Alessandria (i.e., northwest of that base, as well as north of Sollum). On board they arranged for the silent trim, stopping the engines and any other machinery, but shortly afterwards H.M.A.S. Stuart’s Asdic (which, according to one version, had spotted it from the bridge before it dove) spotted it, and the hunt began.

According to an article by Alan Payne and L. J. Lind in the June 1977 Naval Historical Review, it was at 10:15 PM that H.M.A.S. Stuart made contact with Asdic, namely that a submarine, starboard forward 2,700 yards away, was slowly crossing its course from starboard to port. Second Lieutenants J. G. Griffin and T. S. Cree (the latter was the officer in charge of Asdic) and Petty Officers Ronald A. H. MacDonald and L. T. Pike were on sonar duty; The contact was very sharp.

On the submarine Gondar, Brunetti understood from the hydrophones that the submarine had been discovered.

At 10:20 PM (according to Italian sources, 15 minutes after the submarine had submerged) H.M.A.S. Stuart sailed up the course of Gondar and launched a first package of six depth charges, at the same time throwing a calcium fire into the water to illuminate the surface of the sea and facilitate the sighting of any wreckage or fuel slicks.

Aboard Gondar, the explosion of the first depth charges (which, according to a source, occurred while the immersion maneuver was still in progress) knocked out the depth gauges, blew out the lights, and caused the cylinder-containers of the SLCs to flood.

More bomb discharges followed, once an hour (between four and six bombs per discharge), intermittently but regularly. After the first attack, H.M.A.S. Stuart regained contact aft to port, 1,370 yards away, but a defect in the Asdic apparatus made it difficult to maintain contact; fearing that this might cause him to escape his prey, Teacher contacted Alexandria and asked for some other units to be sent to help. A second destroyer, H.M.S. Diamond departed from Alexandria. According to Italian sources, the vessel arrived on the spot at 10.30 PM, together with a “corvette”, but according to British sources, in reality, H.M.S. Diamond arrived on the spot at the end of the hunt, when Gondar was already sinking (or even later), and it was only H.M.S. Stuart that conducted the hunt during the night, even if on Gondar there was the impression (from the hydrophones) of being hunted by three ships, two of which came later.

At 10:45 PM Lieutenant Cree of H.M.A.S. Stuart reported the position of the target to the bridge, and the destroyer reduced speed to 12 knots, dropped five more depth charges, and fired another charge into the sea, but again no wreckage or fuel was sighted. The effect of this second attack, however, was devastating: the bombs exploded under the submarine, damaging various instruments, other pressure gauges and a fuel tank (which began to leak) and disabling the Gondar’s air purification apparatus, thus reducing the maximum time the submarine could stay submerged. Then, water started seeping into the aft area.

Between attacks, H.M.A.S. Stuart began to cross over the vertical of the Gondar, continuously executing mock attacks at high speed, to unnerve the submarine’s crew. It was probably this set of maneuvers that convinced the men of Gondar that not one, but three enemy ships were hunting them.

At one o’clock in the morning of the 30th, H.M.A.S. Stuart circled the submerged submarine, at a distance of between 1,370 and 18,30 meters, to ascertain its position, then launched a third discharge of depth charges; The fourth discharge followed at four o’clock in the morning, the fifth at 5.30 AM. Between 5:30 and 6:25 AM., H.M.A.S. Stuart carried out a series of mock attacks for demoralizing purposes, then carried out a final bomb drop at 6:25 AM. The first light of day revealed small fuel slicks to the Australian crew, indicating that the submarine had been damaged.

Within a few hours, about fifty depth charges were dropped, all of which exploded very close to Gondar. The crew of the submarine, gathered in small groups of four or five men, could do nothing but listen to the sound of the ship coming and going (or rather, of the ships, since they seemed to be three) and waiting in silence and semi-darkness for the bombs to explode, hoping that they were not too close. It was hot, there was no air, and the floor was strewn with fuel leaking from a damaged tank. Each time the submarine was violently shaken by the explosions, the bulkheads threatened to give way. The night seemed to go on forever.

The concussions caused by the detonations of the bombs also caused various water infiltrations, and gradually knocked out the Gondar’s equipment.

The chief engineer, Lieutenant of the Naval Engineers Vincenzo Cicirello, examined the apparatus for air purification and tried to fix it, but without success. He reported the situation to Commander Brunetti, who shook his head and ordered some air to be released, in the hope of improving the internal situation a little, but nothing changed.

After six hours of immobility, Commander Brunetti made an attempt to get away and escape, correcting his depth from time to time, but the “characteristic noise like a whip, similar to that produced by lead pellets falling on a metal sheet” persisted. The sign that the enemy’s Asdic did not let go. (According to another version, in the interval between two bomb drops, Gondar managed to get away, but, when he thought, he had probably managed to disengage from the enemy, he was again located and bombarded with other depth charges, very well centered).

At a certain point, probably because of the damage suffered, Gondar began to rise involuntarily in depth, reaching a depth of 40 meters. This allowed depth charge discharges to have even more devastating effects.

Five minutes after the water raised by H.M.A.S. Stuart’s last bomb blast (at 6:25 AM) had subsided, the anti-submarine seaplane Short Sunderland Mk I number L2166 (the “U” aircraft of the 230th Squadron of the Royal Air Force), piloted by Captain P. H. Alington and Lieutenant Brand, also arrived from the south. Taking off from Alexandria at 5.30 AM, once on the spot (indicated by the pilot as 31°35′ N and 28°43′ E) the plane circled H.M.A.S. Stuart, made a light signal of recognition and then began to fly over the sea at low altitude, in search of the submarine. An hour later (according to another source, at seven o’clock in the morning), as if that were not enough, the anti-submarine trawler H.M.S. Sindonis also arrived on the scene and joined the hunt.

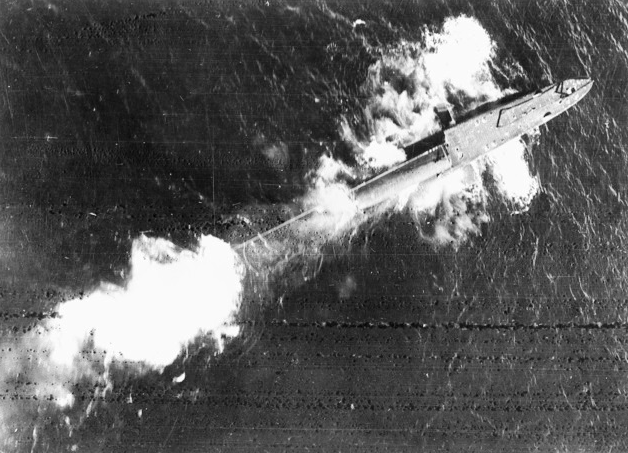

The Gondar photographed by the crew of the Sunderland

(Imperial War Museum)

Gondar tried in every way to evade the chase, but after hours and hours of bombardment the damage became too serious to be able to hope to survive much longer. The efforts of the chief engineer Cicirello were no longer enough to repair the damage. At seven o’clock, a bomb exploded very close to Gondar and caused a violent change in depth. To counteract the waterways, the internal pressure had been raised to three atmospheres, almost exhausting the available reserve.

It was interesting to note a significant discrepancy between the British and Australian sources. According to Australian Navy sources, while this was happening, H.M.A.S. Stuart meanwhile kept the sonar contact with the submarine, which it never lost, until it emerged. According to Normak Franks’ book “Search, find and kill”, dedicated to the RAF’s successes in anti-submarine warfare, H.M.A.S. Stuart had lost contact when Alington’s Sunderland arrived on the scene. It was the seaplane that found the boat, when the crew spotted air bubbles surfacing a couple of miles from the destroyer. At this point Sunderland dropped a depth charge on the bubble sighted. The crew then spotted another bubble and dropped a second bomb on it, but this time the device did not explode. A third bomb exploded, and this time Gondar had to emerge.

According to Australian sources, at 8:20 AM (9:20 AM H.M.A.S. Stuart time) the Sunderland dropped a cluster of bombs about 2,700 meters deep forward of the Stuart.

In any case, around 8.30 AM Gondar began to take on water more copiously, while it was now impossible to maintain depth. Compressed air reserve was reduced to 30 kg/cm2, the minimum for attempting to surface. Commander Giorgini conferred with the officers and then, believing that the situation was now unbearable and that remaining submerged would have meant sinking at any moment with the total loss of the crew, he ordered Commander Brunetti to surface, abandon, and sink the boat by itself. Giorgini ordered Brunetti not to attempt an attack or launch torpedoes unless the submarine was in a suitable position to launch at the time of coming to the surface. So, it was done. The men put on their life jackets, and at 8.40 AM Commander Brunetti had the diving tank and the double central bottoms blown.

(A source, probably erroneous, gives a rather different version: at eight o’clock in the morning Gondar began to sink uncontrollably due to the damage suffered, so all the tanks were blown to stop the sinking; the submarine stopped at a depth of 155 meters, but then began to rise uncontrollably, with increasing speed, until it came to the surface).

According to some British sources, during the surfacing maneuver the Sunderland dropped a bomb on the air bubble from an altitude of 210 meters that signaled that the submarine was about to surface. This caused Gondar to lose control, which was at that time at a depth of about twenty meters, and which sank again to a depth of 90 meters, and then resumed the surfacing maneuver when all the tanks were blown.

Rising rapidly to the surface, at a speed of about 10 knots, the battered Gondar resurfaced one last time right in the middle of the enemy ships. Her bow came to the surface only 730 meters from the bow of H.M.A.S. Stuart. It was 9:20 AM, 11 hours had passed since the first depth charge attack.

H.M.A.S. Stuart immediately opened fire with all the guns, fortunately not very accurate (the destroyer was estimated to have passed the conning tower from side to side with a cannonade, while others fell all around the submarine), while H.M.S. Sindonis maneuvered to get closer, the Sunderland dropped one or perhaps three bombs, which exploded close to the submarine (Brunetti, in his report, spoke of two bombs, dropped from the Sunderland from about 50 meters above sea level, while the crew was abandoning the unit; they exploded about ten meters forward to port).

The Gondar sinking

(Australian War Memorial)

Gondar’s navigation officer, Ensign Giuseppe Dell’Oro, was instructed by Commander Brunetti to throw the box containing the secret publications into the sea, to prevent them from falling into enemy hands. When he opened the hatch to be among the first, the strong pressure inside the submarine, much higher than the external one, threw him into the air, causing him to fall back on deck, wounded. After him, the men began to escape through the hatches of the bow and conning tower, jumping into the water.

On H.M.A.S. Stuart, after firing the first salvo, it was seen that the crew of Gondar was abandoning the unit, so firing ceased, and Commander Teacher ordered a dingy to be put to sea. The distance between the two units was just over 900 meters; some of the Italian sailors swam all the way aboard H.M.A.S. Stuart, while others were picked up by the dingy. They were soaked, dirty, and exhausted.

Commander Francesco Brunetti (in this picture already promoted to Captain)

(Giovanni Pinna Collection)

When almost the entire crew had thrown themselves into the sea, Commander Brunetti and some other men, including sailor electrician Luigi Longobardi, went down to the maneuvering room, opened the air vents of the surface, the double central bottoms and the rapid, to sink the submarine (according to some sources, they also activated a dozen explosive charges for self-destruction), and then, having climbed back into the conning tower, they left the boat last (according to another version, Brunetti, after opening the Kingstone, climbed into the conning tower and waited for the submarine to sink under him, until he found himself in the water). Captain Giorgini made one last lap to check that there was no one left on board, then jumped into the sea.

Electrician Luigi Longobardi

(Giovanni Pinna Collection)

Captain Teacher of H.M.A.S. Stuart had hoped to capture Gondar intact and tow it to Alexandria, but when the dingy moved to the side of the dying submarine, her occupants realized that the scuttling procedures had been initiated. Explosive charges exploded shortly after the last man had left the boat. Gradually but rapidly, Gondar settled and slid beneath the waves at 32°02′ N and 27°54′ E (according to Italian sources) or 31°33′ N and 28°33′ E (according to British sources; a dozen miles off Marsa Matruh, and 25 miles off El Daba), in water more than 2,000 meters deep. The bow of the submarine remained above the surface for five or ten minutes, before finally disappearing into the abyss. It was 9:25 AM (9:50 AM for another source) on September 30th, 1940.

The Sunderland, after flying over the sinking boat taking several photos, returned to its base, where it arrived at 10.30 AM.

H.M.A.S. Stuart rescuing some of the crewmembers of the Gondar photographed from the Sunderland

The Italian crew and raiders were rescued and taken prisoner by the British units. H.M.A.S. Stuart recovered 28 men, including Brunetti, Giorgini, Cicirello and a second lieutenant, while another 19 survivors, including Toschi, were recovered by the H.M.S. Sindonis.

Signaller L. E. Clifford later recalled that one of the survivors, while boarding H.M.A.S. Stuart, saw an Australian sailor armed with a rifle with a bayonet and shouted, “No kill”, misunderstanding the meaning of that presence. Commander Brunetti, who spoke fairly good English, stated that he had been forced to surface because the bombs had destroyed the air purification apparatus, it had not been possible to repair it, and the air had become unbreathable.

There was only one victim, the Neapolitan sailor Luigi Longobardi. Lingering on board, with the commander Brunetti and a few others, to provide for the sinking, he threw himself into the sea among the very last one and was probably killed at sea by the explosion of an airplane bomb. He was decorated with the Gold Medal for Military Valor, in memory.

(Strangely, British sources speak of two casualties among the crew of the Gondar, one of whom would have drowned and the other killed by a bomb from Sunderland: but the only one who fell among the crew of the submarine would have been Luigi Longobardi).

The sinking of Gondar was a hard blow for the young I Flotilla MAS: in one fell swoop a submarine SLC carrier, three SLCs, as many trained and capable crews and the commander of the flotilla himself had been lost.

As a result of the loss of the Gondar, moreover, the veil of secrecy that covered the assault craft employed by the 1st MAS Flotilla began to crack. When the submarine surfaced before sinking, in fact, British ships and planes did not fail to notice the unusual cylinders on its deck. The presence on the submarine of so many officers and divers also aroused many suspicions. Upon their arrival in Alexandria, the survivors were immediately interrogated, especially Giorgini, the highest ranking (who on H.M.A.S. Stuart had passed himself off, apparently successfully, as a destroyer commander embarked on Gondar as a passenger). The questions focused mainly on the cylinders and the presence of officers and divers. Giorgini did not answer, but a British Naval Intelligence officer surprised him when he asked him if he was the commander of the I Flotilla MAS based in La Spezia, and if, on the coast between La Spezia and Livorno, officers and non-commissioned officers were trained who would then have to attack British ports and naval bases in the Mediterranean.

According to the aforementioned article by Payne and Lind in the June 1977 Naval Historical Review, it was the commander of the Gondar, questioned by Teacher, who “broke down in tears” and revealed that the submarine was carrying three “human torpedoes” for an attack on the ship in the port of Alexandria.

One way or another, the British already knew something about the Flotilla’s activities, but this would not allow them to stop the attacks on Alexandria, Suda, Gibraltar and Algiers that would be launched in the years to come, once the Flotilla, having recovered from its initial losses and drawing on past experiences, had refined its methods.

On arrival in Alexandria, H.M.A.S. Stuart was given a hero’s welcome, especially – in very colorful terms – by the other units of the Australian destroyer flotilla (H.M.A.S. Vampire, H.M.A.S. Vendetta and H.M.A.S. Waterhen). Admiral Andrew Browne Cunningham, commander of the Mediterranean Fleet, reported it to the fleet as “an outstanding example of a result obtained through patience and skill in the use of the Asdic (sonar) apparatus”. The commander of H.M.A.S. Stuart was decorated with the Distinguished Service Order for the sinking of the Gondar, while the sonar officers (Second Lieutenants J. G. Griffin and T. S. Cree and Petty Officers Ronald A. H. MacDonald and L. T. Pike) received the Distinguished Service Cross (the two officers) and the Distinguished Service Medal (the two non-commissioned officers).

The men of Gondar first ended up in the prison camp of Geneifa, Egypt, where the survivors of the submarines Berillo, Rubino, Galvani and Uebi Scebeli and other units sunk during the summer of 1940 were already located; later they were transferred to various prison camps in India.

Not everyone resigned themselves to spending the rest of the war behind a fence. Elios Toschi, in particular, after passing through the camps of Ahmednagar and Ramgarh, ended up in Yol, a camp reserved for prisoners who had already tried several times to escape. From there Toschi escaped together with the Lieutenant Commander Camillo Milesi Ferretti, former commander of the submarine Berillo. Their paths diverged and Toschi, who had attempted to cross the Himalayas to try to return to Italy, was recaptured. Fleeing again, Toschi finally took refuge in neutral Portuguese India.

Captain Naval Weapons Gustavo Stefanini, future managing director of OTO Melara, remained a prisoner in Bangalore until 1946; Commander Giorgini also remained in captivity until April 1946, while Commander Brunetti was repatriated in 1944, during the co-belligerence.

After the war, Stefanini returned to the Italian defense industrial scene, becoming CEO of OTO Melara.

He was the ‘father’ of the 76mm gun mount, the most prolific and successful naval gun mount of modern times.

(Naval Historical Society of Australia)

The motivation for the Gold Medal for Military Valor awarded to the memory of the electrician sailor Luigi Longobardi, born in Lettere (NA) on April 22, 1920:

“An electrician embarked on a submarine attacked with depth charges by three enemy ships and an aircraft for twelve consecutive hours, he worked tirelessly in carrying out the tasks entrusted to him with skill and determination. When it became necessary to emerge in order to scuttle the submarine that had been unused by the explosions of the bombs, he gave proof of exceptional courage and a deep sense of duty, remaining at his post until the last possible possibilities in order to contribute to the salvation of the Unit. Throwing himself into the sea in his last moments, he was hit by the explosion of bombs dropped from an airplane and sacrificed his young life for an extreme ideal of his homeland that had kept him on the ship beyond his duty. Eastern Mediterranean, 30 September 1940.”

The motivation for the Silver Medal for Military Valor awarded to Lieutenant Francesco Brunetti, born in La Spezia on November 20, 1909:

“Commander of a submarine destined to carry out the offensive with special means to an armed enemy naval base, he was attacked with depth charges by three ships and an aircraft for twelve consecutive hours. In difficult conditions due to continuous serious damage suffered by the submarine, he tried by every means to escape the persistent enemy chase until every further attempt at resistance was frustrated, he did his utmost and arranged for the crew to abandon the submarine in a disciplined and rapid manner. Oblivious to the artillery fire and the throwing of bombs by the unit, which it abandoned only when the force of the sea tore it from the bridge. An example of cold blood, skill and a high sense of duty.”

The motivation for the Silver Medal for Military Valor awarded to Lieutenant Vincenzo Cicirello of the Naval Engineers Machinery Directorate:

“Chief Engineer of a submarine attacked with depth charges by three enemy ships and an aircraft for twelve consecutive hours, in difficult environmental conditions due to continuous serious failures reported by the unit, he worked tirelessly to repair the failures themselves and effectively assisted the commander in prolonging the submarine’s resistance as much as possible. He left the unit only at the command of the commander, showing a cool head, a spirit of sacrifice and a high sense of duty.”

The motivation for the Silver Medal for Military Valor awarded to Ensign Giuseppe Dell’Oro:

“A course officer of submarines attacked with depth charges… he worked tirelessly to ensure the smooth running of his service. Having been ordered to be one of the first to abandon the unit to throw the box of secret publications into the sea, he managed to carry out the order, despite the fact that when he came out of the hatch he was thrown onto the deck by the strong internal pressure, being injured.”

The motivation for the Silver Medal for Military Valour awarded to frigate captain Mario Giorgini, born in Massa Carrara on March 19, 1900:

“Embarked on a submarine as the leader of an expedition of assault vehicles destined for a risky mission against an enemy base, he gave the commander of the unit, subjected to a long and exhausting hunt by three ships and an aircraft, the solid support dictated by his valid experience and his indomitable courage. After 12 hours of hunting, the unit emerged due to irreparable damage, and ordered its rapid sinking in order to ensure that the disappearance of the hull also that of the treacherous vehicles embarked. As the unit began to sink, he entered the interior rooms to personally supervise the complete evacuation of the crew. An example of serene bravery and of the highest military virtues.”

Original Italian text by Lorenzo Colombo adapted and translated by Cristiano D’Adamo

Operational Records

| Type | Patrols (Med.) | Patrols (Other) | NM Surface | NM Sub. | Days at Sea | NM/Day | Average Speed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Submarine – Coastal | 4 | 3440 | 534 | 33 | 120.42 | 5.02 |

Actions

| Date | Time | Captain | Area | Coordinates | Convoy | Weapon | Result | Ship | Type | Tonns | Flag |

Crew Members Lost

| Last Name | First Name | Rank | Italian Rank | Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Longobardi | Luigi | Electrician | Elettricista | 9/30/1940 |