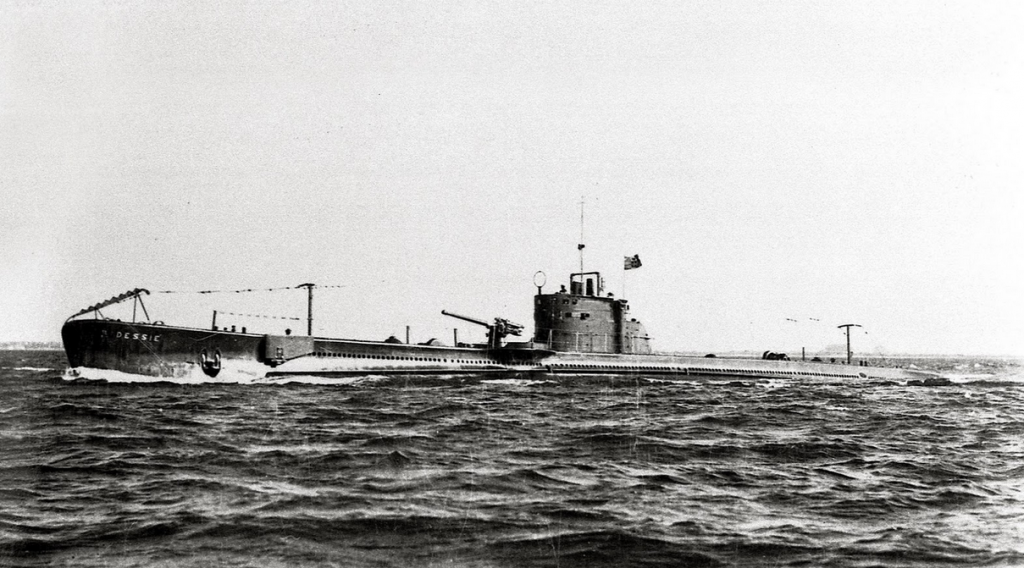

The submarine Dessiè was an Adwa-class coastal submarine (698 tons displacement on the surface and 866 tons submerged).

The boat completed 27 missions of various types (18 patrols, 1 transport, and 8 transfers), covering a total of 15,193 miles on the surface and 4,263 submerged.

The launch of the submarine Dessiè from a real of the ‘Istituto Luce’

Brief and partial chronology

April 20th, 1936

Setting up at the Franco Tosi shipyards in Taranto.

November 20th, 1936

Launched at the Franco Tosi shipyard in Taranto.

Dessiè, and the twin boat Dagabur, on the slip in Taranto

April 14, 1937

Entry into service. Dessiè was assigned to the XLIII Submarine Squadron, based in Taranto.

The early captains were Lieutenant Gino Birindelli, and later Primo Longobardo, both future M.O.V.M. (Gold Medal for Valor). Birindelli would also reach the top rank in the Navy in the 70s.

August 20th, 1937

Under the command of Lieutenant Mario Muro, Dessiè sailed from Leros to participate in the Spanish Civil War as part of a clandestine mission in the Aegean Sea against the traffic of supplies for the Spanish Republican forces.

August 29th, 1937

The boat returned to Leros, ending the mission without having reaped any results.

1938

Located in Tobruk.

Dessiè in 1938

1940

Transferred to Taranto and later to Augusta.

June 10th, 1940

When Italy entered the war, Dessiè (Lieutenant Commander Fausto Sestini) was part of the XLVI Submarine Squadron (IV Grupsom of Taranto), along with the twin boats Dagabur, Uarsciek and Uebi Scebeli.

August 8th, 1940

Sent on patrol southwest of Crete, between the parallel of Gaudo, the coast of Crete and the meridian of Cerigotto. It was the first war patrol under the command of Lieutenant Commander Fausto Sestini.

August 13th, 1940

In the evening, the crew sighted a fast steamer heading east and chased it on the surface, but was unable to complete the attack maneuver, because the merchant took advantage of its higher speed to escape.

August 16th, 1940

The boat concludes the mission, returning to base.

October 28th, 1940

The boat was among the submarines sent to form a barrier between the Ionian Sea and the Aegean Sea. Even though the Mediterranean Fleet (which operates in that area, going as far west as the Ionian Islands) had gone out to sea, Dessiè, sent south of Crete, did not see anything: the barrier it forms with three other boats (Luigi Settembrini, Ciro Menotti, Tricheco) was in fact too wide.

November 25th, 1940

Dessiè (Lieutenant Adriano Pini) was sent off the coast of Malta to participate in the fight against the British operation “Collar” (transfer of ships from Alexandria to Gibraltar, dispatch of convoys with supplies from Gibraltar to Malta and the ports of the Levant, all with the help of Force H and the Mediterranean Fleet: the inconclusive battle of Cape Teulada would be the result).

November 28th, 1940

At 3.02 AM Dessiè, lying in ambush 50 miles east/southeast of Pantelleria (and west of Malta), sighted in position 36°30′ N and 12°59′ E three major units proceeding in a line with an estimated course of 270° (westward) and speed 20 knots: it was the British 3rd Cruiser Squadron, with the heavy cruiser H.M.S. York and the light cruisers H.M.S. Glasgow and H.M.S. Gloucester, at sea as part of British convoy traffic in connection with Operation Collar. At 3:05 AM the submarine launched two torpedoes from the aft tubes, from a distance of 3,500 meters, against the middle ship (H.M.S. Glasgow), then disengaged in diving. Two loud explosions were heard and then a violent explosion, however, no ship was hit.

December 16th through 25th, 1940

The boat was sent to patrol, along with the submarines Fratelli Bandiera and Serpente, in the waters around Malta.

January 1941

Unsuccessful ambush off the coast of Derna.

May 20th, 1941

Sent to lie in wait between Crete, Alexandria and Sollum, along with numerous other submarines, in support of the German invasion of Crete (Operation “Merkur”).

July 21st and 22nd, 1941

Sent between Pantelleria and Malta, together with three other submarines (Fratelli Bandiera, Luciano Manara and Ruggero Settimo; the boats were deployed twenty miles from each other), in contrast to the British operation “Substance”, consisting in sending to Malta a convoy of supplies – six cargo ships and a troop transport – escorted by the battleship H.M.S. Nelson, the light cruisers H.M.S. Edinburgh, H.M.S. Manchester and H.M.S. Arethusa and 11 destroyers, and at the same time the return from Malta of six unloaded merchant ships and the military tanker Breconshire, escorted by the destroyer Encounter. Force H, which went out to sea with the battlecruiser H.M.S. Renown, the aircraft carrier H.M.S. Ark Royal, the light cruiser H.M.S. Hermione and six destroyers, provided cover for the operation, while units of the Mediterranean Fleet from Haifa and Alexandria carried out diversionary actions. Dessiè did not spot the British convoy.

January 3rd, 1942

Sent to lie in wait south of Malta (the ambush began at noon on January 3rd), in the area between the meridians 23°20′ E and 23°40′ E and the parallels 33°00′ N and 33°40′ N, with the task of sighting and attacking any British naval forces that might take to the sea to oppose Operation “M. 43”, consisting of sending a large convoy of supplies to Libya. Such a threat would not manifest itself.

June 11th, 1942

The boat was sent, together with four other submarines (Onice, Ascianghi, Aradam and Corallo) to ambush in the triangle between Malta, Pantelleria and Lampedusa in contrast to the British operation “Harpoon” (a heavily escorted convoy from Gibraltar to Malta), as part of the Battle of Mid-June. However, Dessiè did not see any ships.

July 15th, 1942

The submarine Dessiè, along with other submarines, was sent to lie in wait between La Galite, the Isle of Dogs, Cape Bon, and Cape Kelibia to intercept the British fast minelayer H.M.S. Welshman, bound for Malta with urgent supplies. The boat did not spot British unity.

August 11th, 1942

Under the command of Lieutenant Renato Scandola, Dessiè departed from Trapani bound for a sector north of the Gulf of Tunis, to participate in the fight against the British convoy “Pedestal” bound for Malta, an operation that would lead to the largest air-naval battle of the Mediterranean war, the Battle of Mid-August. Dessiè, along with Otaria, Dandolo, Emo, Avorio, Cobalto, Alagi, Ascianghi, Axum and Bronzo, forms a barrage of ten submarines north of Tunisia, between the meridians of the Scogli Fratelli and the Banco Skerki (from the waters east of La Galite to the approaches of the Strait of Sicily), constituting a barrier line of the western entrance of the Strait of Sicily, north of the La Galite-Banco Skerki junction. The orders were to act with great offensive determination, launching as many torpedoes as possible against any target, merchant, or military, larger than a destroyer. The specific Dessiè ambush area was located 80 miles north of Tunisia, in the Skerki Bank channel.

August 12th, 1942

At 5.22 AM Dessiè dove, entering the assigned area.

At 6:07 PM, a hydrophone picked up an indistinct noise on a 270° bearing, but observation on the periscope revealed nothing. The submarine then maneuvered to get closer to the source of the noise, the rotation of which gave Commander Scandola the impression that it was falling slightly towards the coast. Dessiè took a course perpendicular to the survey, and at 7:00 PM it sighted the treetops and the smoke emitted by the ships of the convoy on the periscope (according to a source, Dessiè would have been guided towards the convoy also by the smoke of the fires of the aircraft carrier H.M.S. Indomitable, severely damaged by Axis air attacks).

At 7:07 PM, Dessiè observed an attack by Italian planes against the convoy, whose ships proceeded in scattered order, zigzagging under the protection of destroyers. At 7:10 PM, Scandola counted 24 ships on the periscope: 14 merchant ships and 10 destroyers. Several large merchant ships were forming a compact nucleus (with a true course of 110° and an estimated speed of 15 knots), while some others continued in scattered order. Three destroyers crossed forward of the larger group, and two others defended the port side towards the stern. Two other destroyers, further north, keep Dessiè on about zero beta.

The sea was very calm, the sun low on the horizon. Dessiè was on an attack course due to an impact of 110°, and at 7.38 PM (in position 37°38′ N and 10°25′ E, 45 miles northwest of Cape Bon), from an estimated distance of 1800 meters, launched at intervals of three seconds the four torpedoes of the forward tubes, with a divergence of two degrees between one and the other. The target was a group of eight large merchant ships (estimated tonnage 10,000-15,000 GRT) very close to each other (to the point that the bow of some “covers” the stern of others), with modern lines (slender bow and cruiser stern) and propelled by turbines.

After launching, Dessiè involuntarily surfaces with the conning tower. Scandola ordered a dive to a depth of 40 meters, and as this happened, the detonations of two torpedoes were heard 1 minute and 40 seconds after the first launch. Continuous explosions could be heard on the hydrophones, which made it impossible to understand if any ship had stopped. Commander Scandola then decided to return to periscope depth, to attack other ships, if possible, with torpedoes from the stern tubes.

At 7:56 PM, while Dessiè was going up, the counterattack of the escort began. Three enemy units, equipped with sonar and probably hydrophones, launch about 120 depth charges in the space of an hour and a half. None, however, exploded close enough to cause damage to the submarine, which was stationary at 90 meters, in silent trim. With each restart of the engines, the hunt resumes with greater intensity.

At 9:20 PM the drops became weaker until they disappeared, and at 9:27 PM the anti-submarine hunt was finally over. Commander Scandola had the impression that the launch of the torpedoes has achieved results, because the counterattack came only after twenty minutes and two of the enemy destroyers always kept in the same sector (the one where Scandola thinks the affected merchant ships were located), moving away from it only to launch the depth charges.

The outcome of the launch of Dessiè is, to this day, still the subject of a debate. Several historians believe it was likely that it was one of its torpedoes that hit the large British motor ship Brisbane Star, of 12,791 GRT, which suffered serious damage (initially immobilized, it soon managed to start up again; a few hours later it was hit by a second torpedo, launched by an aircraft) but it was one of the few merchant ships in the convoy to be able to reach Malta. Some also believe that one or more torpedoes from Dessiè sank the British motor ship Deucalion, of 7516 GRT (which sank in position 37°38′ N and 10°25′ E, five miles east of the Isle of Dogs and 39 miles northeast of Bizerte), already damaged by German air attacks. However, the careful research of the historian Francesco Mattesini, as well as most historians, credits the sinking of the Deucalion to the action of German Heinkel He 111 torpedo bombers alone. Since the moment of the attack of Dessiè also coincided with that of an Italian-German air attack, with torpedo launched by Italian Savoia Marchetti SM aircraft. 79 “Sparviero” and German Junkers Ju 88 and Heinkel He 111, there was also no absolute certainty as to whether the Brisbane Star was hit by a torpedo from Dessiè, rather than by one of the torpedo bombers.

At 10:12 PM, Dessiè came to the surface. At the stern, about a mile and a half distant, two steamers were visible, burned, and near them a dense black cloud in which flashes could be seen, which was believed to be a third steamer, also on fire. The violence of the fires on the steamers leads Scandola to believe that they were all already condemned. In need of the charge of air and electricity, Scandola decided to leave and return to the site as soon as possible. At 11.50 PM the steamer exploded in the cloud of smoke, hit by torpedoes; with flames blazing even more violently.

August 13th, 1942

At 3:15 AM the last flames of the three steamers were extinguished. Dessiè headed towards this area, crossing the sea strewn with naphtha and wreckage. At 5:36 AM the boat dove, and at 10:47 AM received an encrypted message (064113) ordering the captain to emerge and go to his mopping up area, which he did. At 11:59 AM, three bombers were sighted heading west and 10 km away, flying at an altitude of about 200 meters, thus a crash dive was ordered. An hour later, Dessiè resurfaced, and then dove again with a crash dive at 2.27 PM. At 3.22 PM, the boat returned to the surface, but at 3.37 PM crash-dove again due to the sighting of an aircraft. At 4:12 PM Dessiè came to the surface once again, and after three minutes sighted an immense column of smoke to the south, a sign of a burning ship. At 4:26 PM, two planes were also spotted circling the fire, and at 5:08 PM Dessiè headed in that direction. Aircraft of the Regia Aeronautica and the Luftwaffe continuously flew over the submarine, which exchanged recognition signals with them. At 5:14 PM, Dessiè spotted some boats in the vicinity of the fire. At 5:30 PM, as the fire continues, Scandola concludes that the ship had probably sunk.

At 5:56 PM, another sighting of planes forced Dessiè to dive once again until 6:48 PM, when the boat resurfaced and headed towards the wrecks, to look for something that would allow the identity of the sunken ship to be traced. At 7:20 PM, the submarine went under a lifeboat, but it was empty, as were the nearby boats. However, some objects were recovered, to trace the name of the ship. At 7.30 PM Dessiè moved away at full speed, while the flames floating on the sea were extinguished.

At 7:35 PM, the submarine sighted formations of German bombers, dropping bombs near the fire. The crew lighted two recognition flares and unfurled a second magnitude (large) Italian flag on the bridge, but the bombers – a dozen of them – attack Dessiè anyway. The first, a discharge of bombs fell into the sea forward of the submarine, the subsequent ones frame it from the side. Commander Scandola, three other officers, two non-commissioned officers and two sailors were injured by shrapnel from the bombs, which also caused various damage to the unit. One of the injured, the 23-year-old sailor Antonio Fontana from Syracuse, died on board Dessiè the following day, August 14th, from the severity of his injuries.

At 7:38 PM, after the flagship aircraft had made a reconnaissance tour over the bridge of Dessiè, the bombers left. At 7.40 PM the verification of the damage suffered began (the bombs of the planes caused several failures to the hull and to the on-board equipment, breaking among other things some elements of the accumulator batteries, and thus causing acid leaks), meanwhile taking course for the north-eastern end of the assigned sector. Maricosom was asked to send a torpedo boat to transfer the most seriously wounded. Maricosom responds by ordering the submarine to return to base instead, as the damage caused by the air attack prevents it from diving.

At 9:27 PM, the return telegram was sent. At 11.50 PM, during the return navigation (which had to be conducted by the second in command, as Scandola was injured), some planes launched four flares aft of Dessiè, 2 km away.

August 14th, 1942

At 2:22 AM, Dessiè sent the landing telegram. After passing through the obstructions at eight o’clock in the morning, the submarine moored half an hour later.

November 2nd, 1942

Dessiè sailed from Messina at 9.15 PM bound for Tobruk, for a mission to transport 20 tons of ammunition. The second battle of El Alamein, which would seal the fate of the Axis in North Africa, was raging.

November 5th or 6th,1942

The boat arrived in Tobruk at eight in the morning, disembarked the cargo and left at 16.10 to return to Messina. Following the defeat of the Italian-German armored army, Tobruk fell to the British on November 13th.

November 11th, 1942

The boat arrived in Messina at 8.15 am.

The Sinking

On the morning of November 18th, 1942, Dessiè, under the command of Lieutenant Alberto Gorini, set sail from Messina for a new mission off Bona (now Annaba), Algeria. On November 8th, Operation “Torch” had begun, the Anglo-American landing in French North Africa, and from that day on, droves of Allied merchant ships continued to pour men and equipment onto the coasts of Morocco and Algeria, signing the death warrant for the Axis troops in North Africa, who would soon find themselves caught between two fires in Tunisia: the British advancing from the east and the Americans from the west.

Many Axis submarines were sent to counter the influx of Allied men and materials into Algeria. Many were successful, but almost as many did not return.

Dessiè’s task was an ambush in front of Bona and night offensive bets in the harbor of Bougie and Philippeville. The submarine’s last communication with the base occurred at 7:12 PM on November 27th, 1942, when it regularly responded to a call, after that, Dessiè was never heard from again. Losing all hope, the crew was declared missing on December 23rd, 1942.

The incident became known after the end of the war.

Initially, it was believed that Dessiè had been sunk by depth charges from a Lockheed Hudson bomber of the Royal Air Force’s 500th Squadron, but further research found a version that better matched what was known about the submarine’s disappearance.

At 2:05 PM on November 28th, 1942, Dessiè was spotted proceeding on the surface towards the port of Bona by a British aircraft, which recalled two destroyers, the Australian H.M.A.S. Quiberon and the H.M.S. British Quentin.

In that period, Commonwealth Marine destroyers had undergone a modification to their depth charges, whereas previously they could be adjusted to explode at a maximum depth of 106 meters, they could now be adjusted to a maximum depth of 152 meters by applying a weight, which would have sunk them more quickly. This was because some submarines, subjected to bombardment with depth charges, had managed to elude the hunt by descending to a depth of 150 meters, a depth that until then the British considered impossible to reach and maintain. In addition, the sonars of British ships, due to the “direction” assumed by the sound waves, could not detect the presence of a submarine submerged at 150 meters, if it was 600 meters or more as the crow flies from their position.

H.M.S. Quentin (Lieutenant Captain Allan Herbert Percy Noble), being the destroyer assigned to “primary emergencies”, was the first to be sent to the scene, seven miles northeast of Bona. The boat carried out numerous attacks with depth charges, until it exhausted the entire supply (70 bombs), but without obtaining the slightest sign of damage inflicted on the submarine: no wreckage, not even a drop of fuel. Meanwhile, H.M.A.S. Quiberon (frigate captain Hugh Waters Shelley Browning), as a unit for “secondary emergencies” (in service for a few months, had never participated in a real anti-submarine hunt), was waiting in case its help was needed. The crew had a quiet lunch, then the men off duty went to rest. It was at that point that H.M.S. Quentin, having finished its depth charges, sent orders to H.M.A.S. Quiberon to go and hunt down the enemy submarine.

Leaving the port of Bona, H.M.A.S. Quiberon headed out to sea at high speed, while the crew was sent to the combat posts provided for antisubmarine actions. Speed was then reduced to 15 knots, to check the condition of the sonar.

Arriving in the area, H.M.A.S. Quiberon initially did not detect any echo that could reveal a submarine submerged in a radius of almost two kilometers. Dessiè was evidently crouched in a silent position, also taking advantage of the great disturbance caused in the mass of water by the depth charges of the Quentin and by its long crossing in the area at 12 knots, w\which confused the echoes that reached the sonar of the Quiberon, disturbing its search.

While H.M.S. Quentin searched the outermost area to make sure there were no other submarines in the area, H.M.A.S. Quiberon meticulously “sifted” the waters where the submarine was supposed to be, carefully examining any “disturbance” in the body of water. Expert Asdic operator Kendall reported each detection and comment to Lieutenant Physician John Hardcastle, who reported them. At one point, Kendall and anti-submarine armament officer Max Darling noticed a close-range bearing slightly different from the others. When Quiberon examined it with ASDIC, there was no echo. Another sound pulse was sent, and again there was no echo: the men of H.M.A.S. Quiberon were reminded of the Admiralty’s note, from a short time before, about submarines avoiding sonar by diving to a depth of 150 meters. It occurred to them that the submarine might be submerged at a deeper depth than the explosions of Quentin’s depth charges.

H.M.A.S. Quiberon

H.M.A.S. Quiberon moved away 1,370 meters, then approached the suspicious point by scanning the bearing that connected it to that position with sonar. This time there was an echo, faint and vague (the disturbances caused by the depth charges and the Quentin’s wakes were still felt, so much so that they hindered the maintenance of contact); It disappeared altogether when the distance became 550 meters. At this point, it was decided to carry out a test launch on H.M.A.S. Quiberon: five depth charges, three from the aft bomb launchers and two from the side bomb launchers. The destroyer then moved away again by 1,370 meters, moving into the least “disturbed” water it could find, returned to approach along the survey and regained contact (very faint, the echo could barely be heard at 1,000 meters away). It was so weak that, if the search speed of 7 knots had been increased to the minimum speed prescribed for the attack, 12 knots, the noise of H.M.A.S. Quiberon’s propellers would have been sufficient to make it lose. At a distance of 610 meters, the echo faded to the point of disappearing (there were still two minutes and 49 seconds left to reach the vertical of contact), but the Australian ship continued on its course. When it reached the vertical of the submarine, H.M.A.S. Quiberon launched five depth charges in the space of ten seconds, all adjusted to explode at the maximum depth, 152 meters.

H.M.S. Quentin

The crew of the destroyer waited, holding their breath, for the 70 seconds it took for the bombs to descend to a depth of 150 meters before exploding. It was impossible to imagine what the men of Dessiè were feeling at that very moment.

The silence was broken by the explosions of the five bombs, in quick succession. The Asdic operator of H.M.A.S. Quiberon, through the hydrophones, distinctly heard a noise as of hammering on metal, perhaps against a watertight bulkhead, then a slight whistle, followed by sounds indicating the breaking and crushing of something, which Kendall likened to eggshells being crushed in a paper bag. Finally, a dull thud, and then nothing, only silence. It was about three o’clock in the afternoon.

What was reported was the description given by Max Darling, Asdic operator of H.M.A.S. Quiberon, in the volume “Lost military ships” of the Historical Office of the Navy, as well as in the book “The Italian war on the sea” by Giorgio Giorgerini, the last moments of Dessiè were instead described differently. The submarine came to the surface, heeled and soared, evidently without control, and then immediately sank again from the stern, erectly. It would then have been located on the seabed, in position 37°04′ N and 07°49′ E (TN or 37°05’N, 07°55’E). The source of this version was unclear, as it was incompatible with the one described by Darling.

Soon after, H.M.S. Quentin appeared in front of H.M.A.S. Quiberon, advancing at 12 knots with the attack flag in the wind, and launched her last depth charge (there was only one left), then moved away again towards the open sea. H.M.A.S. Quiberon, about 730 meters away from the launch site, returned to the scene and saw, three minutes after the explosion of the bombs, a whitish turbulence perturbing the surface of the sea – for an area of two abundant acres – for a couple of minutes, then gradually extinguishing itself within another three minutes. The chief engineer of H.M.A.S. Quiberon believed that it was the gases produced by the explosion of the bombs, and the air contained in the submarine, which had now escaped from the torn hull. Entering the disturbed area in search of evidence of the submarine’s sinking, the destroyer found only air bubbles that continued to surface on the surface, and oil floating on the waves. Samples were collected, which were then analyzed and identified as belonging to four different types of motor oil. The chief engineer commented that they would hardly find more, considering that the submarine had imploded at a depth of 150 meters.

H.M.A.S. and H.M.S. Quentin, having finished their work, arranged themselves in a line and returned to Bona, continuing to scan the sea with their sonar.

Thus ended the life of Dessiè and the entire crew, 5 officers and 43 non-commissioned officers and sailors. They rest, in their “iron coffin,” in position 37°05’N, 07°55’E, 10 (TN, 16) miles north of Bona.

Original Italian text by Lorenzo Colombo adapted and translated by Cristiano D’Adamo

Operational Records

| Type | Patrols (Med.) | Patrols (Other) | NM Surface | NM Sub. | Days at Sea | NM/Day | Average Speed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Submarine – Coastal | 26 | 15193 | 4263 | 173 | 112.46 | 4.69 |

Actions

| Date | Time | Captain | Area | Coordinates | Convoy | Weapon | Result | Ship | Type | Tonns | Flag |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11/28/1940 | 03.05 | T.V. Adriano Pini | Mediterranean | 36°30’N-12°59’E | Torpedo | Failed | Glasgow | Light Cruiser | Great Britain | ||

| 8/12/1942 | 19.38 | T.V. Renato Scandola | Mediterranean | 37°38’N-10°25’E | WS21S | Torpedo | Sank | Deucalion | Motor Freighter | 7516 | Great Britain |

Crew Members Lost

| Last Name | First Name | Rank | Italian Rank | Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adella | Filippo | Junior Chief | Sottocapo | 11/28/1942 |

| Alianelli | Bernardino | Junior Chief | Sottocapo | 11/28/1942 |

| Aluffi | Francesco | Chief 2nd Class | Capo di 2a Classe | 11/28/1942 |

| Baldi | Giordano | Naval Rating | Comune | 11/28/1942 |

| Bampa | Attilio | Naval Rating | Comune | 11/28/1942 |

| Baroni | Mario | Naval Rating | Comune | 11/28/1942 |

| Bartoletti | Ugo | Junior Chief | Sottocapo | 11/28/1942 |

| Berlato | Giacomo | Junior Chief | Sottocapo | 11/28/1942 |

| Bilardello | Giuseppe | Chief 2nd Class | Capo di 2a Classe | 11/28/1942 |

| Brusadin | Teseo | Junior Chief | Sottocapo | 11/28/1942 |

| Caktieri | Giovanni | Junior Chief | Sottocapo | 11/28/1942 |

| Cardone | Vincenzo | Junior Chief | Sottocapo | 11/28/1942 |

| Carletti | Luigi | Chief 2nd Class | Capo di 2a Classe | 11/28/1942 |

| Cingati | Giuseppe | Naval Rating | Comune | 11/28/1942 |

| Colombo | Luigi | Naval Rating | Comune | 11/28/1942 |

| Coratella | Corrado | Junior Chief | Sottocapo | 11/28/1942 |

| Cremonesi | Carlo | Naval Rating | Comune | 11/28/1942 |

| Crispino | Domenico | Naval Rating | Comune | 11/28/1942 |

| D’angelo | Mario | Naval Rating | Comune | 11/28/1942 |

| Delle Noci | Giuseppe | Chief 2nd Class | Capo di 2a Classe | 11/28/1942 |

| Di Scala | Gaspare | Naval Rating | Comune | 11/28/1942 |

| Esposito | Michele | Junior Chief | Sottocapo | 11/28/1942 |

| Fontana | Antonio | Naval Rating | Comune | 11/28/1942 |

| Foresio | Domenico | Chief 3rd Class | Capo di 3a Classe | 11/28/1942 |

| Gambuzza | Vincenzo | Naval Rating | Comune | 11/28/1942 |

| Gianelli | Guido | Ensign | Guardiamarina | 11/28/1942 |

| Gorini | Alberto | Lieutenant | Tenente di Vascello | 11/28/1942 |

| Guidi | Alfredo | Naval Rating | Comune | 11/28/1942 |

| La Monica | Rosario | Chief 2nd Class | Capo di 2a Classe | 11/28/1942 |

| Lugani | Cesare | Naval Rating | Comune | 11/28/1942 |

| Lugniani | Guglielmo | Chief 2nd Class | Capo di 2a Classe | 11/28/1942 |

| Maranna | Felice | Sublieutenant G.N. | Tenente G.N. | 11/28/1942 |

| Marciano | Alfredo | Junior Chief | Sottocapo | 11/28/1942 |

| Miele | Ferdinando | Sergeant | Sergente | 11/28/1942 |

| Minniti | Giuseppe | Junior Chief | Sottocapo | 11/28/1942 |

| Mura | Silvio | Sublieutenant | Sottotenente di Vascello | 11/28/1942 |

| Mussi | Rino | Junior Chief | Sottocapo | 11/28/1942 |

| Orsini | Nello | Junior Chief | Sottocapo | 11/28/1942 |

| Pace | Catello | Chief 2nd Class | Capo di 2a Classe | 11/28/1942 |

| Pascali | Raffaele | Junior Chief | Sottocapo | 11/28/1942 |

| Piccinini | Giuseppe | Ensign | Guardiamarina | 11/28/1942 |

| Pinocchio | Arnaldo | Naval Rating | Comune | 11/28/1942 |

| Pipito | Giovanni | Naval Rating | Comune | 11/28/1942 |

| Rocchi | Ivan | Junior Chief | Sottocapo | 11/28/1942 |

| Rossi | Licinio | Junior Chief | Sottocapo | 11/28/1942 |

| Santambrogio | Angelo | Chief 2nd Class | Capo di 2a Classe | 11/28/1942 |

| Savioli | Bruno | Junior Chief | Sottocapo | 11/28/1942 |

| Vianello | Mario | Naval Rating | Comune | 11/28/1942 |