The Avorio was a coastal submarine of the Platino class small (TN 600 series, type Bernardis), 712 tons displacement on the surface and 865 tons submerged. The boat completed 15 war missions (7 patrols and 8 relocations), covering a total of 5,676 nautical miles on the surface and 685 submerged.

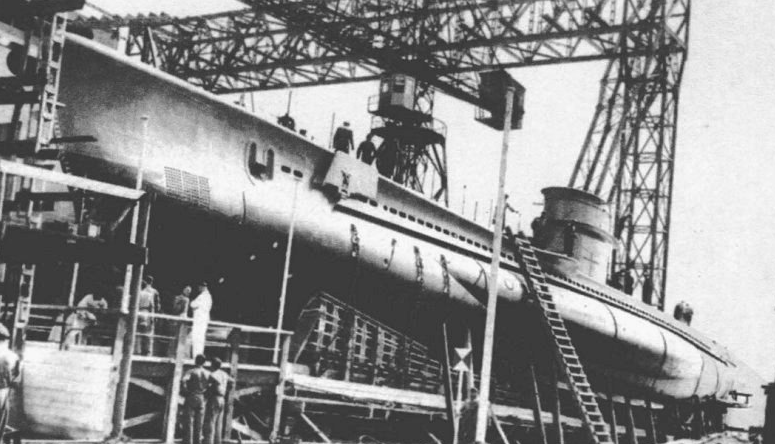

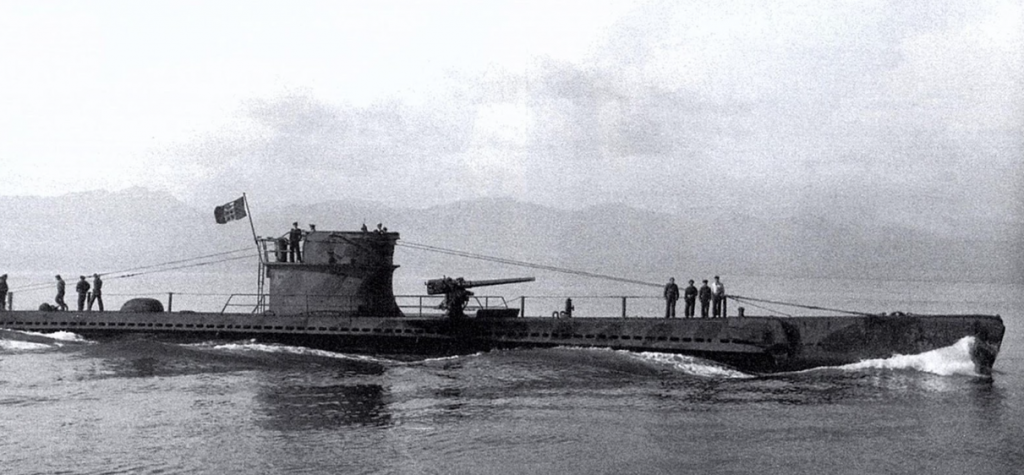

Avorio at sea

(U.S.M.M.)

Brief and partial chronology

November 9th, 1940

The Avorio was laid out at the Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico in Monfalcone (construction number 1266).

September 6th, 1941

The boat was launched at the Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico in Monfalcone. From November 1941, the fitting out was overseen by Lieutenant Marco Revedin.

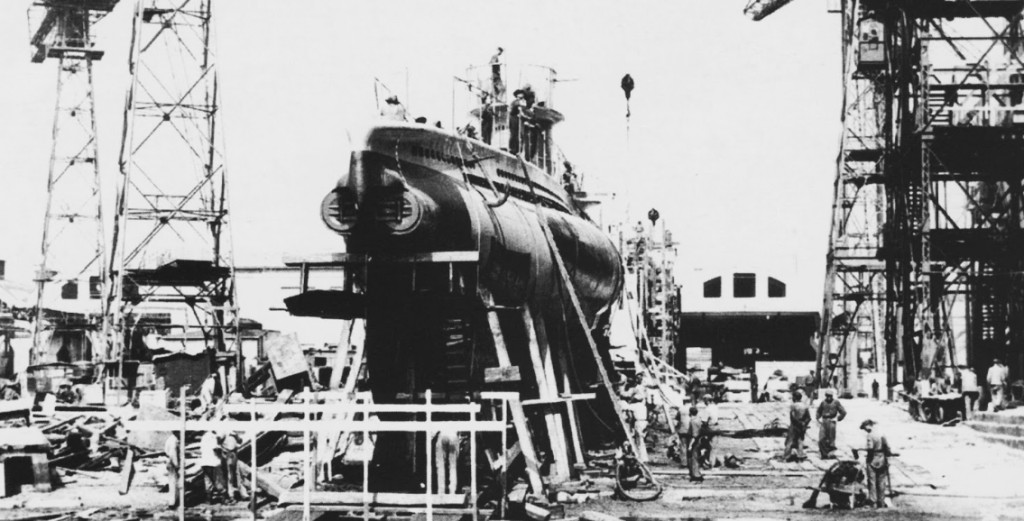

The Avorio still on the slip

From “Gli squali dell’Adriatico” di Alessandro Turrini

March 25th, 1942

The Avorio entered active service.

March-August 1942

Period of intensive training so that the boat could become operational as soon as possible.

At the beginning of August, after completing training, the unit was deployed to Cagliari and assigned to the VII Submarine Group.

May 20th,1942

Lieutenant Mario Priggione (28 years old, from Genoa) took command of the Avorio.

August 11th, 1942

The Avorio (Lieutenant Mario Priggione) departed Cagliari for its first war patrol during the air-naval battle of Mid-August. Along with nine other submarines (Alagi, Ascianghi, Axum, Bronzo, Cobalto, Otaria, Dandolo, Dessiè and Emo), it was deployed north of the Tunisian coast ( the assigned sector was located 20 miles from the coast of Tunisia), between Scoglio Fratelli (TN Sicily) and Skerki Banks (east of La Galite to the approaches of the Strait of Sicily, forming a barrier line of the western entrance to the Strait of Sicily, north of the La Galite- Skerki Banks junction), to attack the British convoy bound for Malta as part of Operation “Pedestal” (consisting of 14 merchant ships with the direct escort of 4 light cruisers and 11 destroyers, plus a support force composed of 2 battleships, 3 aircraft carriers, 3 light cruisers and 15 destroyers). The orders were to act with great offensive determination, launching as many torpedoes as possible against any target, merchant or military, larger than a destroyer.

Avorio, along with Dandolo, Cobalto, Granite, Emo and Otaria, formed a group operating west of La Galite.

August 12th, 1942

The Avorio arrived in the assigned sector, about fifteen miles north of Bizerte. During the day the crew heard bomb explosions but did spot anything. Based on the news received by radio regarding the movements of the convoy, it moved into the area and at 5.08 PM an enemy formation was finally spotted with the periscope proceeding on a course 90° (with Alfa 300°). It included numerous merchant ships and destroyers and there were three battleships behind which, from what look like masts in a lattice. Commander Priggione mistakenly believed they are Americans.

The periscope sighting was followed by detection from the hydrophones, which indicated a source covering a sector of about 40°. At the time of the sighting, merchant ships were about 8 miles away (with beta 80° on the starboard side), destroyers 6.5 miles away (with beta 70°-80° on the starboard side), and battleships less than 10 miles away (with beta 50° on the starboard side); wind and sea were completely calm, although there was a strong vibration.

The Avorio took a true course of 30° to attack the battleships, but at 5.16 PM two of the destroyers escorting the merchant ships (which preceded the battleships), approached on a beta 0°, leading commander Priggione (who excluded having been sighted, being still too far away) to believe that the whole convoy was approaching. The submarine continued its attack, checking with the periscope from time to time, and at 5:25 PM the two destroyers (one was H.M.S. Lookout, which having sighted the periscope of the Avorio, attacked it and then rejoined the convoy at 5:40 PM; the other was perhaps H.M.S. Tartar) were 3,000 meters away, again with beta 0°, while the convoy remained on the previous course (90°).

At this point Priggione concluded that he had certainly been sighted, therefore he ordered a slow dive to the depth of 40 meters, without disengaging. At 5.30 PM, the first four depth charges exploded nearby, and a systematic hunt began. The sources detected by the hydrophones remained in the aft sectors, with the boat stopping from time to time to listen. The Avorio then descended deeper, up to 100 meters, while the enemy ships continued to hunt it. In all, 180 depth charges were launched, while the ping of the sonar was distinctively heard.

Following various bearings to the south, looking for shallow waters, the Avorio finally manages to disengage after hours of chasing. At 10:25 PM, the hydrophones continued to report sound in the area, but Commander Priggione orders the boat to the surface to scan the horizon with binoculars. The observation reveals that there were no more enemy ships nearby. In conditions of absolute calm wind and sea, the Avorio headed north, starting to recharge the batteries and change the air.

August 13th, 1942

The Avorio moved several times according to orders given by the Submarine Squadron Command (Maricosom), looking for a burned aircraft carrier. At 4:21 PM, a cloud of black smoke was sighted. Believing it to be the reported aircraft carrier, the submarine reported to Maricosom. During the day, the Avorio sighted, and was sighted by, numerous aircraft.

At 7:38 PM, the boat was attacked by an aircraft and subjected to a short chase, with bombs being dropped.

August 13th through 15th, 1942

The nights of August 13, 14th, and 15th the Avorio continued to make various movements according to the orders it had received from Maricosom.

August 14th, 1942

At 5.16 PM the Avorio, and the other submarines of his group (in the meantime reduced by three units, following the sinking of the Cobalto, the damaging of the Dandolo and the return of the Granito, which had spent all its torpedoes), were ordered to emerge and move immediately to sub quadrant 5 of quadrant 0434, where the presence of an immobilized and damaged enemy cruiser had been reported, to sink it. Subsequently, since this information turned out to be erroneous, another message was sent ordering the submarines, once they arrived at the point indicated in the previous order, to assume began patrolling in the same manner as before, in an area located 140 miles west of the one in which they were previously located.

In the evening, the Avorio and the other boats of the group were ordered to move 30 miles further west, to attack any British units sailing back after the surviving merchant ships of “Pedestal” had arrived in Malta.

August 16th, 1942

In the afternoon, the Avorio attempted an attack on the surface based on a hydrophone pickup, but did not spot any ships.

August 17th, 1942

The submarine was back in Cagliari.

August 18th, 1942

At 00.27 the Avorio (Lieutenant Mario Priggione) left the moorings and headed out of the port of Cagliari.

The Battle of Mid-August had just ended, but at 6.50 AM on the 17th, a group of British ships (the aircraft carrier Furious, a cruiser and seven destroyers) was sighted off Algiers, and it was also reported that on 16th other British ships were preparing to leave Gibraltar. This information determined a state of alarm and the order to put to sea all submarines in readiness, Avorio included.

At 00.37 AM, once the port obstructions were cleared, the Avorio headed towards the conventional point “Z”, and at 2.55 AM, when it was close to this point (in the waters between Sardinia and Tunisia), and on the surface recharging the batteries (proceeding at 8 knots on a true 164° course), it sighted only 500 meters away, on alfa 90°, an unknown submarine with beta 30° to starboard and 50° course. It was the British P 211 (later Safari, Commander Benjamin Bryant).

The Avorio at sea

(From the magazine Storia Militare)

The enemy submarine was approaching and aiming at the Avorio, which in turn approached full rudder to port and – since torpedoes 5 and 6, the aft ones, were ready to launch and the order of operations prohibits attacking other submarines – it turned its stern to P 211. Despite the order not to attack other submarines, motivated by the fear of possible incidents of “friendly fire” due to the many Italian boats at sea in the Central Mediterranean, Commander Priggione correctly judges that the newcomer could not be an Italian submarine, both because he has not been informed of the arrival of a Italian submarine bound for Cagliari, and because Priggione knew that Italian submarines, as a rule, made landings at other points. As soon as the Avorio had its stern to the enemy, however, he dove, disappearing before an attack was possible.

At 3.30 AM the Avorio returned to take a 164° course, and at 3.18 AM it launched the signal of discovery, to warn of the presence of the enemy unit in the area. Then, it continued the navigation to the assigned sector.

At six o’clock in the morning, the Avorio sighted about 5.5 miles away the steamship Perseo (Captain Giorgio Blok), bound for Cagliari following a rerouting order issued by Supermarina – due to an erroneous sighting of enemy warships by the destroyer Maestrale – while it was sailing from Bagnoli (Naples) to Bona (Tunisia). At first, Commander Priggione, given that the Perseo had a funnel at the stern (unusual at the time for cargo ships, but common for tankers), believed he has encountering a large oil tanker, which presented itself at the crossbeam (the two units were sailing on the opposite direction). Priggione had been informed of the transit of the Perseus rerouted from Tunisia to Cagliari, and, although confused by the appearance of the ship (which “from the estimate must have been a steamer”, while from the appearance it looks like a tanker), on the basis of the course he was following (350°) assumed that the ship encountered was indeed the Perseus (which, however, he still assumed to be an oil tanker), so he turned around to recognize it. At the same time, given that in the three hours that had elapsed since the launch of the detection signal no message has been received or intercepted that referred to the presence on the landing point of the submarine sighted at 2.55 AM, Priggione correctly assumes that the Perseus had not been informed, so he tried to get as close as possible to warn the ship of the danger.

However, this is how a misunderstanding with fatal consequences began. Having spotted the Avorio, the Perseus mistakenly believed that it was an enemy submarine, and it soon as it spotted it approaching towards it, accelerated to move away. Commander Prigione tried to call the Perseus with a flashing light, receiving no answer. He then tried to catch their attention with the searchlight, but again to no avail. The Avorio accelerated to its maximum speed and reduced the distance to 4500 meters, but in the meantime, under the light of dawn, it was noticed that the stern gun of the steamer was pointed at the submarine. Moreover, the Perseus had in turn increased speed further, as the distance between the two units remained constant. From 6.05 to 6.40 AM the Avorio continued unabated and by any means possible to call the Perseus but, despite the fact that at that distance the signals made with the searchlight should be perfectly visible, no response came from the merchant ship, which instead continued its escape.

In reality, on the Perseo it was noted that the unknown submarine made “some brief optical signals”, but it was only possible to understand the segment “ENEMY ?”; an attempt was made to answer with a flashing light, but these signals were not seen by the Avorio, as it was already too bright. The Perseus then tried to respond with the masthead light, but as soon as the switch was activated, a fuse burned, making the light unusable. The ever-increasing distance between the steamer and the submarine had become too great to allow effective communication.

At 6.40 AM, the Avorio transmitted the message “Sighted enemy submarine in lat. 38°51’40” – and lon. 9°29’40”. Be careful”, but this time the Perseus did not answer either; at 6.47 AM, finally, Priggione gives up any further attempt, and the Avorio returned to its original course.

The Perseus, which could not be informed of the danger, ended up right in the jaws of P 211: at 9.25 AM it is torpedoed by the British submarine, and then sank at 11.50 AM.

The Avorio, meanwhile, continued its course, navigating on the surface. At 10.31 AM, having arrived in the assigned area, it dove, then waited in ambush at periscope depth.

At 7:36 PM, the submarine resurfaced and, on Maricosom’s orders, began to sail back.

Having clarified the situation, in fact ( the Furious group was at sea to launch planes bound for Malta to replenish its air forces – it had become known that in Gibraltar, before leaving, the aircraft carrier had embarked 35 Hawker Hurricane fighters – while the ships departing from Gibraltar on the 16th were headed to the Atlantic and England, not to the Mediterranean), The alarm has concluded, and all submarines were recalled to port.

August 19th, 1942

According to a new order, the Avorio reaches Trapani instead of Cagliari.

November 5th through 7th,1942

The Avorio (Lieutenant Mario Priggione) was sent to the waters off Algeria along with numerous other Italian submarines (twenty: Axum, Argo, Argento, Asteria, Acciaio, Aradam, Alagi, Bronzo, Brin, Corallo, Dandolo, Diaspro, Emo, Mocenigo, Nichelio, Platino, Porfido, Topazio, Turchese and Velella), to counter the “Operation Torch”, the Anglo-American landing in French North Africa. Avorio, in specifically, was located north of Bizerte along with the Bronzo, Alagi, Corallo, Diaspro and Turchese.

The landings began on November 8th: 500 Anglo-American transport ships, escorted by 350 warships of all kinds, disembarked a total of 107,000 soldiers on the coasts of Algeria and Morocco.

November 6th, 1942

The Avorio was sighted at one o’clock in the afternoon by the British submarine P 46 (later Unruffled, Lieutenant John Samuel Stevens), which, however, given the excessive distance, did not even attempt to attack it,

November 9th, 1942

At 7:09 PM the command of the Italian submarine fleet, Maricosom, reported to all the boats at sea that enemy steamers were moving eastwards, and that landings were taking place in Bona and Philippeville. Therefore, it gave the order to attack any merchant or military ship leaving those ports but avoid (in order not to risk incidents of “friendly fire” with other units sent to the area) attacking submarines, MAS and motor torpedo boats.

November 11th, 1942

At 5:56 PM Maricosom informed the submarines that enemy troops were landing in the waterfront of Bougie, and ordered the Avorio and other submarines (Argento, Ascianghi, Argo, Diaspro , Emo) to move immediately to this area to attack “without any limitation with energy and determination”, and then return the following day to the assigned ambush sectors.

The Avorio then headed full speed towards Bougie but was spotted by enemy ships and subjected to a systematic anti-submarine chase from dawn to dusk on the 11th, without however suffering any damage.

November 24th, 1942

During the morning, the Avorio, sailing towards Bougie (Algeria) for an offensive reconnaissance, sighted off Cape Carbon a darkened ship proceeding at low speed. Due to continuous rainfall, it was difficult to recognize the ship, which turned out to be a thin enemy unit, probably a destroyer. The Avorio reduces the distance to less than 800 meters, then attacked the ship by launching a salvo of three torpedoes, after which it disengaged by diving deep to escape any reaction. After 40 seconds (the time allowed for the torpedoes to reach their target) some detonations were heard, leading to the belief that the enemy ship was sunk, but in reality, the torpedoes missed the target.

The Avorio then penetrates the bay of Bougie and carried out the planned reconnaissance but did find enemy ships.

January 9th, 1943

At 11:47 PM, the Avorio, while sailing towards its patrol area located off the coast of Tunisia, was suddenly attacked by an aircraft. The submarine immediately began the rapid dive maneuver, but the late closure of the diesel engines’ intakes caused an abundant amount of water to enter the boat, forcing it to return to the surface; the Avorio opend fire with its machine guns on the attacking aircraft, damaging it. Hit several times, the aircraft retreatd, leaving a trail of smoke in its wake.

Due to the damage caused by the water taken aboard in the rapid immersion maneuver, however, the Avorio had to return to port.

January 24th, 1943

At 1:16 AM, the Avorio, navigating towards the bay of Bougie, sighted an enemy ship off Cape Carbon and attacked it with torpedoes, but failed to score a hit. (According to one source, the Avorio sunk the armed trawler Stronsay, but in fact this ship was sunk on 5th February, several days later, and by a collision with a mine).

February 3rd,1943

Lieutenant Priggione handed over command of the Avorio to Leone Fiorentini (27 years old, from Livorno).

February 5th, 1943

According to some sources, the Avorio torpedoed and sank the British armed trawler Stronsay, weighing 545 tons, off the coast of Philippeville. In reality, as shown by archival research by historian Francesco Mattesini, the Stronsay almost certainly sank due to collision with mines laid by German motor torpedo boats of the 3. S-Boote Flotille, and in any case twenty-four hours before the Avorio (which never fired torpedoes during its last mission) had arrived in the area.

The Sinking

On February 6th, 1943, the Avorio, under the command of Lieutenant Leone Fiorentini, sailed from Cagliari for a new mission in Algerian waters. The boat had been assigned an operational sector along the coast between Bona and Philippeville, where it was to operate in liaison with other submarine units.

On the evening of February 8th, the submarine, after having remained submerged during the day, emerged in the dark to recharge its batteries, proceeding to the surface at 7 knots with all the hatches open, performing hydrophone listening to detect any approaching units (but the noise of the engines disturbed the use of the hydrophone, greatly reducing its effectiveness). At midnight the Avorio, while sailing on the surface east of Algiers, intended on recharging the batteries, sighted at a short distance the Canadian corvette H.M.C.S. Regina (under the command of the Lieutenant Commander – or more precisely, “acting lieutenant commander”, Harry Freeland), apparently alone, engaged in a antisubmarine patrol.

H.M.C.S. Regina was escorting the steamer Brikburn, sailing from Algiers to Bona with 1,500 tons of gasoline in barrels; along with a second merchant ship, the Brikburn had lagged behind the rest of the KMS 8 convoy (which had departed Londonderry on January 21st, with 53 merchant ships, escorted by 9 Canadian corvettes and 6 British units). It was now a small group of two stragglers escorted by H.M.C.S. Regina and the British minesweeper H.M.S. Rhyl. The Avorio, however, only sighted H.M.C.S. Regina without noticing the presence of the other ships. Judging the position of his boat unsuitable for an immediate attack, which moreover would have involved more risks than benefits (a corvette was a rather modest target in terms of tonnage, while teasing it could have triggered a deadly reaction, being a ship specifically designed for anti-submarine warfare), Commander Fiorentini gave the order to dive deep, in order to avoid a possible chase by the enemy ship. H.M.C.S. Regina, being 3,660 meters forward to the left of the small convoy, had already located the Avorio with her radar at 11.10 PM, while this was still on the surface. (According to Canadian sources, the Avorio would spot H.M.C.S. Regina at the last moment, while she was already attacking, and did a rapid dive while changing his course.)

It was the radar operator Joseph Saulnier who had made the first generic radar contact three and a half miles away. He had gone to the officer of the watch to report it, but the latter, despite resorting to night vision instruments, had been unable to see anything. Saulnier, confident that he had seen something on the radar, then woke up Commander Freeland, who had ordered him to turn back.

H.M.C.S. Regina approached the contact to find out what it was, increasing speed to 12 knots, and the radar contact was soon lost, as the Avorio had dived. At the same time, however, the corvette gained asdic (sonar) contact at 915 meters and went on the attack.

The first discharge of ten depth charges caught the Avorio while it was at a depth of about 60 meters (according to another source, however, the ten bombs launched by H.M.C.S. Regina were adjusted to explode at depth between 15 and 42 meters), immediately causing very serious damage: the rudder was put out of action, the torpedo tubes were deformed, and the hull had cracked; It became impossible to maintain buoyancy while submerged, and there were several leaks

Commander Fiorentini had no choice but to order to emerge, giving full air to the tanks, and attempting to give battle on the surface, and, if possible, escape the corvette by pushing its engines to the maximum (since the maximum speed achievable on the surface was much greater than submerged). H.M.C.S. Regina, meanwhile, after launching the first volley of ten depth charges, had moved 915 meters away from the point of attack, and then reversed course to attack again on a course parallel and opposite to that of the previous attack.

When the Avorio surfaced (five minutes after the launch of the first depth charges), it was discovered that the damage caused by the depth charges had also disabled the cannon: between this and the deformation of the forward torpedo tubes, the only weapon that the submarine could still oppose to the enemy ship was a 13.2 mm Breda twin machine gun. As if that was not enough, the jamming of the rudder, caused by the bursts of the depth charges, prevented the boat from keeping on course, forcing it to describe a series of “S” turns.

Nevertheless, the Avorio still attempted to engage in combat and on the surface. With the only machine gun remaining effective, the submarine attempted to hit H.M.C.S. Regina’s bridge, which in the meantime zigzagged to disturb the boat’s fire and opened fire in turn. On H.M.C.S. Regina ‘s bridge, Second Lieutenant Doug Clarance, standing next to a machine gun, saw the trail of a tracer heading towards the submarine, and then seemed to come back: he then realized that the Avorio was returning fire, and “suddenly I found myself six feet taller than I wanted to be.”

Sailor Gib Todd, chief of the 40 mm “pom-pom” quad machine gun located on the aft deck of the corvette, landed a few hits on the submarine, whose lone machine gun for its part “splashed with abundantly water ” its quad, with a shot that was “unpleasantly close” but which caused no damage or injuries. It all happened so quickly that Todd didn’t even have time to be afraid; He was more afraid when things were done, when he thought about what could have happened.

The fire of the Avorio’s machine gun did not cause damage to the corvette, while H.M.C.S. Regina’s shot s were precise and devastating: from the outset, several gun shots and machine gun volleys had repeatedly hit the Italian boat, causing further and serious damage and decimating the crew. The firing of the 20 mm Oerlikon machine guns on the bridge, the first to fire, silenced the Avorio machine gun, while the deck gun and the pom-pom quad swept the deck of the submarine, killing or wounding all who were there.

A 101 mm projectile hit the conning tower at its base and killed commander Fiorentini, the second in command, second lieutenant Silvio Grandesso Silvestro, and the navigational officer, along with other men. In the brief but bloody battle, more than half of the Avorio’s crew was killed or wounded.

The survivors began the scuttling maneuvers and then began to abandon the unit. H.M.C.S. Regin, seeing that the submarine was now out of action, ceased fire and interrupted a ramming maneuver she had just begun, pulling over. The corvette had fired a total of eight rounds from the 101 mm gun, 20 rounds from the 40 mm “pom-pom” and 635 rounds with the 20 mm Oerlikon machine guns.

La news of the sinking of the Ivory on the front page of Toronto’s “Evening Telegram”. The tone of the article follows the line dictated by the directives of British propaganda, always contemptuous of Italians

Commander Freeland of H.M.C.S. Regin ordered the surviving Italians to keep the submarine afloat, “or worse for them”. The corvette inspected the surrounding area for a quarter of an hour to make sure there was no other submarine, then sent a boarding squad on a launch, with orders to check the severity of the damage and assess whether it was possible to tow it to port. Nine men took their places in the boat; sailors Vic Martin and Byron Nodding rowed to the submarine, after which the boat boarded the dying Avorio, which was sinking very slowly, with the intent of capturing it. The stern of the Avorio was already low on the water; survivors who had not already jumped into the water were standing on the bow.

Six men boarded the submarine and began to round up the survivors of the Italian crew, who were then transferred to H.M.C.S. Regin on several voyages. As the corvette kept moving in order not to become a fixed target in the event of an attack, it sometimes struggled to track the dingy in the darkness.

Among the six members of the boarding party was Sergeant Raymond Alexander, who noticed that the bow of the Avorio had been “opened” by depth charges. A couple of his comrades were armed with pistols, and they handed him a machine gun, saying that if there was any trouble, he would have to do nothing but pull the trigger. One of the six men on the boarding party spoke Italian, which greatly facilitated communication with the prisoners.

All the surviving Italians were transferred to the Regina with the exception of the chief engineer and a non-commissioned officer, who were kept on board to force them to try to restart the engines and bring the submarine to run aground on the coast. Raymond Alexander received a pistol and orders to take the Italian non-commissioned officer below deck and go to the engine room, to see if anything could be done. So, he did, but the two found themselves knee-deep in water; Unable to speak to the petty officer due to differences in language, Alexander motioned for him to come back, and they both went back on deck, while the Avorio continued to lower itself to the water. The Canadian also took out a pair of binoculars, which he kept for himself.

Survivors of the Avorio aboard H.M.C.S. Regina

(Jim Peters – from www.thememoryproject.com)

Another member of the boarding party, John W. Potter, was ordered to go down to the submarine and retrieve all the documents he could find. Once inside the narrow half-flooded room, alone, he was seized by claustrophobia, quickly grabbed what he found and then hurried back on deck, and then deposited in the H.M.C.S. Regina life boat what he had recovered on the Avorio.

The scuttling maneuver attempted by the crew had not been very effective, also because the damage caused by the depth charges had caused the flooding of the depot in which the explosive charges for self-destruction were placed. However, reconnaissance by the boarding team (which inspected all the rooms still accessible) showed that the submarine was unable to move by its own means. Commander Freeland of H.M.C.S. Regin decided not to attempt towing her ship, because the explosions of the depth charges had knocked out her radar, and he feared being attacked by another submarine while slowed by the heavy burden of towing the Avorio. Nevertheless, not wanting to give up appetible prey, Freeland requested a tugboat, and at 3:45 AM the military tugboat Jaunty arrived on the scene.

It was possible to secure the submarine to a tow cable, but the damage suffered by the Avorio was too severe: by five o’clock in the morning the water on board was too much to hope to keep it afloat, and the crew of the Jaunty cut the tow cable. Raymond Alexander later recalled that he and the other members of the boarding party asked the tugboat to take them on board, since the submarine was sinking, but from the Jaunty they replied that there was no talk of it, and then left. H.M.C.S. Regin then sent a boat to recover the six men of the squadron and the two Italians who had been detained on board with them.

On the Avorio the eight men, standing on the deck, found themselves with water up to their knees. Alexander told the others that he was going to jump, and he did, followed by the others. Once in the water (he still had the binoculars he had taken on board the boat around his neck, which he would take home with him), he looked around and saw the bow of the Avorio rise into the sky and then sink rapidly.

February 9th, 1943, at 5:15 AM, the Avorio sank in position 37°10′ N and 06°42′ E, off Philippeville and Cape Bougaroni.

H.M.C.S. Regina lifeboat fished out of the sea, one after the other, the six men of the boarding party and the two Italians. On the Queen, the survivors of the Avorio were astonished to find someone in the Canadian crew who spoke their language. They were cleaned and fed, and then disembarked in Bona, interrogated, and sent to captivity.

Eight of H.M.C.S. Regina’s crew were decorated for sinking the Avorio; Commander Freeland received the Distinguished Service Order, while radar operator Joseph Saulnier, who had gained first contact, was mentioned in the dispatches.

Of the 46 men who made up the crew of the Avorio, 27, including seven wounded (two of them seriously), were rescued by H.M.C.S. Regina and taken prisoner, while another 19 lost their lives: three officers (including Commander Fiorentini), three non-commissioned officers and 13 sub-chiefs and sailors.

Their names:

- Giovanni Campus, sub-chief radiotelegraphist, missing

- Dante Cappellini, sailor electrician, missing

- Domenico Cascella, sailor furiere, missing

- Francesco De Angelis, sailor and motorcyclist, missing

- Guido De Bortoli, radio telegraph sergeant, missing

- Antonio De Francisci, midshipman, missing

- Giocondo De Longhi, sailor, missing

- Carletto Fabro, sub-chief gunner, missing

- Leone Fiorentini, lieutenant (commander), missing

- Antonino Galati, sailor, missing

- Sergio Grandesso Silvestri, second lieutenant (second in command), missing

- Edmondo Peretti, gunnery sergeant, missing

- Paolo Pittalis, torpedo sailor, missing

- Adolfo Querzola, sub-chief radiotelegraphist, missing

- Luigi Romano, sailor and motorcyclist, missing

- Umberto Servillo, torpedo sailor, missing

- Gino Soave, sub-chief electrician, missing

- Mario Stucchi, sub-chief radiotelegraphist, deceased

- Benedetto Zappa, sailor helmsman, missing

A twentieth member of the crew, electrician sergeant Giuseppe Ferrara, died in captivity on 27 March 1945 at Melcombe Regis, UK. He is buried in the military cemetery of Brookwood, Surrey, along with three hundred other Italians of all branches who died in captivity on British soil.

Giuseppe Ferrara’s grave in Brookwood Cemetery (Surrey, England)

(from www.findagrave.com)

At least two of the Avorio men had not been able to participate in the last mission, for different reasons, and had thus been saved.

Sergeant electrician Enrico Casagrande, from Frascati, had to disembark on February 2nd, six days before departure, due to a wound sustained during the previous mission, which had become infected. He learned of the loss of the Avorio while he was hospitalized at the military hospital of La Maddalena. Sixty-two years later, Casagrande, who had become president of the ANMI (Navy veterans) group in Frascati, would succeed in having a monument built in Cagliari in memory of the men of the VII Submarine Group who disappeared at sea with their boats, which left the Sardinian base and never returned: in addition to the Avorio, Adua, Acciaio, Asteria, Alabastro, Aegento, Cobalto, Corallo, Dagabur, Emo, Gorgo, Malachite, Pordido, Tritone, Topazio, Veniero, e Zaffiro.

The monument to the men of the VII Grupsom who disappeared at sea during the war

(Photo ANMI)

A happy ending, in a certain sense, is the story of Giuseppe (Joseph) Costanzo, sailor and helmsman of the Avorio. Costanzo was the son of an Italian-Canadian father (an Italian who emigrated to Canada and became a railroad worker in Schreiber, Ontario) and an Italian mother; he had his father, uncle and several cousins in Canada, but he was born in Italy, and at the time of the entry into the war he was in Italy, which had become an enemy of Canada. In his family, siblings and cousins had found themselves fighting on opposite sides. Forced to remain in Italy, in December 1941 Costanzo, twenty years old, was conscripted by the Regia Marina and subsequently embarked on the Avorio; with his companions in the submarine’s crew he had forged indelible bonds of friendship, almost fraternal.

In early February 1943, while drinking in a bar in La Spezia, Costanzo was insulted by another sailor, who called him “Canadian shit” and insulted his father. Constantius, who had drunk a lot and could not tolerate his father being offended, responded with one punch, the other reacted in the same way, and soon knives were drawn as well. Their comrades intervened to stop them. Since the sailor he had punched was of higher rank, Constantius was arrested, demoted, and sentenced to two months’ imprisonment and a month’s suspension of pay. Eight days after his arrest, the Avorio had set sail without him on what was his last mission.

When he was released from prison, Constantius learned that the Avorio had not returned from its patrol. For a month, he went to the radio station in La Spezia every day to ask if there was any news, but each time the answer was the same: “Avorio doesn’t answer.” After some time, the submarine was declared lost at sea with all its crew. Due to a bureaucratic error, Constantius himself was declared missing at sea, and a small funeral ceremony was even celebrated in his country, before the misunderstanding was cleared up.

Costanzo was assigned to another submarine, the Sirena, on which he served until the armistice of September 8th, 1943. After sinking the boat, which was under construction, and fortunately escaping capture by German soldiers, Costanzo managed to cross the lines and reach his hometown, in southern Italy, where he returned to the ranks of the Navy and was again embarked on submarines, now used for the training of Allied anti-submarine vehicles. In 1947 he was finally able to reunite with his father and the rest of the family in Schreiber, Canada, where he settled, started a family, and lived for the rest of his life.

For sixty years, Costanzo believed that the Avorio had sunk with all the crew, including many of his great friends, whose memory drove him to tears even after so many years. Marchi, the musician who swore that he would marry the prostitute he loved; Battaglia, the officer whose sister Costanzo courted in Venice; Soles, the prankster with whom he spent his free time; the commander, whom he adored.

When in 1994 his son Robert, studying Canadian military history, discovered that the Avorio had been sunk by HMCS Regina, the thoughts that a Canadian ship had caused the death of his friends only aggravated the pain of Costanzo, who had now become a full-fledged Canadian. In 2003 Robert Costanzo discovered almost by chance from his lawyer, a naval history enthusiast, the complete story of the sinking of the Avorio. Joseph Costanzo was thus able to learn, at the age of 82, that his companions in the Avorio had not all died at sea; more than half, including some of his best friends, had actually survived.

In the years that followed, Costanzo, who had never wanted to talk about the war so as not to bring back the memory of his friends who he believed dead, managed to contact several veterans of H.M.C.S. Regina, former enemies who had now become compatriots, with whom he shared images and stories of that distant era, although he was unable to track down his old companions in the Avorio.

Original Italian text by Lorenzo Colombo adapted and translated by Cristiano D’Adamo

Operational Records

| Type | Patrols (Med.) | Patrols (Other) | NM Surface | NM Sub. | Days at Sea | NM/Day | Average Speed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Submarine – Coastal | 15 | 5676 | 685 | 45 | 141.36 | 5.89 |

Actions

| Date | Time | Captain | Area | Coordinates | Convoy | Weapon | Result | Ship | Type | Tonns | Flag |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2/5/1943 | – | T.V. Leone Fiorentini | Mediterranean | Philippiville | Torpedo | Failed | Uknown | Uknown | Unknown |

Crew Members Lost

| Last Name | First Name | Rank | Italian Rank | Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Campus | Giovanni | Sub-chief radiotelegraphist | Sottocapo radiotelegrafista | 2/9/1943 |

| Cappellini | Dante | Sailor electrician | Marinaio elettricista | 2/9/1943 |

| Cascella | Domenico | Sailor | Marinaio | 2/9/1943 |

| De Angelis | Francesco | Sailor | Marinaio | 2/9/1943 |

| De Bortoli | Guido | Sergeant radio telegraph | Sottocapo radiotelegrafista | 2/9/1943 |

| De Francisci | Antonio | Midshipman | Guardiamarina | 2/9/1943 |

| De Longhi | Giocondo | Sailor | Marinaio | 2/9/1943 |

| Fabro | Carletto | Sub-chief gunner | Sottocapo cannoniere | 2/9/1943 |

| Fiorentini | Leone | Lieutenant | Tenente di vascello | 2/9/1943 |

| Galati | Antonino | Sailor | Marinaio | 2/9/1943 |

| Grandesso | Sergio | Lieutenant | Tenente di vascello | 2/9/1943 |

| Peretti | Edmondo | Sailor torpedoman | Marinaio silurista | 2/9/1943 |

| Querzola | Adolfo | Sub-chief radiotelegraphist | Sottocapo radiotelegrafista | 2/9/1943 |

| Romano | Luigi | Sailor | Marinaio | 2/9/1943 |

| Servillo | Umberto | Sailor torpedoman | Marinaio silurista | 2/9/1943 |

| Soave | Gino | Sub-chief electrician | Sottocapo elettricista | 2/9/1943 |

| Stucchi | Mario | Sub-chief radiotelegraphist | Sottocapo radiotelegrafista | 2/9/1943 |

| Zappa | Benedetto | Sailor helmsman | Marinaio nocchiere | 2/9/1943 |