The Atropo was a Foca-class minelaying submarine (displacement 1305 tons on the surface, 1625 submerged). The boat differed from the twin vessels Foca and Zoea in the periscopes, which were both of the Galileo type, while on the twin boats they were one of the Galileo and one of the San Giorgio types. The Atropo and Zoea were powered by Tosi engines, the Foca by FIAT engines.

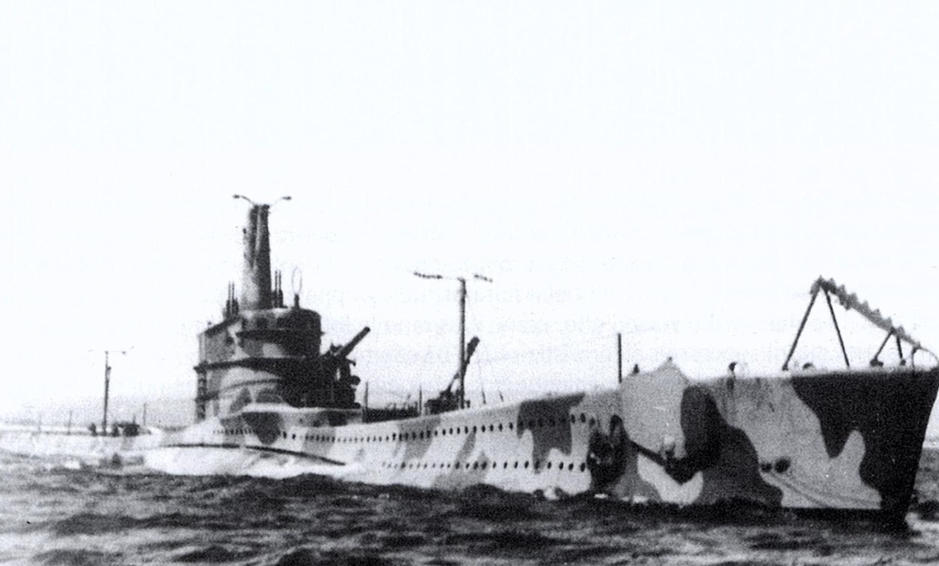

The Atropo in 1941, with a camouflage scheme with spots with rounded edges instead of straight edges

(From the Magazine Storia Militare)

During the 1940-1943 conflict the submarine completed 30 war missions, all in the Mediterranean, covering 27,884 miles on the surface and 2,703 submerged and spending 171 days at sea. It was the most active submarine in transport missions, carrying out 23 of them. After an accident in the first mine-laying mission, in fact, it was withdrawn from this use and assigned almost exclusively to transport tasks, for which it was particularly suitable precisely because it could transport a considerable number of supplies in the holds normally reserved for mines.

After the armistice, during the co-belligerence (September 1943-September 1945), the Atropo carried out three transport missions for the Dodecanese garrisons and participated in 118 exercises in the Atlantic with Allied anti-submarine vessels.

The boat’s motto was “Relentlessly.”

Brief and partial chronology

July 10th, 1937

Setting up started at the Franco Tosi shipyards in Taranto.

November 20th, 1938

Launch at sea at the Franco Tosi shipyard in Taranto.

February 14, 1939

Entry into service, third and final unit of the class.

The sub-chief engineer Santo Rettondini (born in San Pietro di Morubbio (TN Near Verona)) October 21st, 1920), who volunteered for the Navy in 1938 and was a crewmember of the Atropo for the duration of its operational life (1939-1946), would recall, in an interview held more than seventy years later, an incident that occurred during the tests of the Atropo:

“… There were still civilians who came and worked on the boat, modifying certain things, and doing other things. The company’s technicians (…) Not many days had gone by, one day they said, “Tomorrow we’re going out to sea, we’re going to do depth tests.” And the workers on board also come (…) Let’s go out to sea, and there I had my first baptism. It was a scare, which I will remember for the rest of my life. We were out at sea, we started to dive, and down, and down, and down… When we reached a depth of 80 meters, a gasket came off a door (TN probably a Kingston) in the control room, and sea water started pouring in: it looked like bullets. Fortunately, the chief boatswain, who was (…) at the helm, had the readiness to give air to the tanks to go up, and he let this air so intensively, that when we came out of the sea we jumped and fell on one side, like this. I stuck to my engine control wheel… The emotion I felt was tremendous, because it was the first time, I found myself in those conditions there… not knowing what had happened (…) Then we entered port, and the workmen continued to work on this defect, but they said they wouldn’t come out to rehearse anymore, because they had gotten a fright too. They said, “We’re not coming anymore.” That was my baptism [at sea] I had when I was embarked on the submarine Atropo.”

Together with the twin boats Foca and Zoea, the Atropo was assigned to the XLV Submarine Squadron (IV Submarine Group of Taranto), to which belonged all the other minelaying submarines of the Regia Marina: Pietro Micca, Marcantonio Bragadin, Filippo Corridoni, X 2, and X 3.

In peacetime, it carries out intensive training and mine-laying exercises with inactive ordnance.

April 1939

The Atropo took part in operations related to the occupation of Albania. During this period, Ensign Licio Visintini, future Gold Medal for Military Valor, served on the Atropo.

June 1939

During the celebrations for the Naval Week of the year XVII (NT Fascist Calendar, from October 29th, 1938 to October 28th, 1939), the Atropo received its combat flag in Livorno, along with eleven of the twelve new Soldati-class destroyers. The ceremony was attended by representatives of the armed forces and the secretary of the PNF (NT Fascist Party) Achille Starace; the combat flags of the new units were blessed by the military ordinariate, Monsignor Bartolomasi.

June-July 1939

The Atropo made a cruise from La Spezia to El Ferrol (Atlantic coast of Spain), under the command of Commander Luigi Gasparini (one of the most experienced and prepared submariners of the Regia Marina), to test the conditions for crossing the Strait of Gibraltar, in view of a possible future use of Italian submarines Atlantic. It was necessary to collect information on the possibilities of going out into the Atlantic and especially of crossing the strait, the passage of which is rather complex from a nautical and hydrographic point of view.

Navigation took place submerged during the day and on the surface at night, but the crossing of the strait, in order to avoid the passage by diving in the area of greatest traffic, where the currents are strongest, took place on the surface (from 60 miles east of Gibraltar to 80 miles west of the same city) instead of – as it would be done in wartime – submerged, thus nullifying part of the experience.

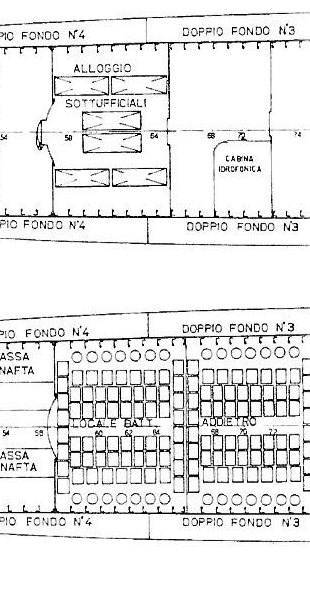

The mines holds of the Atropos (other sources identify this photo as depicting the Foca)

(from www.modelshipworld.com)

Summer 1939

Following the establishment of the Submarine Squadron Command, Atropo, Foca and Zoea formed the XLIX (or XLVIII) Submarine Squadron. Subsequently, the Foca was transferred to another squadron.

June 10th, 1940

When Italy entered the war, the Atropo, along with the twin boat the Zoea and the older Filippo Corridoni, formed the XLIX Submarine Squadron of the IV Grupsom, based in Taranto.

June 22nd, 1940

Under the command of Commander Luigi Caneschi (39 years old, from Naples), the Atropo departed for Leros on a mission to transport materials. It was its first war patrol.

June 26th, 1940

During the return navigation to Taranto, at 2.45 AM the Atropo sighted an enemy submarine east of the island of Amorgos (TN easternmost island of the Cyclades island, Greece). The Atropo attacked it with two torpedoes, but to no avail.

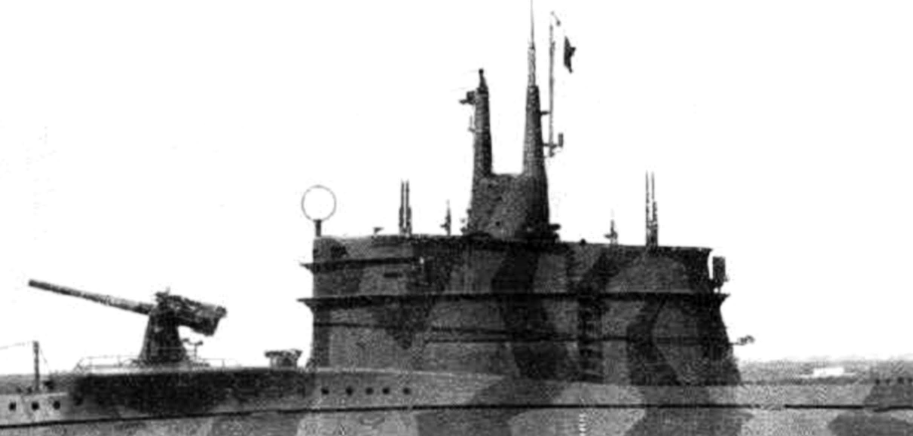

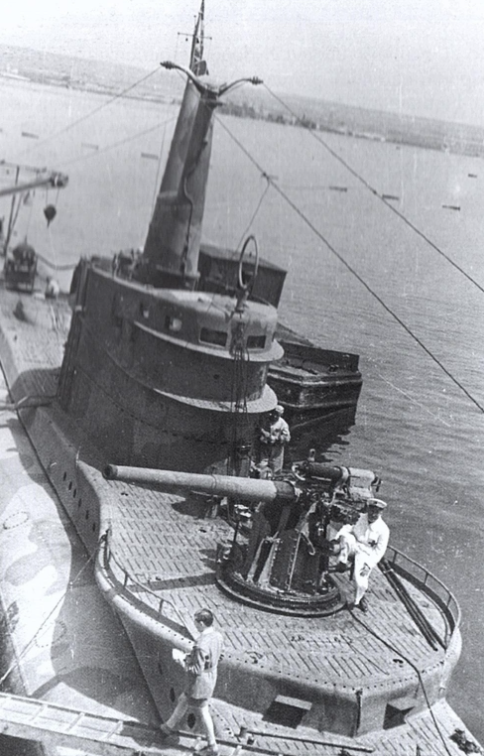

The OTO mod. 1927 100/43 mm deck gun of the Atropos, in its unusual original position, mounted on a turntable on the aft part of the conning tower, in the autumn of 1940

(From the Magazine Storia Militare)

October 27th through 30th, 1940

The Atropo carried out a patrol in the Otranto Channel, to protect convoys between Italy and Albania.

October 29th, 1940

During the night, the Atropo (Lieutenant Commander Peppino Manca) laid a minefield southeast of Zakynthos (TN Zante, Greece), in the stretch of water between this island and the mainland. The laying plan called for the submarine to lay five groups of mines, but after having laid sixteen mines, the Atropo stopped following the premature explosion of two of the ordnance, thus returning to base.

This incident, along with a similar one that had occurred four months earlier to the Zoea and also the concurrent disappearance of the Foca (which had left on October 8th to lay a minefield off the coast of Palestine and vanished without a trace), which is presumed to have been caused by the accidental explosion of the mines it was laying, lead to the decision to stop the covert mining operations by means of submarines because it was deemed too dangerous. Thereafter, the Atropo, Zoea and the other Italian mine-laying submarines would be used exclusively for transport assignments.

The accidents that occurred to the Atropo, Zoea and presumably the Foca would be attributed not to problems inherent in the mine-laying system of the Foca-class submarines, but to defects in the mines themselves (type T. 200/800 and P. 150/1939 PA), considered of having poor performance, and being inefficient and very dangerous.

The sub-chief Santo Rettondini recalled this episode decades later:

“Before going to Africa, the Navy used to make us lay mine barriers (…) in front of enemy ports (…) we started with the aft tubes (…) every so many seconds one went down (…) you could hear them coming off (…) the mine had a plate at the bottom, an anchor came off, and along with its line it went to anchor onto the bottom, and it was placed at 3 meters, at 4 meters (…) except that, we began… the first tube went well, then we started another… Out of nowhere, an explosion… As the mine fell, it exploded (…) we proceeded slowly (…) the mine fell off, we went on, it exploded, it didn’t harm us. We communicate the matter to Rome, and were sent back to Taranto, the mines were unloaded. (…) A rumor was heard that it had been a saboteur, that they had found him. These were the gossips. One of the submarines of our squadron – which consisted of three submarines: the Atropo, the Foca and the Zoea – the Foca never returned. Nothing happened to the other one (the Zoea), this happened to us, the Foca never came back.”

November 1940

The command of the Atropo is assumed by the Lieutenant Commander Bandino Bandini (34 years old, from Florence).

Lieutenant Commander Bandino Bandini

(from “Dizionario Biografico Uomini della Marina”)

November 11th through 12th, 1940

The Atropo was docked at the submarine quay in Mar Piccolo in Taranto (along with the Ambra, Amphitrite, Malachite, Pietro Micca, Naiade, Sirena, Ondina, Uarsciek and Zoea of the IV Grupsom – of which Atropo itseld was a member –, Dagabur, Serpente and Smeraldo of the X Grupsom, Giovanni Da Procida of the III Grupsom and Ciro Menotti of the VIII Grupsom), when the base was attacked by British torpedo bombers taking off from the British aircraft carrier H.M.S. Illustrious, which sank the battleship Conte di Cavour and seriously damage the battleships Littorio and Duilio (the so-called “Night of Taranto”).

November 19th, 1940

The 24-year-old sub-chief engine engineer Angelo De Michelis dell’Atropo, from Remanzacco, died aboard in the central Mediterranean.

November 20th, 1940

The Atropo left Taranto with supplies for the garrison of Leros.

November 21st, 1940

British codebreakers from the “ULTRA” organization intercepted and deciphered a message with which Rome informed Rhodes of the expected arrival of the Atropo at the conventional point “E” on November 27th. However, the British could not organize an interception, as they did not know the location of point “E”.

1941

Modification works: the 100/43 mm gun, placed in an unusual position in the aft part of the conning tower (to allow, theoretically, to fire even in less-than-optimal weather conditions), was removed and replaced with a 100/47 mod. OTO 1938 (with a reserve of 140 rounds), placed in a more traditional position on the main deck, forward of the conning tower.

The Atropo reconfigured with the deck gun mounted in a more traditional position.

(Photo U.S.M.M.)

May 9th, 1941

At 9.30 PM the Atropo (Lieutenant Commander Bandino Bandini) sailed from Taranto on a transport mission, with 78 (or 79) tons of ammunition on board bound for Derna.

Derna had been recently recaptured by the Italian-German forces advancing in Cyrenaica, and it was one of the closest ports to the front line. The Command of the Axis forces in North Africa has expressly requested that military supplies, and in particular ammunition, be sent by sea to anchorages as close as possible to the front line (Derna and Porto Bardia). Therefore, an intense and regular supply traffic to Derna was immediately started with the use of minelaying submarines. The only units (together with motorsailer) able to land in these small and poorly equipped ports. The convoys of merchant ships, which carry much larger quantities of supplies, were in fact forced to dock in Benghazi or Tripoli, Libya’s only real ports (there was also Tobruk, but at the time in British hands), but hundreds of kilometers away from the front line.

On submarines, ammunition was stored everywhere. Not just in the mine holds, but wherever there was space, even on berths and crew quarters, thus worsening the already spartan living conditions on board.

If the boat arrived at its destination during daylight hours, it had to settle on the bottom (around 70 meters deep) and wait for darkness to come. Once night fell, the boat would come to the surface and enter port, transferring the drums and jerry cans of gasoline onto boats that took them ashore. The Atropo was the first submarine ever to carry out a transport mission to Derna.

May 12th, 1941

The Atropo arrived in Derna at 7 PM and unloaded ammunition.

May 13th, 1941

The boat left Derna at seven o’clock to return to Taranto.

May 15th, 1941

It arrived in Taranto at 3.15 PM, after having covered 1,091 nautical miles on the surface and 42 submerged, consuming 40 tons of naphtha.

May 18, 1941

The Atropo set sail from Taranto at 6.25 AM for a new transport mission to Derna with 79 tons of ammunition on board.

May 20th, 1941

The boat arrived in Derna at 9 PM.

May 21st, 1941

After unloading the ammunition, the Atropo left Derna at 6.48 AM.

May 22nd, 1941

During the return voyage, between 8.25 AM and 7.20 PM the Atropo was subjected to intense and prolonged hunting by light surface units, which, however, caused only light damage.

This episode is remembered by Santo Rettondini as follows:

“… they used us to load cans of gasoline; tons loaded. They were placed in the mine holds, where there which were filled with gasoline. (…) and we went to Bardia and Derna (…) once, I remember that our commander delayed the dive. Because during daylight you have to try to hide, diving, because if you’re on the surface, they can see you. He wanted to go a little further and it happened that we were spotted at about five o’clock in the morning by three British destroyers. We were surprised. Crash dive, down to 80 meters deep. What happened, what didn’t happen, out of the blue it started to rise, it starts to go up, and it reaches almost 15-16 meters, then it went down, it went down, one didn’t know how to stop it… because he had picked up a bit of speed, going down, one had to be careful because when you go down you have to maintain a certain balance… At one point, we went down again, almost to 100 meters, it was starting to drip water… The destroyers arrived above and started with depth charges. I won’t tell you what happened inside, we were all [incomprehensible] because it was the first time that a bombing with deep mines [sic] had happened. It looked like they were bursting up in the mountains, from the explosion they had. And all close together, eh, all close, there were light bulbs that were almost going out, from the flickering that these mines made. Damage from having to climb? No.

A little water was beginning to come in. This bombardment was very long, it started in the morning, until one o’clock in the morning. There were three of them, and they kept dropping depth charges. It was like a dog and a cat, a mouse and a cat, it was like that. Because they heard us, and we heard them. When they stopped, we stopped, so as not to be heard. But they had an advantage: that as the submarine moved, they did together, in three, one moved in one direction, and they made the angle, the rest of us down there felt [that] one coming from here, the other coming from there, instead of running away we went towards them, that was the trick: take the midpoint of where they came, so that we could pass them [before] they launched the depth charges. And in fact, with this trick, we had a chief engineer and a commander who were good because they said, “Let’s take a risk. Here we all lose our skin, we go over 100 meters”.

We went to 110 meters; the submarine was tested for 100. We went over the hundred meters, that they (TN the British) knew – they told us later – that depth charges were set at 25, 50, 75 and 100 meters. They were fishing, weren’t they? One exploded at a certain height, another at a certain height, so that we could be hit at whatever depth the submarine was. Instead, they never hit the submarine. Always close, always on this side, always on the other side, never hit. Until noon, half past noon, one o’clock, the bombs were all nearby, we were not able to get away. We were like a mouse, lying down, all standing still with the watertight doors closed, all closed, all still. And for the buoyancy of the submarine, instead of the pumps, we used compressed air. This was a detail so as not to be heard (…) To be silent.

You couldn’t even speak, so as not to be heard. After half past one, two o’clock, we began to breathe a little more, because the bombs began to fall a little farther away. Towards evening farther away, farther away, at ten o’clock in the evening, farther and farther, until midnight when they were almost no longer heard, they may have stopped chasing us, because they might have dropped all the bombs. At one o’clock in the morning the commander decides to go up, give air, come to the surface. We had been without food since the day before because we were all day under bombardment, (…) slowly we tried to come to periscope depth, to look out and see if there were any planes, if there was anything nearby that prevented us from going out. They saw that there was no one there, and slowly we got out, but with difficulty, because during all this long dive to a depth of a hundred and more meters, the submarine at taken a certain crushing, its size was reduced, and it could not rise, because during the day so much water had entered from various leaks, that we had to go to the pumps to send out all the water that had come in, so that we could lighten it more and come out. The fact is that little by little we managed to open the first hutch of the conning tower, and one could immediately feel the air different from what was inside because we couldn’t breathe anymore because there was no more oxygen. We did the test of lighting a candle, it didn’t light up, it sparked and that was it because there was no more oxygen. (…) In short, we were at the limit, that’s it.”

May 24th, 1941

The Atropo arrived in Taranto at 1.20, after having covered 1,063 miles on the surface and 92 underwater. (According to a German document, the Atropo carried 59.4, 56.8, and 57 tons of fuel respectively on its three May missions.)

For the cycle of transport missions in May 1941, Commander Bandini was awarded the Bronze Medal for Military Valor, with the motivation “Commander of a submarine, destined for a supply mission, without stopping in hard fatigue, he took his unit several times to the difficult goal, countering the enemy offensive and the frequent inclemency of the weather. He showed enthusiastic dedication to service and serene courage in these missions which, with the help he brought, contributed to the success of the other Armed Forces.”

June 1st, 1941

The third-class chief helmsman Giovanni Panichi dell’Atropo, 28 years old, from Perugia, dies in the metropolitan area.

June 5th, 1941

The Atropo set sail from Taranto at 5.35 AM with 40 tons of ammunition on board to be transported to Derna.

June 7th, 1941

The boat reaches Derna at 8.10 PM.

June 8th, 1941

Once the cargo was unloaded, the boat left Derna for Taranto at 00.12 (or 5.35) AM.

June 10th, 1941

The Atropo arrived in Taranto at eleven o’clock, after having covered 1,119 miles on the surface and 32.9 submerged.

June 13th, 1941

The boat sailed from Taranto to Derna at 10:20 AM, carrying 68 tons of ammunition.

June 15th, 1941

The Atropo arrived in Derna at 9.31 PM.

June 16th, 1941

The boat left Derna at 3.20 AM.

June 19th, 1941

The boat reached Taranto at 11.10 AM, after having covered 1,050 miles on the surface and 116 submerged.

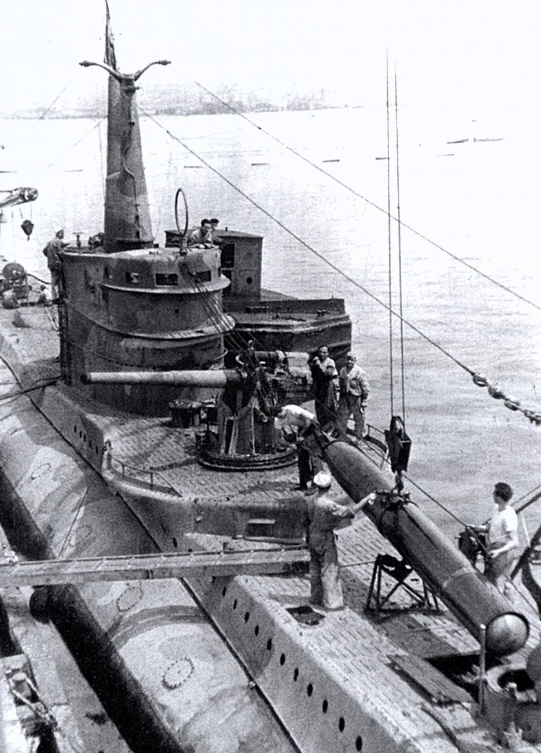

The loading of a 533 mm torpedo on the Atropo t(Taranto, in 1941).

The weapon is of the training type, without a warhead

9From the Magazine Storia Militare)

June 25th, 1941

Now under the command of Lieutenant Commander Guido D’Alterio, the Atropo left Taranto for Derna at 9.30 AM, carrying 40 tons of ammunition.

June 27th, 1941

The boat arrived in Derna at 9 PM.

June 28th, 1941

The Atropo departed Derna at 2 AM (or 1.50 AM).

July 1, 1941

The boat arrived in Taranto at eleven o’clock, after having covered 1,072 miles on the surface and 70 submerged.

July 21st, 1941

The boat departed Taranto for Derna at 10.40 AM, carrying 47 tons of ammunition.

July 23rd, 1941

The boat arrived in Derna at 11.30pm.

July 25th, 1941

The Atropo, having unloaded the cargo, left Derna at three o’clock in the morning (or 3.05 AM).

July 27, 1941

The boat arrived in Taranto at 12.45 PM, after having covered 1,038 miles on the surface and 125 submerged.

Meanwhile (on July 6th, 1941) Admiral Eberhard Weichold, liaison officer of the Kriegsmarine in Italy, wrote a letter to his Italian colleagues in which – expressing great satisfaction on the part of the Afrika Korps and the Quartermaster General of the German Army for the transport missions already carried out by Atropo and Zoea, which with their somewhat small quantities of materials brought to Derna allowed a considerable lightening of supplies to the front, since the road from Derna was much shorter than then one from Benghazi and Tripoli – proposed, among other things, the intensification of the traffic of transport submarines with the use of additional units in this task, and also advocated the use of Porto Bardia for the unloading of supplies, since this harbor is even closer than Derna to the front line.

Porto Bardia was a poorly equipped and poorly defended marina, and its utilization was full of problems and unknowns; nevertheless, Supermarina agreed to use it as a landing for some transport missions carried out by submarines.

August 12th, 1941

Under the command of Lieutenant Libero Sauro, the Atropo departed Taranto for Bardia at 12.30 PM, carrying 44,138 tons of gasoline (or diesel) in 3044 cans.

August 16th, 1941

The boat reached Porto Bardia at 4.55 PM (or 10 PM).

August 17th, 1941

It left Porto Bardia at 2.40 AM.

August 20th, 1941

The boat reached Taranto at 3.20 PM.

The performance of this mission (and of the almost simultaneous ones of the Zoea and the Corridoni) is described by Supermarina memo no. 141 of August 27th as follows:

“The units have carried out their task with considerable skill, managing to brilliantly overcome the difficulties and risks inherent in the operation. Navigation was conducted on the surface until one day before the arrival and continued submerged during the daylight hours of the day of the arrival in order to avoid being sighted by the enemy. Entry into Bardia was generally made after sunset, due to the danger presented by air attacks on the locality, which were always frequent and strong. Entering the port in such conditions presents some navigational difficulties due to the lack of light signals and the configuration of the coast which does not offer special characteristics for recognition.

In the port, the unloading operations, carried out during the night by means of rafts and rubber floats provided by the German army, lasted an average of 4 hours, and were carried out by the ship’s personnel with the cooperation of German soldiers. It should be noted that, in the event of aerial bombardment during unloading operations, the unit could not dive as the hatches were open for the unloading of the material and it was surrounded by numerous barges (up to 6 at a time) loaded with exceptionally flammable material and without any effective fire-fighting means. In addition, a possible maneuver to leave port was long and laborious given the narrowness of the stretch of water. All these difficulties were brilliantly overcome by the commanders and crews of the submarines, who noted with deep pride the satisfaction expressed to them by the German Command of Bardia for the transport of essential material to the expeditionary corps for the conduct of war operations.”

October 17th, 1941

The Atropo (Lieutenant Libero Sauro) departed Taranto for Bardia at 12.30 PM, carrying 57 tons of gasoline in cans.

October 19th, 1941

At 9.00 AM the Atropo suffered its first aerial attack, with bomb dropping and strafing, which it managed to survive unscathed. At 12.30 PM it was attacked again by another aircraft, which it also managed to repel and caused damage with the anti-aircraft guns. (Another source speaks of a single air attack, which took place in the morning, by a British Bristol Blenheim bomber, which strafed it and dropped several bombs on the boat without success, while the Atropo managed to hit it repeatedly with the fire of its machine guns, damaging it and forcing it to retreat, and then disengaged diving).

October 22nd, 1941

It arrived in Bardia at 2.30 AM, unloaded the cargo and then left at seven o’clock to return to Taranto.

October 26th, 1941

The Atropo arrived in Taranto at 1 PM.

November 13th, 1941

At a particularly critical moment in the convoy war – a few days earlier the large convoy “Duisburg”, with 34,000 tons of supplies (half of them fuel), had been completely destroyed by the British Force K – the Atropo, along with other submarines, was included in an emergency program for transporting urgent supplies to Libya by warships. Prepared by Supermarina following pressure from Germany and the Italian Army. The submarines would transport supplies to Derna and Bardia. Supermarina had already objected in the past to those two ports because they were poorly equipped and therefore had a very modest unloading capacity, but the German Commands insisted that the materials be delivered there, since these ports were much closer to the front line than the larger and better equipped port of Benghazi.

November 16th, 1941

At four o’clock in the morning, while sailing to Bardia in rough seas, the two aft batteries suddenly exploded: two men were killed, others were seriously injured. The submarine suffered serious damage, and it was difficult to avert the danger of a fire which, given the nature of the cargo, would have had a catastrophic result.

The victims were the motor sailor Domenico Albanese, 20 years old, from Reggio Calabria, and the chief helmsman third class Giovanni Bagnaschino, 29 years old.

The NCO quarters and the batteries hold where the explosion took place.

Not being in conditions to continue the mission (also due to the state of the sea), the Atropo set course for Navarino. By order of Supermarina, the destroyer Giovanni Da Verrazzano left Benghazi in the evening to rescue the submarine (which will have to be escorted for the final stretch of the navigation, starting at 5 PM on the 17th), whose intervention, however, would be completely superfluous, as the Atropo arrived in Navarino before being reached by the Da Verrazzano.

Having managed to restart the diesel engines, which had stopped after the explosion, the chief engineer of the Atropo, Lieutenant of the Naval Engineers Rinaldo Rinaldi (30 years old, from Sedegliano), was decorated with the Bronze Medal for Military Valor, with the motivation “Head of the Naval Engineering Service of a submarine on a war mission, there was an explosion in the batteries hold that caused the stopping of the motors. He directed and personally carried out the operations aimed at ensuring the start-up of the combustion engines, remaining in a dark and gas-impregnated environment. Despite the adverse sea conditions, he restored the main security services, making a valuable contribution to the ship’s rescue with a serene spirit and a spirit of sacrifice.”

A similar decoration would be conferred on Commander Sauro, with the motivation “Commander of a submarine on a war mission, after an explosion occurred in the accumulator batteries with consequent shutdown of the motors, he organized with serene courage and high competence the operations to restore the efficiency of the unit, made difficult due to the adverse sea conditions. With an unyielding will, he boldly overcame the precariousness of the situation and returned to base, giving proof of elite military virtues.”

November 17th, 1941

The Atropo arrived in Navarino (TN Greece) at 5.30 PM, stopping there for two days.

November 19th, 1941

The boat left Navarino at 1 PM to return to Taranto.

November 20th, 1941

The Atropo arrived in Taranto at 2.30 pm.

The entire episode is recalled by the deputy chief engine engineer Santo Rettondini:

“This explosion took place because of the strong sea present, there was such a strong sea (…) because we had just left Taranto, we were loaded, we were sailing on the surface, it was just passed two o’clock. I was on duty at two o’clock in the morning, and I had just started my shift. My comrade, who had gone to sleep in the non-commissioned officers’ room because there was no room there, was left dead, because the explosion took place right there.

The batteries that supplied the power to the whole submarine exploded, they were big batteries, there was a hold full of them (…) under the non-commissioned officers’ square, there was this hold full of electric accumulators. With the slamming of the sea, (…) there was a leak from some battery, a sulfuric acid leak, and it created gas into this chamber. This chamber has swelled so much, an enormous pressure, that the floor, usually flat, had developed a curve like this, it has swelled. What happened? The hatch had handles, it was closed, the bending, rising, let the latches came out, (…) and exploded. Then, when the top had curved, the pegs that were closed came out, and an explosion followed, it made a mess, all the wooden walls of the non-commissioned officers’ quarters, the bunks, were made into a pile of rubble.

And [there were] two dead and 4-5 injured. (…) I was at the stern (…) I had just taken up my duties, I was in charge of the left-hand engine, the other, on the right, there was a NCO, the chief engineer was in charge. As usual, there was a lot of noise (…) a huge noise, and the air only came out of the conning tower hatch, because the others were closed. (…) Out of the blue… It was instantaneous, an explosion, coals, dust, gases come to your face, everything comes to your face. “What happened? Was the submarine hit somewhere, help. Not here, because we are alive.” Somewhere, being eighty meters long, perhaps somewhere it took a mine, a torpedo, I don’t know, something happened.

So, the first thing you do is close the exhaust manifolds, because you have to close those, otherwise water gets in… But some of the crew, both a non-commissioned officer and the electric motorist, slipped up the hatch to open it at the back, to get out, didn’t they? And there is an opening where you cannot pass two at a time, one behind the other yes, together it is difficult. The conning tower was already full. And that was when I thought: here the engines go, in speed it goes down faster, you don’t have time to get out. And so, I stopped the engine and tried to escape too, but I couldn’t escape, because the exit from conning tower was full, and they weren’t able to open the hatch. There was a flywheel, and they couldn’t turn it. And I said, “But it’s not possible that you can’t open it, open this thing…”, but we were already in the dark by then, we were all scared. (…) I went down in the boat again. I had the handwheel to get the diesel engine going, I had a key made like this, I took the flyer and opened it. I took the key and pass it to the first one there, he managed to open it, he succeeded, he opened it and then we began to go out. As one came out, there was a rough sea. The crew had to attach themselves to the metal line that was there – from the hatch to the conning tower, there was a steel cable that they could attach to, to go to the conning tower (…) and we got out of there, with the conviction, who knows what will happen. We were at the mercy of the waves by then, everything had stopped, there was no light. Blown up, engines stopped, we floated, at the mercy of the waves. Suddenly, I hear the motorists calling. And so, we stepped forward. They give us a mask, [saying] to get in the hull, to see if we were able to restart the engines; Because nothing serious happened, enough to sink [the submarine], but this explosion had happened. So, to go to the engine room, you had to go through the maneuver room, you would came down, then move to the non-commissioned officers’ room, which was devastated, and the air, it almost closed… the watertight door, which was open, because we were sailing, was open. And then the explosion and the displacement of the air almost closed the door, almost the whole door. And then we had to move all the stuff, always in the dark. And then I made a small gap, and I managed to get through.

And when I lay down to lay my hand, I don’t see that I really put my hand on the leg of a person who was there! There’s someone underneath, dead now! And so, I managed to get through, I went inside the engine room, and slowly, always – they gave us a small flashlight, in our hands, so we could at least see where you put your feet – and then we tried to get these engines going. You had to go after the engines and bleed them, if water got in, make it go away! And so, I did that job there, of my engine, I can get it going. Like I put it to go… It sucked up all the smoke that was in it, all the dust that was in it, it sucked it all up. And you could feel the fresh air coming down from above. At that moment there was our salvation because we managed to get at least one [engine] to move (…) we managed to put only one engine to go.

The other one, we couldn’t get it going. Then, all at their posts, navigation began, the day began, with the hope that they would not see us. A good wish, because there was bad weather, it was raining, it was windy, and that helped us. (…) we went as far as Navarino (…) always with only one engine, we did 4-5 miles [knots], because only one was bad. (…) Meanwhile, during the day, they put everything in place, they tried to recover the two who had died there, the wounded began to be treated. And when we arrived at this port of Navarino, they decided to disembark and have the funeral of the two fallen. At that time there was a section of soldiers on the ground (…) and they organized the funeral with the village’s priest and place them in his cemetery. And then the rest of us marched with the priest, with these two dead, we put them to rest in this cemetery, waiting for something to be decided in Rome.

And in fact, after two days, they sent an escort destroyer to take us to Taranto to drydock. Not just because of the batteries, but because you couldn’t dive anymore, you couldn’t dive at all because we were devastated inside. Where there used to be the non-commissioned officers’ quarters, there were also pumps for the service of the various mechanisms, they were called “Calzoni” pumps, which were used by pressure to open the doors of the mines hold, torpedoes tubes, all these activities of submarine movements, of the famous rudders, both horizontal and directional, they were all moved by these machines (…) And then, since the submarine was in this state and could do nothing more, they sent us this escort. We went to Taranto, to the basin, and there they did all the repairs, everything was new. In the meantime, while they were doing these repairs, they gave the whole crew a fortnight’s premium leave in a hotel in Merano, Albergo Italia. Fifteen days, first one part [of the crew] and then the other. Fifteen days of premium leave.”

Mid-June 1942

The Atropo was sent to lie in wait off Malta during the Battle of Mid-June, in which it was not involved.

Atropo in Taranto, 1942

(From the Magazine Storia Militare)

A total of 16 boats are deployed in the central and central-western Mediterranean to counter “Operation Harpoon”. The doctrine of the use of submarines had changed compared to before: now it was planned to use submarines en masse against ships or groups of ships sighted and reported by aircraft. While in mid-August, two months later, this tactic was very successful, in mid-June the submarines did not reap any results.

June 1942

Following insistent requests from the German Commands, on June 21st the Grupsom Taranto received orders to use some of its units to transport aviation gasoline for the Luftwaffe. The German authorities were pressing for the use of submarines in transport missions to bring supplies close to the front lines, during the advance of Rommel’s forces which has just recaptured Tobruk and was advancing towards the Egyptian border. All this even though normal traffic of merchant ships was going smoothly, with very limited losses, and despite the fact that a submarine cannot carry even a tenth of what a small merchant ship can cargo. Other German agencies and commands made similar requests, but the order remains strictly limited to aircraft gasoline only.

The Atropo was among the submarines chosen for this service, along with her sister ship Zoea, the minelayers Micca, Corridoni and Bragadin and the large and elderly Enrico Toti, Antonio Sciesa, Narvalo and Santorre Santarosa.

As complained by Supermarina, the use of submarines to transport fuel to North Africa was not very convenient: a Foca-class minelaying submarine, for example, consumes 57 tons of diesel to transport 60 tons of gasoline from Naples to Tobruk.

June 23rd, 1942

The Atropo departed Taranto for Derna at 11.30 AM, carrying 56 tons of gasoline in cans.

June 26, 1942

The boat arrived in Derna at 8.15 PM.

June 27th, 1942

It left Derna at two o’clock in the morning.

June 30th, 1942

The Atropo arrived in Taranto at 12.05 PM.

July 6th, 1942

The Atropo set sail from Taranto at noon, carrying 50 tons of aviation gasoline and one and a half tons of ammunition, to be transported partly to Tobruk and partly to Derna.

July 8th, 1942

The boat arrived in Ras Hilal at 8.40 PM, staying there until the next morning.

July 9TH, 1942

It left Ras Hilal at 7:30 AM for Derna, where he arrived at 8:15 PM

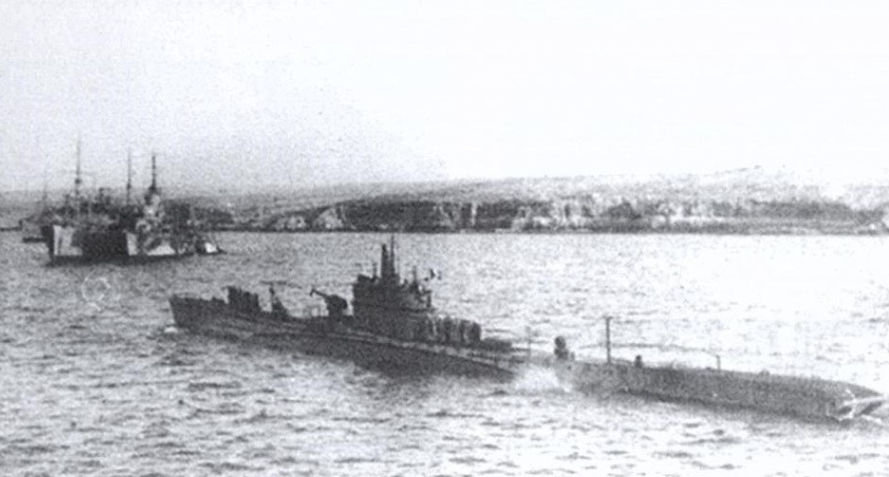

The Atrlopo (right) in Ras Hilal on July 10th, 1942, along with the Enrico Toti and Santorre Santarosa

(From the Magazine Storia Militare)

July 11, 1942

Having disembarked part of the cargo, it left Derna at 8.15 PM.

July 13th, 1942

It arrived in Tobruk at nine o’clock in the morning and delivered the remaining part of the cargo. Then, left at 6 PM to return to Taranto, along with the submarine Narvalo, also returning from a transport mission.

July 16th, 1942

It arrived in Taranto at eleven o’clock in the morning.

The Atropo in Tobruk, 1942

(From the Magazine Storia Militare)

July 21st, 1942

It left Taranto at noon, carrying 54 tons of gasoline (50 tons in bulk, four tons in cans) to be taken partly to Derna and partly to Ras Hilal.

July 23rd, 1942

It arrived in Derna at 12 PM, disembarking part of the cargo there.

July 25th, 1942

It arrived in Ras Hilal at 8 PM and delivered the rest of the cargo, and then left immediately for Taranto.

July 26th, 1942

The Atropo stopped in Benghazi from midnight to nine in the morning.

July 28th, 1942

It arrived in Taranto at ten o’clock.

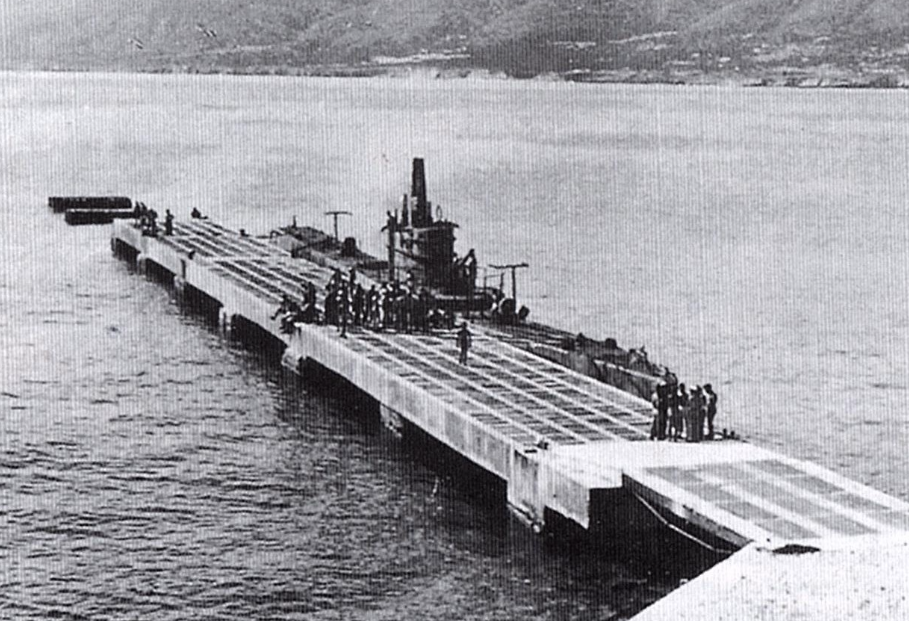

The Atropo unloading drums and jerry cans of gasoline at Ras Hilal, in 1942

(from “Uomini sul fondo. Storia del sommergibilismo italiano dalle origini ad oggi” dby Giorgio Giorgerini)

August 12th, 1942

The boat left leaves for Tripoli at 7 PM, carrying 52 tons of gasoline in cans.

August 15th, 1942

It reached Tripoli at 9.50 AM, unloaded the cargo and departed again at 4 PM

August 18th, 1942

It arrived in Taranto at 3.30 PM

September 1st, 1942

It left Taranto for Benghazi at 5:30 PM, carrying 67.5 tons of ammunition and 10 tons of food.

September 4th, 1942

It arrived in Benghazi at 7.45 am, unloaded the cargo and left again at 4.10 pm.

September 7th, 1942

The Atropo arrived in Taranto at 11.30 AM.

September 15th, 1942

It left Taranto for Benghazi at noon, carrying 65 tons of ammunition and 1.5 tons of food.

September 18th, 1942

It arrived in Benghazi at eight o’clock.

September 19th, 1942

It left Benghazi at 7 PM.

September 22nd, 1942

It arrived in Taranto at 10.50 AM.

October 9th, 1942

The Atropo departed Taranto for Benghazi at 12:30 PM, carrying 39 tons of supplies.

October 12th, 1942

It arrived in Benghazi at 8.20 AM, unloaded the food and left at 4.30 PM to return to Taranto.

October 15th, 1942

It arrived in Taranto at 4 PM.

November 10th, 1942

At 12.10 PM, the Atropo sailed from Taranto for Tripoli, carrying 50 tons of spare parts and artillery material.

November 13th, 1942

The boat arrived in Tripoli at 7.45 AM.

November 14th, 1942

After disembarking the supplies, the Atropo left Tripoli at 3.25 PM.

November 17th, 1942

It reached Taranto at 3.20 PM.

June 1943

Command of the Atropo was assumed by Lieutenant Commander Rino Erler.

June 1943

It transported a cargo of supplies to the island of Lampedusa, subjected to a naval blockade by the Anglo-American forces, who would conquer it a few days later (June 12th, 1943) after heavy bombardment. This mission of the Atropo, along with the one carried out at the same time by the smaller submarine Sirena, also destined for Lampedusa (in total, the two submarines landed 49.6 tons of supplies on the island), constituted the last transport mission carried out by an Italian submarine before the Armistice.

September 8, 1943

At the time of the proclamation of the armistice of Cassibile, the Atropo was in port in Taranto (according to another source, it would have reached Taranto following the armistice).

From the memoirs of Santo Rettondini:

“On September 8th we were in Taranto, in the port of Taranto. We were already safe in Taranto because we were in port. (…) we were in the Navy arsenal, in port. There was located the admiral in charge. We were all under Admiralty. And we were there waiting for orders; Orders dind’t come, and we’re there. So was that the troops, from Sicily, landed on our area and the British arrived first in Taranto. And we we transferred (…) under the new government, that of southern Italy (…) with Badoglio.”

September 12th, 1943

The Atropo left Taranto at 9.55 AM along with the submarines Fratelli Bandiera and Jalea to move to Malta, as per the armistice provisions. The group was accompanied by the destroyer Augusto Riboty.

September 13th, 1943

The boat arrived in Malta at 8.35 PM, along with the Jalea, Fratelli Bandiera and Riboty. The four vessels, together with the torpedo boats Libra and Orione, the seaplane carrier Giuseppe Miraglia and the submarine Ciro Menotti, went to moor in St. Paul’s Bay.

September 21st, 1943

The Italian submarines in Malta, previously scattered in the various moorings of the island, were grouped into two groups, one concentrated in Marsa Scirocco and the other in São Paulo.

The Atropo was temporarily stationed in the mooring of Marsa Scirocco, together with nine other submarines (Axum, Bandiera, Bragadin, Corridoni, Giada, Marea, Nichelio, Settembrini, Vortex; from October 6th also the Turchese), under the “dependence” of the battleship Giulio Cesare.

October 16th, 1943

Following Italy’s declaration of war on Germany, the Atropo left Malta at 8.30 AM along with the submarines Zoea, Corridoni and Ciro Menotti, bound for Haifa (Palestine). (According to the war diary of the British Levant Command, these submarines were sent to Haifa from Taranto, but a mistake seems likely.)

The Atropo (second boat from the left in the front row) and other Italian submarines moored at Sliema Creek (Marsa Muscetto, Malta) in September 1943

(Imperial War Museum)

Since the Italian garrisons of some of the Dodecanese islands were still resisting German attacks, these submarines were sent to Haifa to be employed in missions to supply arms and ammunition to those islands (as well as to evacuate wounded on the way back), especially Leros. Their estimated carrying capacity was 70 tons of ammunition or 40 tons of food.

The refueling of Leros took place under particularly difficult conditions: German air supremacy was such that the units carrying supplies could only move at night, and they had to ensure that they are outside of the Luftwaffe’s range by dawn. Unable to use merchant ships, everything had to be transported by destroyers, caiques, smaller boats. Several units fell victim to German air attacks. Not even an airlift was conceivable, as few transport aircraft were available. In view of the situation, submarines seem to be the most appropriate means of transporting to supplies Leros in conditions of reasonable safety. In addition to the Italian boats, the British submarines Severn and Rorqual were also used to supply Leros. The use of the six submarines to supply Leros was authorized during a meeting of the Commanders-in-Chief of the Allied Forces in the Middle East, in the presence of the First Sea Lord and the Foreign Secretary of the United Kingdom; the request to the Command of the Regia Marina to make submarines available for transport missions was made by the Allies on October 13th.

October 20th, 1943

The Atropo reached Haifa at 8.55 am, one day ahead of Zoea, Menotti and Corridoni.

Here the Italian Higher Naval Command of the Levant (Maricosulev Haifa) was established, with a Submarine Group of the Levant (Grupsom Levante), under the command of Commander Carlo Liannazza. The Group’s submarines were under the command of the Royal Navy’s 1st Submarine Flotilla. Their operations were coordinated with the Senior Submarine Officer Levant Area, Haifa, which issued the operation orders for individual missions. According to the book “Spoils of War: The Fate of Enemy Fleets after the Two World Wars” by Aidan Dodson, during its period of operation in waters under British jurisdiction the Atropo received the temporary “pennant” N31.

Beginning on October 26th, the four Italian submarines departed Haifa at regular intervals, carrying 45 tons of supplies on each trip. All journeys come to a happy ending.

October 26th, 1943

At 11:15 PM, the Atropo (Lieutenant Aredio Galzigna) left Haifa for Leros with a cargo of supplies.

October 30th, 1943

It arrived in Leros at 9 PM.

October 31st, 1943

After unloading the supplies, it left Leros at 3.30 am.

November 3rd, 1943

It arrived in Haifa at 6:55 pm.

Regarding the use of submarines to supply Leros, the official narration of the U.S.M.M. (TN Historical Bureau Italian Navy) writes: “The actual contribution of the submarines to suppling (Lers) were of course not of great importance, given their natural poor carrying capacity. They brought ammunition, gasoline, various materials, and even Bofors guns on deck. On the other hand, the moral contribution that the nocturnal visits of the Italians submarines gave the defenders of Leros for the satisfaction and prestige that they derived from this Italian military activity. In fact, it was carried out without any particular British control (except for a representative of the Allies for the communications service), despite the fact that the submarines were if full war asset and ready to fight during the crossing, which was, for the most part, carried out under covert navigation.” Unloading operations must be carried out at night, because it is only in the dark that the Luftwaffe suspends its continuous air attacks.

November 16th, 1943

At one o’clock in the morning, the Atropo departed Haifa (for another source, Beirut) with a cargo of supplies for the garrison of Leros.

November 17th, 1943

At 6:12 PM, after 36 hours at sea, the Atropo received orders to return to Haifa (according to another source, Beirut): Leros had fallen.

November 19th, 1943

The Atropo arrived in Haifa at 7.05am.

November 22nd, 1943

It left Haifa at 10.10 AM with a load of supplies for Castelrosso, still in Italian-British hands.

November 25th, 1943

It arrived in Castelrosso at 8.55 AM, but did not unload the supplies; On the other hand, the soldier Vincenzo Di Domenico, of the 16th Infantry Regiment (Division “Regina”), captured by the Germans in Leros but escaped from captivity, was embarked. The Atropo then departs for Haifa, where it arrived at 5.20 pm.

November 28th, 1943

With the German victory in the Dodecanese, the Atropo left Haifa at 6 PM to return to Taranto. (According to one source, during the stay in Haifa, the Atropo also carried out some training missions with British corvettes.)

December 3rd, 1943

The submarine arrived in Taranto at 5.10 pm. In the following months, it participated in exercises with Italian units, as well as in escort and patrol missions, with a British liaison officer on board.

May 1944

Subjected to a period of refetting in Taranto.

September 15th, 1944

The Atropo (Lieutenant Aredio Galzigna) left Taranto at 5.10 PM bound for the Atlantic, where it would be used as a target in exercises for the training of Allied anti-submarine vessels.

A total of eight Italian submarines were assigned to this task (West Atlantic Submarine Flotilla), based in Bermuda, Guantanamo Bay, Key West, Port Everglades, New London and Casco Bay, between February 1944 and the end of 1945. In addition to the Atropo, also the Vortice, Onice, Marea, Dandolo, Giovanni Da Procida, Tito Speri and Goffredo Mameli. They were part of the U.S. Navy’s Submarine Squadron 7, along with seven Free French submarines (Argo, Amazone, Antiope, Archimedes, Casabianca, Le Centaure and Le Glorieux).

September 27th, 1944

After a stopover in Augusta, the Atropo reached Gibraltar and moored at the Pigmy pier, next to the British submarine Truant.

October 7th, 1944

The boat departed Gibraltar at 10:53 AM bound for Bermuda, escorted by the U.S. destroyer Frederick C. Davis.

October 20th, 1944

Arrival in Bermuda.

November 8th 1944 through March 3rd, 1945

The Atropo participate in 48 drills between Malatar and Port St. George.

December 11th though 12th, 1944

The boat participated in an exercise with a task group consisting of the escort aircraft carrier USS Core, seven destroyer escorts, and the PCE-846 submarine destroyer.

January 2nd through 5th, 1945

The boat participate in an exercise with another task group, consisting of the escort aircraft carrier USS Bogue, the escort destroyers USS Haverfield, Swelling, Willis, Janssen, Wilhoite, and Cockrill, and the submarine destroyer PCE-846.

January 9th through 11th, 1945

Another exercise with the Bogue and the PCE-279 submarine destroyer.

February 12th though 14th, 1945

Antisubmarine exercise with the destroyer escort USS Cross and the fast transport USS Register. The Cross made eighteen passes with depth charges.

March 3rd, 1945

The Atropo left Port St. George, Bermuda, bound for Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, escorted by the newly commissioned U.S. Coast Guard frigate Racine.

March 7th, 1945

It arrived at Guantánamo Bay. In the following months, it took part in another 70 exercises in these waters.

September 24th, 1945

At the end of the Second World War, following the surrender of Japan, the Atropo and another Italian submarine, the Dandolo, left Guantanamo for Port Royal, Jamaica.

September 30th, 1945

Atropo and Dandolo arrived at Port Royal.

October 5th, 1945

At noon, Atropo, Dandolo and the Italian submarines Vortice, Onice, Marea, Giovanni Da Procida and Tito Speri set sail from Bermuda escorted by the U.S. submarine rescue ship Chain to return to Italy.

October 16th, 1945

The submarines reach Punta Delgada, in the Azores, in the morning; the exception was Atropo, which reaches São Miguel at 8.23 AM.

October 18th, 1945

At 8:14 AM, the Atropo left São Miguel, rejoining the rest of the group, which also left Punta Delgada around noon and headed for Gibraltar.

October 26th, 1945

The Atropo and the other submarines reach Gibraltar in the morning.

October 28th, 1945

The Atropo and the other submarines departed Gibraltar at about three o’clock in the morning.

November 3rd, 1945

The Atropo and the other submarines finally reach Taranto: the war is over for them too. The Atropo was laid up in Taranto.

February 10th, 1947

The Atropo was included in the “List of ships that Italy will have to place at the disposal of the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom, the United States of America and France” by the provisions of the peace treaty signed in Paris. More precisely, the Atropo was assigned to the United Kingdom, along with the submarine Alagi, the battleship Vittorio Veneto and some motor torpedo boats, as reparation for war damages.

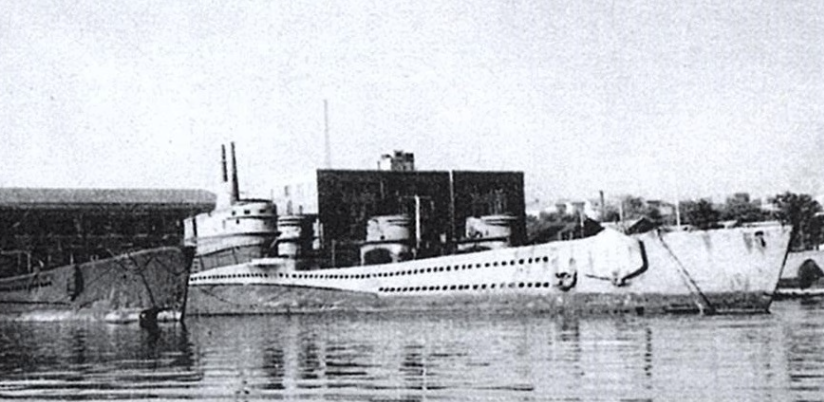

The Atropo in Taranto, 1947

(From the Magazine Storia Militare)

The British, not needing new units in addition to those mass-produced under the war construction programs (they have, in fact, more than were needed in peacetime), renounce delivery, but demand that the units destined to them be immediately scrapped.

February 1st, 1948

The Atropo was removed from the roster of the navy by the provisions of the peace treaty. (According to some sources, including “The Italian Submarines 1940-1943” by Erminio Bagnasco and Maurizio Brescia, the radiation took place as early as March 23, 1947).

December 5th, 1948

The Taranto fisherman Francesco Intini gets on board the Atropo, decommissioned in Taranto and awaiting demolition, to steal some metal components; In order to conceal the theft, he voluntarily damaged some equipment and thus caused the submarine to sink, which sank slowly, within a few hours. Intini, caught in the act by the carabinieri and security guards and immediately arrested (the sinking of the Atropo took place just as the carabinieri were drawing up the arrest report), was sentenced in March 1951 to twelve months’ imprisonment for theft of scrap and for insulting a public official, while he was acquitted of the charge of culpable sinking. The wreck of the Atropo was later recovered and demolished in Taranto.

Original Italian text by Lorenzo Colombo adapted and translated by Cristiano D’Adamo

Operational Records

| Type | Patrols (Med.) | Patrols (Other) | NM Surface | NM Sub. | Days at Sea | NM/Day | Average Speed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Submarine – Medium Range | 30 | 27884 | 2703 | 171 | 178.87 | 7.45 |

Actions

| Date | Time | Captain | Area | Coordinates | Convoy | Weapon | Result | Ship | Type | Tonns | Flag |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6/26/1940 | 02:45 | C,F. Luigi Caneschi | Mediterranean | East of Amorgos | Torpedo | Failed | Unknown | Submarine | Unknown |

Crew Members Lost

| Last Name | First Name | Rank | Italian Rank | Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Albanese | Domenico | Naval Rating | Comune | 11/16/1941 |

| Bagnaschino | Giovanni | Chief 3rd Class | Capo di 3a Classe | 11/16/1941 |

| De Michelis | Angelo | Junior Chief | Sottocapo | 11/19/1940 |

| Panichi | Giovanni | Chief 3rd Class | Capo di 3a Classe | 1/6/1941 |